For his forthcoming Budget on March 11, Chancellor Sajid Javid has promised to “unleash Britain’s potential – uniting our great country, opening a new chapter for our economy and ushering in a decade of renewal”. This was on the back of the Conservative Party’s 2019 election manifesto commitment “to use our post-Brexit freedoms to build prosperity and strengthen and level up every part of the country”.

Yet so far, the government of Boris Johnson has been noticeably vague as to precisely what is to be “levelled up” or over what time frame – beyond talking about more funding for schools, health, police and infrastructure in England. There are at least three very good reasons for being in no hurry to get into details.

1. The manifesto paradox

The Conservatives made manifesto commitments not to raise the rate of VAT, income tax or national insurance, and not to borrow to finance day-to-day current spending. Their plans to borrow to finance net public investment in infrastructure will not average more than 3% of GDP over the current parliament, and even those modest plans will be reassessed if debt interest reaches 6% of revenue.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, commitments already made on increased funding for the National Health Service (NHS) in England mean that, beyond the Department of Health and Social Care, total day-to-day spending on public services is “set to be 16% below 2010-11 levels (21% in per-person terms)”. So under current plans, austerity will continue for the majority of services in the majority of communities in England.

Yet having won its 80-seat majority on the back of punching significant holes in the Labour Party’s much vaunted “red wall” of constituencies across the midlands and north of England, the Johnson government will not be able to sate public expectations if its ambition is limited to a few high-profile infrastructure projects. The Johnson government therefore faces a strategic domestic political, ideological and policy dilemma of how to reconcile its fiscal conservatism with all the talk of uniting and levelling up.

2. The London dilemma

One possible solution would be for the government to redistribute resources away from the “southern powerhouse” of Greater London, the south east and east of England to stoke the “midlands engine” and that other powerhouse further north. Yet the government has just been warned against that course of action by both Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, and Paul Dreschler, the chair of business lobby group London First.

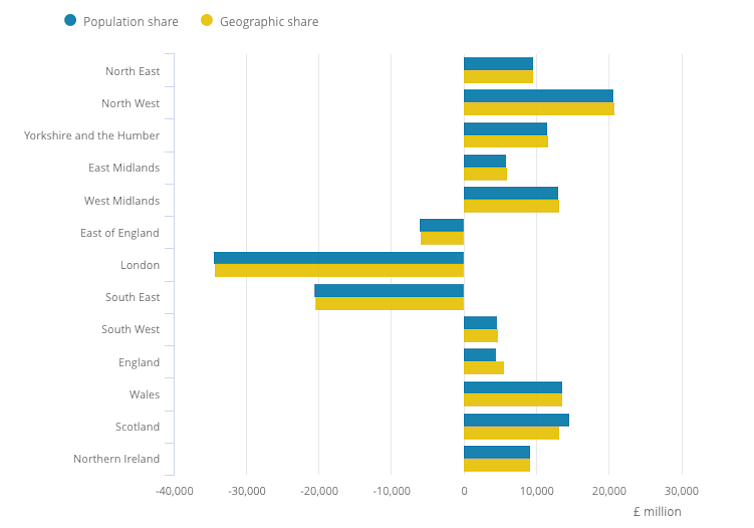

Lest the Treasury forget, on the tax revenue side of the national balance sheet, only London (£38.9 billion), the south east (£21.9 billion) and the east of England (£4.2 billion) actually produced net fiscal surpluses in the financial year ended March 31 2019. Everywhere else was in deficit, including the north west (£20.1 billion), the north east (£10.7 billion) and Yorkshire and the Humber (£11.3 billion), Scotland (£14.8 billion) and Wales (£13.4 billion). It won’t be easy to reduce inequality without killing the golden goose – or at least giving it a few bruises.

3. The bad lieutenants

There is no shortage of blueprints on what might be done. Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson’s chief special adviser, has identified A Resurgence of the Regions, a paper by Richard Jones, a professor in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Sheffield, as an agenda “about how the new government could really change our economy for the better, making it more productive and fairer”.

Jones’ 2019 paper outlined a classic technocratic blueprint for more direct strategic intervention “to build up the innovation capacity of those regions of the UK which currently are economically lagging”. He advocates rebuilding innovation outside the south east by establishing institutes that would translate research into actual commercial products and services, and foster similar ecosystems for innovation to those in London and Cambridge – while allowing different regions to pursue deviations that suited their strengths.

Hitherto, the principal proponent of such thinking within the Conservative Party was the arch-Remainer Michael Heseltine. He urged the Cameron government to “leave no stone unturned” in pursuing growth in the English regions, and advised the May and Johnson governments to create a new dedicated department.

This would mean a return to the politics of the government of Edward Heath, who, like Heseltine, envisaged large-scale Whitehall intervention via a national industrial strategy. Rejecting such dirigisme, Margaret Thatcher was more open to ideas about moving towards a German social market economy focused on individual entrepreneurship, risk-taking and market competition.

Johnson is reported to have told his cabinet colleagues that he was “basically a Brexity Hezza”. But to even contemplate a return to such interventionism would be to court open ministerial revolt from a government containing all five authors of the quintessential Thatcherite work from 2012, Britannia Unchained – including Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, Home Secretary Priti Patel and International Trade Secretary Liz Truss.

Britannia Unchained advocated unleashing Britain’s potential by dismantling the chains of public subsidy, taxes, welfare dependency and stifling regulation. The aim was to raise prosperity by encouraging a buccaneering entrepreneurial spirit, shaped by “graft, risk and effort in pursuit of long-term rewards”. Technocratic intervention was definitely not the order of the day.

In shaping the political priorities of the March budget, Johnson therefore has another very difficult mission on his hands. How to reconcile the conflicting constituencies of the north and south, of fiscal conservatism and levelling up; and how to pull it all off without poisoning relations with his key lieutenants. In short, “getting Brexit done” could be the least of his worries.

Ecuador Raises Tariffs on Colombian Imports to 50% Amid Border Security Dispute

Ecuador Raises Tariffs on Colombian Imports to 50% Amid Border Security Dispute  Rubio Urges Caribbean Cooperation on Crime as U.S. Tightens Cuba Policy

Rubio Urges Caribbean Cooperation on Crime as U.S. Tightens Cuba Policy  Keir Starmer Faces Crucial By-Election Test in Manchester Amid Tight Three-Way Race

Keir Starmer Faces Crucial By-Election Test in Manchester Amid Tight Three-Way Race  Venezuela Oil Exports to Reach $2 Billion Under U.S.-Led Supply Agreement

Venezuela Oil Exports to Reach $2 Billion Under U.S.-Led Supply Agreement  Philippines, U.S., and Japan Conduct Joint Naval Drills in South China Sea to Boost Maritime Security

Philippines, U.S., and Japan Conduct Joint Naval Drills in South China Sea to Boost Maritime Security  U.S.-Canada Trade Talks Resume as Trump Administration Reviews USMCA

U.S.-Canada Trade Talks Resume as Trump Administration Reviews USMCA  UBS Boosts Chinese Tech and AI Stocks for 2026 as Sector Eyes Strong Growth

UBS Boosts Chinese Tech and AI Stocks for 2026 as Sector Eyes Strong Growth  Claudia Sheinbaum Confirms Call With Trump After El Mencho Killed in Major Mexico Cartel Raid

Claudia Sheinbaum Confirms Call With Trump After El Mencho Killed in Major Mexico Cartel Raid