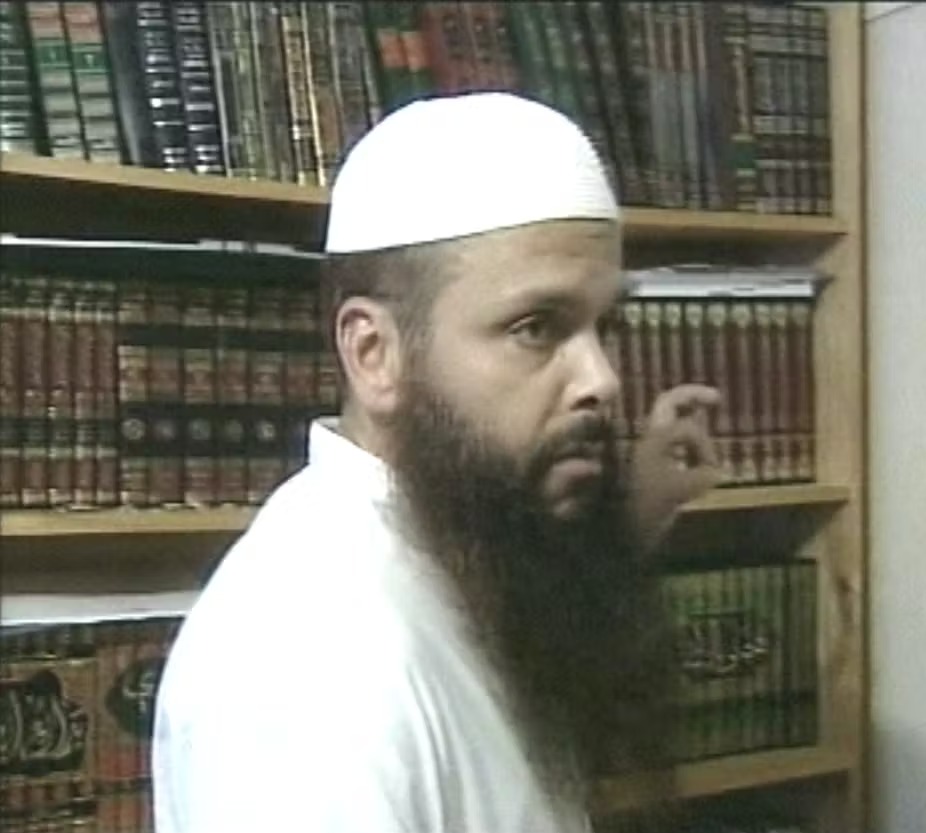

Yesterday, Abdul Nacer Benbrika, perhaps Australia’s most notorious convicted terrorist, won in the High Court.

A six-one majority of the court struck down a ministerial power to revoke the Australian citizenship of certain terrorist offenders.

Benbrika’s citizenship had been revoked as a result of his conviction in 2008 of a range of terrorism offences, including directing the activities of a terrorist organisation for which he was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Following the court’s decision, Benbrika remains an Australian citizen. So will he go free? And what does this mean for national security?

Unconstitutional punishment

This was not the first time the High Court had stopped the minister for home affairs revoking the citizenship of someone involved in terrorism.

Delil Alexander was a dual citizen of Australia (by birth) and Turkey (by descent) when he entered Syria in 2013 with the terrorist organisation ISIS.

In 2021, the minister revoked Alexander’s Australian citizenship because Alexander had engaged in certain terrorist conduct which demonstrated he had “repudiated his allegiance to Australia”.

Revoking his citizenship was, the minister reasoned, in the public interest.

At that time, Alexander was in prison in Syria and could not be contacted by his family or lawyers. His sister, Berivan, challenged the citizenship-stripping law on his behalf and won the case.

In Benbrika’s case, the situation was a little different.

Unlike Alexander, Benbrika (a dual national with Algeria) had actually been convicted of terrorism offences, which gave the minister a basis on which to strip his Australian citizenship.

Yet the court’s reasons for striking down the citizenship-stripping powers were similar in the two cases.

First, the court acknowledged that loss of one’s citizenship is at least as serious as detention.

Second, the court interpreted the law as being designed to punish the person for their conduct.

Under the separation of powers, which the Constitution protects, imposing punishments for wrongdoing is generally the work of courts and should follow a criminal trial and finding of guilt.

In this case, the minister was essentially – and unconstitutionally – trying to go around the courts by punishing these individuals outside the criminal process.

What now for Benbrika?

The consequence of Alexander remaining an Australian citizen is that it remained Australia’s responsibility to, for instance, take steps to find out where he was, re-establish contact with him, and provide consular assistance.

Alexander may even need to be brought back to Australia where he would be dealt with under our own laws and justice system (it is, after all, a serious federal offence to join ISIS).

Benbrika, on the other hand, has served his sentence for terrorism offences and won his fight to maintain his Australian citizenship.

So will he walk free? Is it only a matter of time before he is radicalising more young people and inciting further hatred and violence?

Whatever lies ahead for Benbrika, it is unlikely to be any sense of freedom.

Australia has more extensive counterterrorism law than anywhere else in the world. A recent count put the tally at almost 100 laws enacted since the 9/11 attacks in 2001.

Many of those laws tweak the usual rights given to people as they move through the criminal justice system.

This includes the option of post-sentence imprisonment – “continuing detention orders” – for those who are assessed to pose an unacceptable risk of committing national security offences.

Such an order can be made for up to three years and there are no limits on renewal.

Not only has Benbrika already been subject to those orders but, in 2021, he lodged an unsuccessful High Court challenge to those laws.

For as long as Benbrika is assessed to pose an “unacceptable risk” to the community, he will remain in prison.

But what if he satisfies a court that his release no longer poses an unacceptable risk?

Under Victorian law, Benbrika could be subject to an extended “supervision order”, which can be made for up to 15 years (with a possibility of being renewed for a further 15 years).

On top of this are federal “control orders”.

This is the kind of order imposed on David Hicks on his return from Guantanamo Bay, and on Joseph “Jihad Jack” Thomas after his acquittal for terrorism offences.

Control orders allow for an extremely wide range of restrictions and obligations to be imposed on a person if those conditions are “reasonably necessary, appropriate and adapted” to protecting the community from terrorism.

Control orders last for up to 12 months, but there are no limits on their renewal.

Under a supervision order or control order, Benbrika could be required to:

-

stay at a certain address

-

be subject to curfews (even amounting to home detention)

-

wear a tracking device

-

not use the internet, a phone or other devices

-

not contact certain people or go to certain places

-

undertake education, counselling or drug testing

-

or any number of other restrictions or obligations deemed necessary for community protection.

Breaching one of these orders is punishable by five years imprisonment.

But wouldn’t it be better to deport him?

There is a symbolic attraction to taking away the citizenship of someone who has acted in a way that shows no allegiance to – and even a violent disregard for – Australia and basic community values.

Indeed, the one judge who upheld the citizenship-stripping laws, Justice Simon Steward, did so on the basis that citizenship-stripping was not designed to punish.

Instead, he argued it was merely an acknowledgement that the person themselves had severed their ties to Australia.

A study looking at counterterrorism citizenship-stripping in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia found the laws were serving this symbolic role.

But symbolism is a thin shield for national security.

When it comes to actually protecting security, the evidence shows that citizenship-stripping comes up short.

People have been stripped of their citizenship and committed terrorist acts elsewhere. Khaled Sharrouf, Australia’s most notorious foreign fighter, is one such person.

In a globalised world, people stripped of citizenship can still serve a pivotal role in recruitment and radicalisation, especially on the internet.

Kept in Australia, as an Australian, the full weight of our vast security laws can be brought to bear on Benbrika.

Stripped of his citizenship, Benbrika would have been beyond the reach of those laws, and it would be naïve to think that simply making him not-Australian would negate the risks he may present.

Meta Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Approval of AI Chatbots Allowing Sexual Interactions With Minors

Meta Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Approval of AI Chatbots Allowing Sexual Interactions With Minors  U.S. Condemns South Africa’s Expulsion of Israeli Diplomat Amid Rising Diplomatic Tensions

U.S. Condemns South Africa’s Expulsion of Israeli Diplomat Amid Rising Diplomatic Tensions  US Judge Rejects $2.36B Penalty Bid Against Google in Privacy Data Case

US Judge Rejects $2.36B Penalty Bid Against Google in Privacy Data Case  CK Hutchison Unit Launches Arbitration Against Panama Over Port Concessions Ruling

CK Hutchison Unit Launches Arbitration Against Panama Over Port Concessions Ruling  Supreme Court Signals Skepticism Toward Hawaii Handgun Carry Law

Supreme Court Signals Skepticism Toward Hawaii Handgun Carry Law  Jerome Powell Attends Supreme Court Hearing on Trump Effort to Fire Fed Governor, Calling It Historic

Jerome Powell Attends Supreme Court Hearing on Trump Effort to Fire Fed Governor, Calling It Historic  Newly Released DOJ Epstein Files Expose High-Profile Connections Across Politics and Business

Newly Released DOJ Epstein Files Expose High-Profile Connections Across Politics and Business  Federal Judge Blocks Trump Administration Move to End TPS for Haitian Immigrants

Federal Judge Blocks Trump Administration Move to End TPS for Haitian Immigrants  CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences  Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit

Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit  Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links

Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links  Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies

Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies  Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding

Trump Administration Sued Over Suspension of Critical Hudson River Tunnel Funding  U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday  Federal Judge Restores Funding for Gateway Rail Tunnel Project

Federal Judge Restores Funding for Gateway Rail Tunnel Project  Google Halts UK YouTube TV Measurement Service After Legal Action

Google Halts UK YouTube TV Measurement Service After Legal Action  Supreme Court Tests Federal Reserve Independence Amid Trump’s Bid to Fire Lisa Cook

Supreme Court Tests Federal Reserve Independence Amid Trump’s Bid to Fire Lisa Cook