Theresa May’s successful defence of her leadership has left her weakened, particularly since she had to give an assurance that she would not stay on as leader after the negotiations with the EU are complete to convince some of her MPs to support her. Leaders who announce a sell-by date generally become lame ducks. So this raises the question: where do we go from here?

There appear to be four options open to the government to move things forward. It could try to rescue May’s deal by making it acceptable to the House of Commons or hand the issue back to the electorate in the form of a second referendum. It could go for a Norway plus agreement, which keeps the UK in the customs union and the single market. Or, May could opt for a Canada plus plus agreement – taking the UK out of both the customs union and the single market into a hard Brexit.

Labour’s preferred option of a general election is unlikely, since it requires a no-confidence vote in the House of Commons which the DUP has already ruled out.

All of the options are problematic. In the case of her deal, May has to persuade both the DUP and the Brexiters in her own party to support it. These dissenters want a legally binding agreement which removes or time limits the Irish border backstop. The problem is that the EU refuses to change the legal text agreed last year and in the present atmosphere of mistrust vague assurances from Brussels will not be enough to persuade the dissenters to accept it.

The “people’s vote” or a second referendum would require legislation and is the preferred option of Remainers although there is no guarantee that it would deliver the outcome they want. Again the dissenters will oppose this, although if everything else failed the government could get this through with the support of the opposition parties. May has vigorously opposed this up to now, but then she opposed another general election up to the point she actually called one in 2017.

The third alternative which has been floated as a possibility by work and pensions secretary Amber Rudd is a “Norway plus” deal. The two problems with this are that it leaves Britain abiding by EU rules without having any say in how they are set and that it means accepting free movement of labour from the EU. Immigration played a decisive role in explaining the vote to leave in 2016. Thus few believe that the Norway plus option is compatible with Brexit.

Canada plus plus would mean a hard Brexit and an arms-length relationship with the EU based on reducing tariffs and trade barriers and harmonising regulations. It is attractive to the Brexiters because it would keep Britain out of the single market and customs union. But many Remainers would consider it to be very similar to a no-deal Brexit. It does have the advantage, however, of being supported by the dissenters in the House of Commons – as long as the backstop is not part of the deal.

Brexit forecasts

One important argument in favour of a Canada plus plus deal is that official warnings about the disastrous effects of Brexit have proved illusory. The Treasury published a report on the short-term consequences of Brexit just prior to the referendum vote. It included forecasts of what would happen to the economy over a two-year period if Britain voted to leave. Two scenarios were examined, one described as a shock scenario and the other as a severe shock scenario. The first assumed that the effects of the Brexit vote would be rather similar in magnitude to the 1990-91 recession and the second assumed it would be 50% worse.

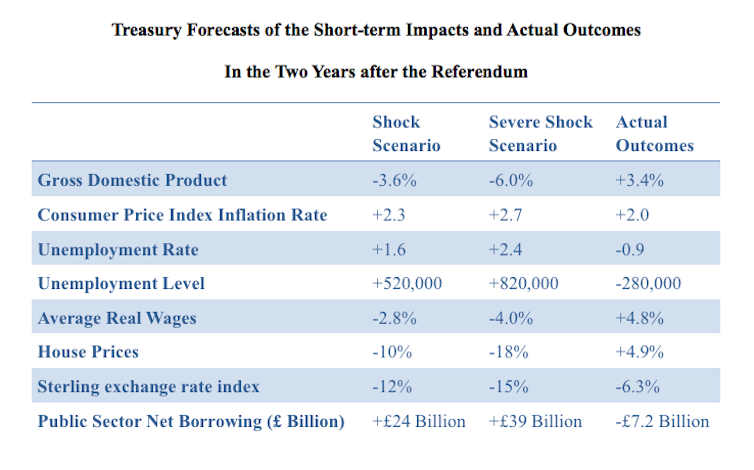

The table below shows the predictions associated with the two scenarios, and they were uniformly pessimistic, anticipating a reduction in GDP of 3.6% in the shock scenario and 6% in the severe shock scenario. They also predicted higher inflation and unemployment, declining real wages and house prices and a fall in the pound. Finally, they forecast that the public sector borrowing requirement, the difference between government income and expenditure, would increase by at least £24 billion.

The actual outcomes up to the third quarter of 2018 appear in the last column of the table, and they differ dramatically from the forecasts. In every case, they show that the forecasts were wrong by significant margins. Thus GDP rose by 3.4% rather than fell; inflation was positive but it grew at a lower rate than predicted; unemployment declined by more than a quarter of a million rather than increased; average wages and house prices rose rather than fell; the sterling exchange rate declined, but by much less than predicted; and the public sector borrowing requirement fell rather than rose.

Brexit forecasts. HM Treasury (2016) and Office of National Statistics

This forecasting failure suggests that, in the long-run, a Canada plus plus hard Brexit may make no difference to the UK economy, and this might also be true of a no-deal Brexit, even though this will undoubtedly cause short-term disruption. In our book on the referendum, we showed that joining the EU in 1973 had no impact on Britain’s long-term growth and this may be repeated when we leave. So the Canada plus plus option may be the only one to get a majority in the House of Commons, although this could become a no-deal Brexit if the EU keeps on insisting on the Irish backstop.

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary