Since the 19th century May 1 has been International Worker’s Day, chosen by organised labour to celebrate the contribution of workers around the world. But it’s frequently forgotten that the day actually celebrates a particular achievement of the labour movement: being able to do less work. Not better paid or decent work, but shorter working hours.

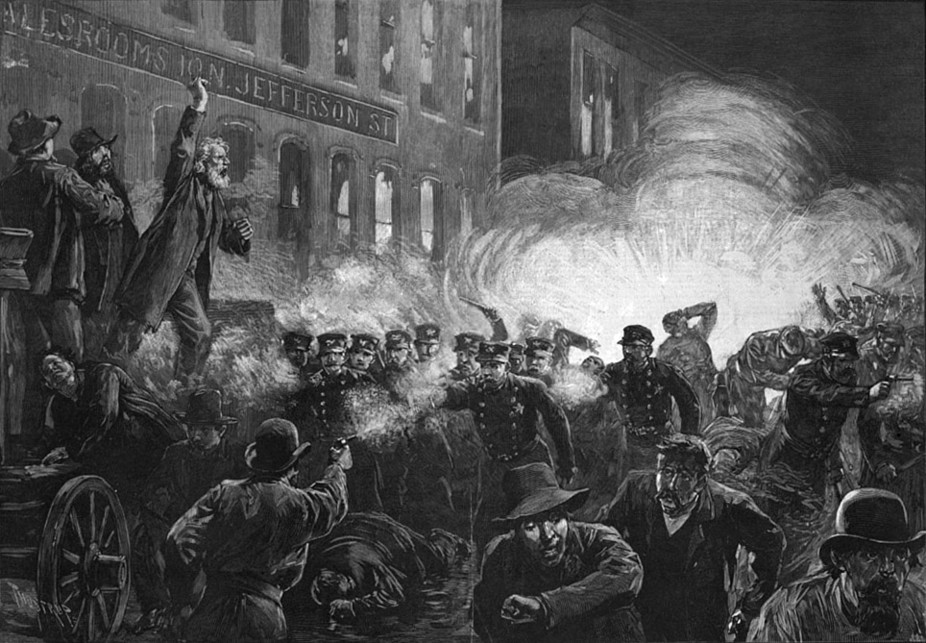

May 1 initially commemorated the 1886 Haymarket affair, where Chicago workers were striking for a radical and dangerous proposal: the eight-hour work day. This idea was so incendiary that the protests turned violent; both police and protesters died in the conflict.

Today more and more people around the world are facing precarity, casualisation, inequality and unemployment. It’s time to pursue a new agenda for a new global labour movement – or rather, to update the old agenda of the 19th century: less working time and more money for all, in the form of shorter work days and a universal basic income.

What happened to the struggle?

An eight-hour work day and weekends off were far from the norm for most full-time workers before the early 20th century. They usually worked 12 to 16 hours a day, six days a week. It took a protracted, often violent organised labour struggle in the face of strenuous opposition to change that.

Forty-hour work weeks were finally legislated around the world less than a century ago. This seemed like just the beginning. The economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1930 that thanks to technology, within a century we’d all stop worrying about subsistence. We’d work 15 hours a week, just enough to keep us from getting bored.

In some ways he was right. Technological advancement has exceeded his wildest dreams; productivity and output per worker has soared. But this has proven to be our problem rather than a source of liberation.

As productivity grew and each worker could produce ever more output, we consumed more and more stuff so that full time, 40-hour-a-week employment could stay stable. Now we’ve reached our limits, with climate change, pollution, deforestation and extinction spiralling out of control. We can’t afford to keep consuming ever more.

We’ve also moved into a different phase of automation, a “fourth industrial revolution” where artificial intelligence and machine learning can do the work of accountants, lawyers and other professionals.

The logical solution would be to enjoy such automation by working less (while the amount of stuff produced remains the same with machines’ help). Instead, those of us lucky enough to be formally employed still work nominally 40-hour weeks (in reality too often working far more) while ever more people can’t find any steady employment.

The fruits of soaring productivity growth and the wealth generated by automation are not being redistributed via rising salaries or shorter working hours. Instead they are captured by a tiny global elite. The richest 1% now has more wealth than the rest of the world put together. Yet there isn’t a mass organised struggle explicitly calling for a redistribution of wealth and work.

It’s time to revive a very old labour ideal. Industrial Workers of the World/www.iww.org

Instead, in places as varied as South Africa, the US and Europe increasingly frustrated, alienated populations faced with the rise of precarious work and wage stagnation point their finger at foreigners and immigrants. Their calls are not for redistribution, but for isolation and xenophobic exclusion.

South Africa is a prime example of this contradiction. It’s the most unequal major country in the world, with staggering wealth and unemployment rates. It has experienced years of deindustrialisation and jobless growth.

South Africa is experiencing the sorts of contradictions that follow in automation’s wake. Factory and even service jobs are being automated, and CEOs earn 541 times the average income. Meanwhile, people desperate for a wage resort to what anthropologist David Graeber terms “bullshit jobs” like pumping other people’s petrol or watching their parked cars.

South Africa’s inequality isn’t just a matter of income or wealth. It’s also a matter of working hours – some people have too many, some none at all.

From labour to leisure

An obvious solution would be to cut back on the standard work week so that demand for labour goes up.

Education institutions would have to scramble to fill some of the demand for skilled workers. But the pressure might be a good thing. It would push the school system to produce well-equipped graduates, and provide new solutions to problems such as the university fee crisis, spurring greater urgency for the state or private sector to underwrite higher education programmes.

This would also decrease inequality. The only way to keep wages the same while hiring more people is for wealth to get spread out: for the highest earners and others who capture the fruits of corporate profits (i.e., shareholders) to get less so workers get more.

Shortening working hours has also been linked with a host of other social goods like better health outcomes, less impact on the environment, higher gender equity, and increased happiness and productivity.

Labour must also be decommodified more broadly. Then even those unable to sell their labour in a rapidly automating world would reap some of automation’s fruits.

The simplest proposal to achieve this is the universal basic income guarantee: the idea that everyone gets enough cash every month to cover essential living costs, no matter what. It’s a redistributory measure. If you earn enough to not need it, you give it back to the communal pot when paying your taxes.

If that aspect is taken into account, the proposal is surprisingly affordable. It could also end poverty, stem inequality, enable work that isn’t valued by capitalist markets (such as care work or the arts), and empower workers to bargain for better conditions without the fear of starvation or homelessness.

What we need are shorter working hours and a universal basic income. In other words, a leisure movement – not a labour movement.

Radical, and attainable

Such a call is both radical and attainable. It’s attainable because it simply spreads out the gains from productivity growth. It’s radical because we live with the cultural ramifications of centuries of labour scarcity, when everyone had to work as much as possible to produce enough goods to go around. That’s not the case anymore, yet the old mentality remains: hard workers are morally superior, and laziness is unquestioningly a character flaw, a moral failing.

This is a default assumption not only among the middle and upper classes, but as my own and others’ recent research in South Africa and Namibia shows, among the unemployed poor as well.

This proposal is also radical because it challenges the unopposed accumulation of wealth amongst a small elite. It will certainly be opposed by the very wealthy. But then, so were calls for a 40-hour work week.

Elizaveta Fouksman has received funding from the Ford Foundation, the Rhodes Trust and the Oxford Department of International Development, and will shortly be funded by the Berggruen Institute. Liz is part of civil society advocacy committee in South Africa working on expanding social protection, together with representatives of several civil society organisations, among them the Black Sash and the Studies in Poverty and Inequality Institute.

Elizaveta Fouksman has received funding from the Ford Foundation, the Rhodes Trust and the Oxford Department of International Development, and will shortly be funded by the Berggruen Institute. Liz is part of civil society advocacy committee in South Africa working on expanding social protection, together with representatives of several civil society organisations, among them the Black Sash and the Studies in Poverty and Inequality Institute.

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate