There was some worrying news for Volodymyr Zelensky this week when the US House of Representatives finally elected a new speaker. Mike Johnson, a Republican congressman from Louisiana, has consistently opposed US funding for the Ukrainian war effort. Now he’s the second most powerful man in US politics behind the president, Joe Biden.

As Thomas Gift, the director of the Centre on US Politics at UCL spells out, Johnson’s cooperation will be vital if Biden is to get his latest US$105 billion (£86.5 billion) national security aid package through Congress. More than$60 billion of that is earmarked for Ukraine and if it doesn’t come through, Kyiv will struggle.

Of course, Washington has other fish to fry. Whether you can call the Israel-Hamas war a “bigger fish” remains unclear. Only $14 billion has been earmarked to go to Israel so far. But for most people in the US events in Israel and Gaza are seen as being of the highest importance. Israel has replaced Ukraine as the lead story on most news channels and knocked the European war off the front pages. With Donald Trump relentlessly demanding a moratorium on aid to Ukraine, Kyiv has clear grounds for concern as its counteroffensive grinds on in the south with still no end to the killing in sight.

Russia meanwhile is struggling with its own offensive in the east. According to a recent report published by the UK’s Ministry of Defence, the Russian push around the town of Avdiivka in the Donetsk Oblast has run into heavily fortified Ukrainian defensive positions (similar to what Ukrainian forces in the south are experiencing with entrenched Russian troops).

The MoD update, dated October 17, says that heavy casualties have forced Russia from the offensive into what it calls “active-defence”. Death tolls vary widely and should be taken with a grain of salt, but Newsweek claimed in a report on October 20 that Russia’s death toll was approaching 300,000 men, including 1,300 killed in a single day.

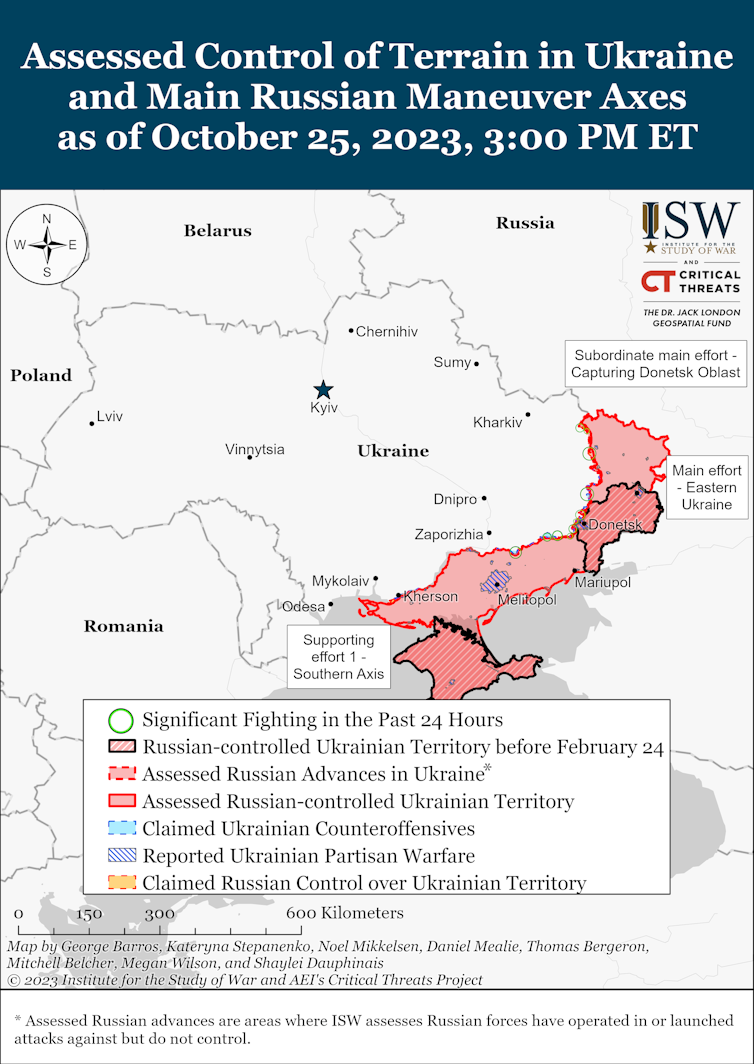

The state of the war in Ukraine as at October 25 according to the Institute for the Study of War. Institute for the Study of War

But plenty of men still appear to be joining up – at least, according to Dmitry Medvedev, former Russian president, deputy national security minister and outspoken Putin mouthpiece, who said 385,000 men had enlisted so far this year. So the burning question is whether and when the Russian public will get tired of the bodybags and the news from friends or relatives that a loved one has been killed or maimed at the front.

Ben Soodavar, of the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, believes that military loss is deeply embedded in the Russian psyche. Most Russians are brought up with tales of self-sacrifice in the second world war – the heroes of the Red Army who made the world safe from fascism. “For Russia, every dead soldier in Ukraine constitutes a step towards victory and reclaiming the great power image of the country’s Soviet past,” he writes.

It helps, of course, that the head of the Russian Orthodox church is as good as promising soldiers the keys to the kingdom of heaven if they are killed in the line of duty.

War at sea…

If the war on land continues to grind on, with every metre of land bitterly contested, the sea war took an interesting turn recently when it was revealed that Russia has relocated many of the vessels in its Black Sea fleet from its base in Sevastopol in Crimea to safer bases in Novorossiysk and Feodosia, on either sides of the Kerch strait connecting eastern Crimea with the Russian mainland. There are even reports of plans to build naval facilities in the breakaway Georgian region of Abkhazia.

Zelensky claimed on October 24 that: “The Russian fleet is no longer able to operate in the western part of the Black Sea and is gradually fleeing from Crimea. And this is a historic achievement.”

Strategic hotspot: Ukraine is claiming that Russia has lost control of the northwestern Black Sea. Peter Hermes Furian/Shutterstock

Basil Germond, a researcher in maritime strategy at the University of Portsmouth, believes this is a significant moment, marking Russia’s inability to properly enforce any blockade of Ukraine’s grain shipments. It also makes Russia look weak in Crimea itself, which, as Germond points out, “is a big problem, given the central role that Crimea plays in Putin’s imperialist narrative”.

… and in cyberspace

Another theatre of war not much discussed thus far is cyberspace. Russia has long been thought of as a master of cyberwarfare, spreading disinformation, launching attacks against western systems and disrupting communications. But now Kyiv has formed its own “IT army”, launching disruptive cyber-attacks and data thefts against the Russian government and other high-profile targets such as energy giant Gazprom.

Launched in February by the deputy prime minister, Mykhailo Fedorov, it is thought to be the first time that a state official has openly called on hackers from around the globe to join a nation’s military defensive efforts against an invading force. Vasileios Karagiannopoulos, who researches cybercrime and security at the University of Portsmouth, says the army has pulled off a number of coups, including hacking into Russian state TV channels to broadcast a message that: “the hour of reckoning has come.”

Karagiannopoulos believes this is the tip of the cyberwar iceberg and that a great deal of work is needed to incorporate activities in cyberspace into the rules of war.

Putin and Xi, a new world order?

Putin may not have been able to travel to South Africa for the Brics summit earlier this year for fear he might be and face war crimes charges at the International Criminal Court. But when China celebrated the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Beijing last week, Putin was there, front and centre, taking every opportunity to bask in the reflected glory of his apparently “no-limits friendship” with Chinese president Xi Jinping.

Stefan Wolff, an international relations expert at the University of Birmingham, noted the asymmetry of this friendship. While Xi travelled to Moscow in March for a one-on-one with the Russian leader, Putin had to content himself with being one of many leaders in Beijing, and while he made the most of it for the Russian press, the occasion was all about Xi and his Belt and Road project.

Writing after the summit, Natasha Kuhrt, a senior lecturer in international peace & security at King’s College London and Marcin Kaczmarski, who lectures in security studies at the University of Glasgow, observed what they described as “Putin’s explicit acknowledgement of the different roles played by Moscow and Beijing in international politics”.

They note that despite the presence of a number of high level representatives of Russian business, no contracts of note were announced, perhaps a sign of China’s wariness of openly deriding the west’s sanctions regime. And, for all Putin’s boasts of the volume of trade between the two countries, the bulk of this trade consists of export of Russian hydrocarbons and other raw materials to China. In the 1990s, Russia feared becoming a “raw materials appendage” to China. As Kuhrt and Kaczmarski note, this appears to be becoming a reality.

Trapped doing business in Russia

Meanwhile, more than 600 days since Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine and Russia was hit by increasingly stringent western sanctions, more than 1,400 international companies are still operating in Russia, many of them unwillingly.

Simon Evenett, a professor of international trade and economic development at the University of St Gallen, and Niccolò Pisani, a professor of strategy and international business at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), have explored why some multinationals have been trapped in Russia, finding it very difficult, if not impossible, to exit the country. They explore four push and pull factors that have help explain why this is.

Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality

Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality  India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out

India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out  Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges

Ohio Man Indicted for Alleged Threat Against Vice President JD Vance, Faces Additional Federal Charges  Sydney Braces for Pro-Palestine Protests During Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s Visit

Sydney Braces for Pro-Palestine Protests During Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s Visit  Trump Signs “America First Arms Transfer Strategy” to Prioritize U.S. Weapons Sales

Trump Signs “America First Arms Transfer Strategy” to Prioritize U.S. Weapons Sales  Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall

Japan Election 2026: Sanae Takaichi Poised for Landslide Win Despite Record Snowfall  Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy

Jack Lang Resigns as Head of Arab World Institute Amid Epstein Controversy  Nicaragua Ends Visa-Free Entry for Cubans, Disrupting Key Migration Route to the U.S.

Nicaragua Ends Visa-Free Entry for Cubans, Disrupting Key Migration Route to the U.S.  Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  Trump Congratulates Japan’s First Female Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi After Historic Election Victory

Trump Congratulates Japan’s First Female Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi After Historic Election Victory  Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify

Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify  Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics

Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi Secures Historic Election Win, Shaking Markets and Regional Politics  Anutin’s Bhumjaithai Party Wins Thai Election, Signals Shift Toward Political Stability

Anutin’s Bhumjaithai Party Wins Thai Election, Signals Shift Toward Political Stability  Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters

Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters  Pentagon Ends Military Education Programs With Harvard University

Pentagon Ends Military Education Programs With Harvard University  US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks

US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks  Bosnian Serb Presidential Rerun Confirms Victory for Dodik Ally Amid Allegations of Irregularities

Bosnian Serb Presidential Rerun Confirms Victory for Dodik Ally Amid Allegations of Irregularities