Almost one in five Australians think introduced horses and foxes are native to Australia, and others don’t want “cute” or “charismatic” animals culled, even when they damage the environment. So what are the implications of these attitudes as we help nature recover from bushfires?

Public opposition to culling programs is often at odds with scientists and conservationists.

These tensions came to the fore last month when scientists renewed calls for a horse-culling program to protect native species in Kosciusko National Park – a move strongly opposed by some members of the public.

To manage the environment effectively, including after bushfires, we need to understand the diversity of opinion on what constitutes a native animal, and recognise how these attitudes can change.

Governments are responding

In Australia, native species are usually defined as those present before European settlement in 1788. Lethal pest control usually targets species introduced after this time, such as horses, foxes, deer, rabbits, pigs, and cats.

But fire makes native fauna more vulnerable to introduced predators. Fire removes ground layer vegetation that small wildlife would use as protective cover. When this cover is gone, these animals are easier targets for predators like cats and foxes.

State governments have started to respond to this impending crisis. In January, the New South Wales government announced its largest ever program to control feral predators, in an effort to protect native fauna after the fires.

The plan includes 1500-2000 hours of aerial and ground shooting of deer, pigs, and goats and distributing up to a million poison baits targeting foxes, cats, and dingoes over 12 months.

Similarly, the Victorian government announced a A$17.5 million program to protect biodiversity the fires affected, including A$7 million for intensified management of threats like introduced animals.

But will the public be on board? Widespread media coverage of the recent fires and their impacts on wildlife, including the loss of more than a billion animals, might garner support for protecting native wildlife from pests.

On the other hand, efforts to manage animals such as cats and horses might be hampered by a lack of public support for culling charismatic animals that many people value or view as belonging in Australia now.

Different folks, different strokes

The distinctions many Australians draw – native animals are “good” and introduced species are “bad” – shape how people view conservation efforts. A survey we conducted in 2017 found people more likely to disapprove of lethal methods for managing species they perceived to be native.

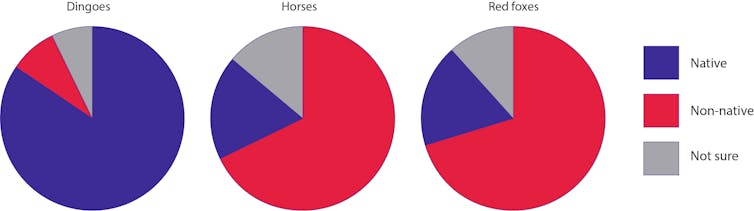

In the same survey, we found nearly one in five Australians considered horses and foxes to be native to Australia.

This suggests either that a) people lack knowledge of Australia’s natural history or b) people disagree with conservationists’ definition of animal “nativeness”.

Many introduced species, such as horses and foxes, have existed in Australia for more than a century and have established populations across much of the country. It’s unlikely they’ll ever be eradicated.

Some people, including scientists, say we should just accept introduced species as part of Australia’s fauna. They argue current management justifies killing based on moral, not scientific judgements and introduced animals may increase biodiversity.

But the issue remains extremely divisive. A central tenet of traditional conservation is that humans have a duty to protect native species and ecosystems from the threat introduced species pose. It’s difficult to do this without culling introduced animals.

Animal welfare concerns may also drive opposition to culling, taking the view that all animals, even non-natives, have intrinsic value and the right to live.

What’s more, non-native culling programs can be controversial when the animal is considered “cute” or “charismatic”, or of cultural value. For example, a plan to cull feral horses in the Kosciusko National Park in 2018 was met with public outrage, prompting the NSW government to overturn the decision.

Yet protecting introduced species in national parks goes against the very reason they were created – to conserve native ecosystems and species.

Some animals are more equal than others

When analysing public attitudes towards various species, we must also consider how attitudes shift over time.

In Australia, non-native animals such as domestic camels and donkeys were considered useful for transport and highly valued. But we ultimately turned them loose and relabelled them as pests when we started using cars.

We asked the Australian public whether they viewed dingoes, horses, and foxes as native or non-native in Australia. van Eeden et al. (2020)

Interestingly, we’ve already accepted some introduced species as native. Humans brought dingoes to Australia at least 3,500 years ago. They’re described as native under Australian biodiversity legislation, and 85% of our 2017 survey participants considered dingoes to be native.

Perhaps its only a matter of time until more recently arrived species like horses and foxes are counted as native. Some scientists argue this shift should be based on how ecosystems and species adapt to these new arrivals. For example, some small Australian mammals show fear of dingoes or dogs, but they haven’t yet learnt to fear cats.

Native species can be pests too

Native species, such as kangaroos and possums, may also be culled if they’re perceived to be overabundant or damaging economic interests like agriculture.

While the plight of bushfire-affected koalas on Kangaroo Island attracted considerable media interest, and the immediate welfare of any animal affected by fires is always a concern, koalas were actually introduced there.

They’ve been managed as a pest on Kangaroo Island for more than 20 years, and it’s unlikely the rescued koalas will be returned to the island. In this case, public concern transcends the distinction between native and introduced.

Public perception is important

We might never all agree on how best to manage native and non-native species. But effective environmental management, including after bushfires, requires understanding the diversity of opinion.

Doing so can help to develop management plans the public supports and allow effective communication about management that is controversial.

In fact, the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage did undertake an extensive public consultation process in developing their horse management plan for Kosciuszko National Park, but it wasn’t used after the “brumby bill” gave horses protection in 2018.

With human lives and many animal lives lost, response to the bushfires is already highly emotive. Failure to consider public attitudes towards managing animals will lead to backlash, wasted money and time, and continuing decline of the native species whose conservation is the goal of these actions.

We combed through old botanical surveys to track how plants on Australia’s islands are changing

We combed through old botanical surveys to track how plants on Australia’s islands are changing  Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research

Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research  As the Black Summer megafires neared, people rallied to save wildlife and domestic animals. But it came at a real cost

As the Black Summer megafires neared, people rallied to save wildlife and domestic animals. But it came at a real cost  Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history

Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history  LA fires: Fast wildfires are more destructive and harder to contain

LA fires: Fast wildfires are more destructive and harder to contain  GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’

GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’  How to create a thriving forest, not box-checking ‘tree cover’

How to create a thriving forest, not box-checking ‘tree cover’  Parasites are ecological dark matter – and they need protecting

Parasites are ecological dark matter – and they need protecting  Ukraine minerals deal: the idea that natural resource extraction can build peace has been around for decades

Ukraine minerals deal: the idea that natural resource extraction can build peace has been around for decades  Fertile land for growing vegetables is at risk — but a scientific discovery could turn the tide

Fertile land for growing vegetables is at risk — but a scientific discovery could turn the tide  Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys

Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys  How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus

How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus