Wider availability of newer hepatitis C drugs may not only lead to fewer cases of this blood-borne disease, but may also slow the rise in related liver cancer.

But these so-called direct acting antiviral drugs have not been widely available in Australia or overseas for long enough for us to confirm this long-term trend.

So, we need to see if their increased use is linked with a downturn in new cases of liver cancer, the focus of our research.

Liver cancer rates rising

Primary liver cancer (liver cancer that starts in the liver rather than spreading from elsewhere) is the fifth most common cancer in men and the ninth in women globally. In 2012, it was responsible for 746,000 deaths around the world.

On average, people only live for a year once diagnosed. This is partly because most people are only diagnosed when the cancer is advanced and available treatments do not always prolong life.

In Australia, about 1,500 people a year are diagnosed with the most common type of primary liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and a similar number die from it each year. Both numbers have doubled over the past two decades.

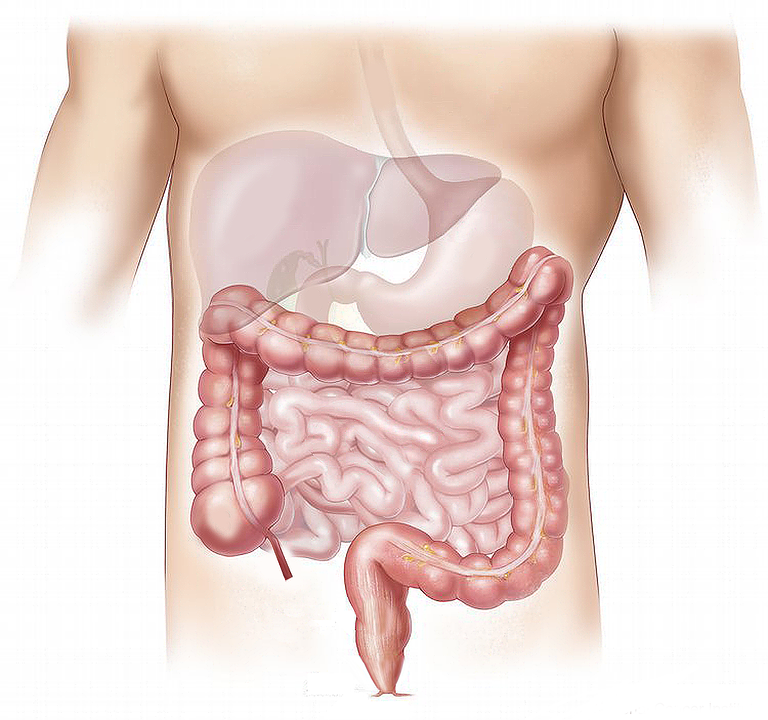

A major driver of the rise in the number of new cases of primary liver cancer and people dying from it has been infection with the hepatitis C virus. Over time, infection leads to cirrhosis of the liver, where scar tissue replaces normal, healthy tissue. This damage makes the liver prone to cancer.

Older drugs made a start

Until recently, we’ve seen an ageing population of people with chronic hepatitis C but few were treated. Between the early 2000s and mid-2010s, only 1-2% a year of the estimated 230,000 people living with chronic hepatitis C in Australia were treated each year with interferon-based therapy.

This injectable medication mimics a protein the body naturally produces to fight off infections. But few people were treated with it as the drugs weren’t always effective, had side-effects ranging from fatigue to depression and had to be taken for 24–48 weeks.

The natural history of chronic hepatitis C (cirrhosis, liver failure and primary liver cancer) and an ageing population means without major improvements in hepatitis C treatment uptake and outcomes there would be a poor outlook. We would expect to see a large burden of advanced liver disease in Australia over the next decade.

Direct-acting antivirals make a difference

Fortunately, direct-acting antiviral therapies and the move towards interferon-free oral treatments have revolutionised how we treat hepatitis C.

Direct-acting antiviral drugs work by blocking the action of specific proteins or enzymes in the hepatitis C virus, which are essential for the virus to replicate and infect liver cells.

With these drugs, hepatitis C treatment has minimal side effects, is short (8-24 weeks), and 95% of people who take the drugs are effectively cleared of the virus.

Although direct-acting antivirals have been available since 2014, they have been listed in Australia on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme since March 2016 for any adult with hepatitis C. General practitioners as well as specialists can prescribe the drugs, with no cap on numbers of people treated a year, no restrictions based on the stage of liver disease, or ongoing drug and alcohol use.

This A$1 billion hepatitis C treatment investment for the period 2016-2020 has been championed internationally as a major public health initiative.

In 2016, between March and December, more than 30,000 people in Australia started treatment, equating to 13% of the population living with chronic hepatitis C, and more than were treated in the previous decade.

Importantly, an estimated 60% of people with hepatitis C-related cirrhosis (those at highest risk of liver cancer) have received direct-acting antivirals.

This provides an opportunity to confront the rising disease burden of liver cancer in Australia.

Spotting trends

Ongoing surveillance of trends in new cases of liver cancer and deaths from it will be crucial in evaluating how close we are to ending hepatitis C-related liver cancer, and in particular hepatocellular carcinoma.

If we show treating hepatitis C reduces a person’s risk of getting liver cancer, and prolongs survival for people already with it, it would change cancer prevention and treatment policy and practice around the world.

Strategies would be developed to ensure people with hepatitis C get access to treatment, including people living with liver cancer. These potential findings would also increase efforts to ensure people with hepatitis C and serious liver disease have regular liver ultrasounds to detect early liver cancers. Increased screening would lead to a higher number of patients having their liver cancer treated.

Maryam Alavi receives funding from CASCADE International Fellowship; the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement No PCOFUND-GA-2012-600181.

Maryam Alavi receives funding from CASCADE International Fellowship; the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement No PCOFUND-GA-2012-600181.

Greg Dore is supported through a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Practitioner Fellowship. He was received research support and is a consultant for Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Janssen; has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, and Roche; is on the speaker’s bureau for Gilead Sciences, Merck, Janssen, and Roche; is a member of the advisory board for Gilead Sciences, Merck, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and Abbott Diagnostics; and has received travel support from Gilead Sciences, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, and Roche. The authors have just been granted a Cancer Council NSW Research Award to evaluate the impact of improving hepatitis C treatment on rates of liver cancer.

Vanda Pharmaceuticals Wins FDA Approval for New Motion Sickness Drug After Four Decades

Vanda Pharmaceuticals Wins FDA Approval for New Motion Sickness Drug After Four Decades  Merck Raises Growth Outlook, Targets $70 Billion Revenue From New Drugs by Mid-2030s

Merck Raises Growth Outlook, Targets $70 Billion Revenue From New Drugs by Mid-2030s  Royalty Pharma Stock Rises After Acquiring Full Evrysdi Royalty Rights from PTC Therapeutics

Royalty Pharma Stock Rises After Acquiring Full Evrysdi Royalty Rights from PTC Therapeutics  Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk Battle for India’s Fast-Growing Obesity Drug Market

Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk Battle for India’s Fast-Growing Obesity Drug Market  U.S. Vaccine Policy Shifts Under RFK Jr. Create Uncertainty for Pharma and Investors

U.S. Vaccine Policy Shifts Under RFK Jr. Create Uncertainty for Pharma and Investors  Sanofi Reports Positive Late-Stage Results for Amlitelimab in Eczema Treatment

Sanofi Reports Positive Late-Stage Results for Amlitelimab in Eczema Treatment  TrumpRx.gov Highlights GLP-1 Drug Discounts but Offers Limited Savings for Most Americans

TrumpRx.gov Highlights GLP-1 Drug Discounts but Offers Limited Savings for Most Americans  Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Cut Obesity Drug Prices in China, Boosting Access to Wegovy and Mounjaro

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Cut Obesity Drug Prices in China, Boosting Access to Wegovy and Mounjaro  Weight-Loss Drug Ads Take Over the Super Bowl as Pharma Embraces Direct-to-Consumer Marketing

Weight-Loss Drug Ads Take Over the Super Bowl as Pharma Embraces Direct-to-Consumer Marketing  Federal Appeals Court Blocks Trump-Era Hospital Drug Rebate Plan

Federal Appeals Court Blocks Trump-Era Hospital Drug Rebate Plan  Viking Therapeutics Sees Growing Strategic Interest in $150 Billion Weight-Loss Drug Market

Viking Therapeutics Sees Growing Strategic Interest in $150 Billion Weight-Loss Drug Market  California Jury Awards $40 Million in Johnson & Johnson Talc Cancer Lawsuit

California Jury Awards $40 Million in Johnson & Johnson Talc Cancer Lawsuit  Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Cut Obesity Drug Prices in China as Competition Intensifies

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Cut Obesity Drug Prices in China as Competition Intensifies