In June 2015 Donald Trump rode an escalator into the lobby of Trump Tower in New York City to announce his candidacy for president – an escalator ride that quickly became famous.

Politico called it “the escalator ride that changed America,” and The Guardian spoke of “the surreal day Trump kicked off his bid for president” with a “golden escalator ride.”

The escalator has long been a symbol of social mobility, of the ease with which Americans have been able to rise to the top of the social and economic hierarchy. For this reason, it has featured in a range of recent political campaigns.

For decades the escalator has been a ready symbol in debates over economic inequality and globalization. For many it captures how the economy used to work, how it no longer seems to work and how it might work again. The escalator’s political meaning has shifted over the years – but it’s never gone away, and candidates on both the right and the left love to invoke it.

Justin Trudeau’s ascension

In my work on the cultural history of the escalator, I have been struck by its persistent use in recent years.

During Justin Trudeau’s 2015 campaign to become prime minister of Canada, a television ad featured the candidate climbing an escalator the wrong way. Trudeau remains in place until he reverses the escalator’s direction and uses it to propel himself upward.

Campaign ad for Justin Trudeau: “Harder to Get Ahead”

For Trudeau’s Liberal Party, the escalator served as a metaphor for how upward mobility had languished under the Conservative government of Stephen Harper.

The ad symbolically replaced the 18th-century economist Adam Smith’s metaphor of an “invisible hand” – coined to describe the way that prices seem to rise and fall of their own accord in a capitalist economy – with an escalator. Trudeau’s liberal politics, his campaign promised, were like a “master switch” capable of redirecting the escalator’s flow.

For Trudeau’s leftist critics in the opposition New Democratic Party, though, the escalator ad symbolized everything that was wrong with Trudeau’s politics, because it asked voters to trust that globalization and corporate welfare would bring wealth and social mobility. “Stop the Escalator” became a progressive rallying cry of the 2015 campaign.

Donald Trump’s television series “The Apprentice” was likewise obsessed with the politics of social mobility. At the end of each episode, contestants were sent either “up to the suite – or down to the street.” To be important is to have access to the corporate boardroom and the penthouse.

For Trump, riding the escalator is a symbol of social mobility and power. In “The Art of the Deal,” Trump boasts about how expensive it was to install.

The fact that Trump rode down the escalator, rather than up it – as if he were condescending to come down, rather than inviting us to come up – turned the symbol on its head.

Criticism of globalization

The political right around the world has often targeted the escalator. The objection is precisely to its accessibility – that anyone can ride it.

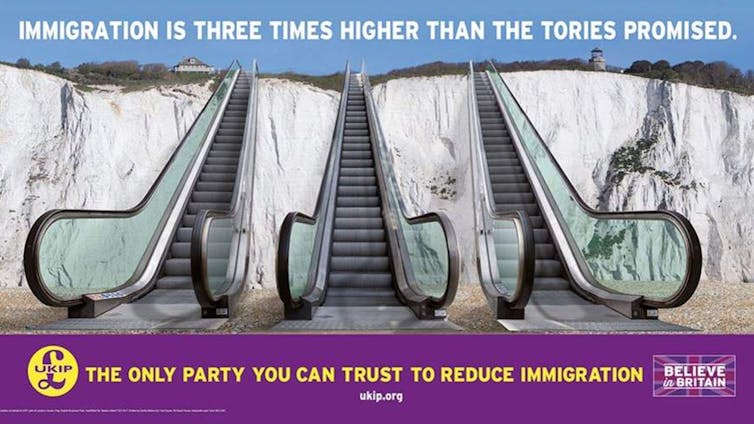

In 2014, during the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum over whether to leave the European Union, the populist U.K. Independence Party ran an advertisement depicting an escalator built over the White Cliffs of Dover. The slogan read: “No Border, No Control.”

Pro-Brexit Advertisement for the U.K. Independence Party (2014)

UKIP Escalator Advertisement (2015)

The word “control” here suggests not only an unprotected border, but a broader sense of social disorder, symbolized by the way that the escalator, a mechanical contraption, is depicted invading a pastoral landscape.

When Trump announced his presidential run after riding down the escalator into the lobby, he focused on issues of mobility and borders. He complained, infamously, that Mexico was sending America its rapists and drug dealers – that the United States had entered an era in which working-class Americans were stuck in place while migrants, terrorists and drug dealers had become mobile.

Implicitly, Trump in 2015 questioned whether America’s engine of social mobility was working for the “right” people.

Escalation versus de-escalation

The escalator has shaped political rhetoric more generally. When we refer to the way a conflict escalates, we are using a metaphor that originated with the escalator.

The term is of incredibly recent origin. It first emerged in the 1920s as a verb for riding an escalator. And it took on its present meaning only in 1959, in the context of the Cold War.

To “escalate” in the context of the Cold War was to take the conflict to the next level. It was not to commit a single act of retaliation but to initiate a new sustained level of violence. “Escalation theory” was intended to slow conflict, to avert an immediate turn toward nuclear war among the global superpowers.

Since then, however, “escalation” has mostly served to rationalize never-ending, low-level forms of conflict. Violence, in this way, is ratcheted up and down, escalated and de-escalated, but it never ceases.

Modern American politics is characterized by unending escalation. One can cite the wars in Vietnam and, now, Afghanistan. There’s the partisan rhetoric and political brinkmanship over Senate procedures and Supreme Court appointments. There’s police violence.

Much of the public debate around these issues is preoccupied with finding “de-escalation” strategies – ways to slow America’s seemingly uncontrollable cycle of conflict and violence.

Why escalators

The escalator has become such a powerful and pervasive symbol in both politics and speech perhaps precisely because it is a machine.

It operates mechanically, “on its own accord” and without human input, making it a ready symbol for undemocratic, technocratic policymaking that occurs without input from the general public.

Trudeau was unfazed by these associations. But the growing popularity of the escalator, as a symbol, on the political right reflects a growing cynicism about democratic governance.

Antonio José Seguro Poised for Landslide Win in Portugal Presidential Runoff

Antonio José Seguro Poised for Landslide Win in Portugal Presidential Runoff  Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters

Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters  U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday  Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  Ghislaine Maxwell to Invoke Fifth Amendment at House Oversight Committee Deposition

Ghislaine Maxwell to Invoke Fifth Amendment at House Oversight Committee Deposition  China Warns US Arms Sales to Taiwan Could Disrupt Trump’s Planned Visit

China Warns US Arms Sales to Taiwan Could Disrupt Trump’s Planned Visit  Trump Administration Appeals Court Order to Release Hudson Tunnel Project Funding

Trump Administration Appeals Court Order to Release Hudson Tunnel Project Funding  Taiwan Says Moving 40% of Semiconductor Production to the U.S. Is Impossible

Taiwan Says Moving 40% of Semiconductor Production to the U.S. Is Impossible  Israel Approves West Bank Measures Expanding Settler Land Access

Israel Approves West Bank Measures Expanding Settler Land Access  Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics

Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics  Trump Congratulates Japan’s First Female Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi After Historic Election Victory

Trump Congratulates Japan’s First Female Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi After Historic Election Victory  Anutin’s Bhumjaithai Party Wins Thai Election, Signals Shift Toward Political Stability

Anutin’s Bhumjaithai Party Wins Thai Election, Signals Shift Toward Political Stability  Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges

Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges  Trump Slams Super Bowl Halftime Show Featuring Bad Bunny

Trump Slams Super Bowl Halftime Show Featuring Bad Bunny  New York Legalizes Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

New York Legalizes Medical Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients  Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy

Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy