It’s taken for granted in many if not most school environments today that digital technology should be integrated throughout the curriculum to enhance not only communication and creativity but also equal access to resources and opportunities.

Digital skills are considered critical for youth navigating the world — and for gaining mobility. Mobility is understood to mean both the nimbleness to communicate and enter into cross-cultural forums or dialogues (into new kinds of cultural “spaces” through internet platforms or digital technologies) and the capacity to move across socio-economical and cultural groups in everyday life.

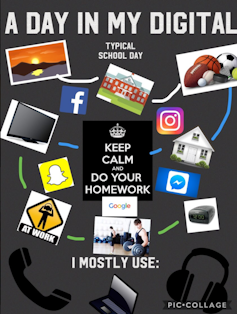

A young person’s representation of their digital day.

While it’s critical for literacy educators to support student inquiry through digital media, is it the case that because young generations grew up as “digital natives” the tools of technology are inherently preferable today for fostering creativity? And when digital technologies foster mobility into new spaces, how do youth experience this?

As researchers who study what it means to be creative and literate today, we wanted to explore these questions and to gain insight into how young people think about digital media and their young digital lives.

Scotland, Canada youth

Diane was researching in Hamilton, west of Toronto, near the U.S. border. Hamilton has a population of more than 500,000 and has a long history with the steel industry. Mia was researching in Glasgow, Scotland, which has a similar-sized population and has an even longer history of industry in shipbuilding.

Both cities have seen dramatic shifts in their labour markets and economies due to the demise of their historic industries.

Youth Mobilities in Public and Digital Spaces group, Glasgow, Scotland. (Mia Perry), Author provided

Through our collaborative project, Youth Mobilities in Public and Digital Spaces (YOMO), we brought together artists, youth, research assistants and community partners in the two different cities to form comparative research cohorts.

We concluded that when young people opt for screens in the home, on the bus or secretly under the desk at school, it’s almost entirely due to the options of engagement at their disposal. And we found that digital platforms don’t in themselves itself bridge geographical, socio-economic or cultural differences. The way people navigate digital spaces — their experience of being online doing something — depends on their experiences, their geographical locations or contexts and their preferred ways of expressing themselves.

Young digital lives

Through collaboration with artists and young people, we hoped to develop a research approach that was less predictable but participatory, and would allow us to gain new insights into young people’s digital lives.

Diane consulted with the public library of Hamilton, the Social Planning Research Council, local school boards, neighbourhood councils and a few guidance counsellors to recruit youth. The group met in the Red Hill library in the city’s east end.

Youth Mobilities in Public and Digital Spaces group, Hamilton, Canada. (Diane Collier), Author provided

In Glasgow, Mia worked with a neighbourhood board and the Centre for Contemporary Arts and established a group that met in the Garnethill neighbourhood. The groups, which met once a week for two to three months, were socio-economically diverse and a portion of the young people were planning for university.

Artists designed sessions

We talked to the artists about concepts that we thought were important to digital lives (such as space, social media, preferred modes and tools and feelings of ownership) but we also gave the artists the freedom to get to know the young people and to design their own sessions. Rather than focus on research questions, as we were, the artists honed in on artistic production.

A youth moulds clay icons. (Mia Perry), Author provided

We explored with young people their digital lives, the phones and laptops they used to communicate and the kinds of activities they engaged in. We asked the young people to interview friends about their digital lives — for example, what digital spaces felt familiar and comfortable — and to rate their online use from high to low. Leaders showed youth how to collect research data such as through collecting artefacts or doing interviews and youth had time and space to analyze data.

The visual artist in Hamilton led the youth to experiment with digital tools like green screens and 3D printers, and to create personal and group collages with arts materials and with digital tools. The sculptor in Glasgow encouraged three-dimensional representation. The young people in both sites made things like plasticine worlds and plaster hands, cut-out collages and maps, and used digital tools to develop these creations further.

Youth spaces

We learned that this kind of work is difficult. We learned that some of our pre-formed questions were ill conceived, such as: What kind of digital space do you think is yours?

Youth didn’t think of spaces (or apps or tools) as digital or otherwise. Many did not separate online and offline space.

Hamilton youth with the YOMO project in a video lab. (Diane Collier), Author provided

For example, when youth talked about spaces they felt were theirs, one person did say his phone — the only place he could be alone. But youth also talked about watching YouTube in their room, on their bed or with a friend. In other words, they conceived of the activities of being somewhere in a particular place with digital media as related or entwined.

Young people were not discriminatory against non-digital stuff. And the young people showed us this regardless of where they were, their ages or their backgrounds. The screens were often left untouched, and youth chose art materials.

Creating options

We need to spend as much time considering the options and choices for engagement, learning, making, interacting and playing, as we do considering what can be done with digital space for learning.

Youth experimented with paints, pasticene, sculpting and a wide variety of digital media. (Diane Collier), Author provided

Digital education is not a tool for the better delivery of pre-existing knowledge, skills or ways of reading and interacting with the world.

Even in our local groups, communication was challenging. Everyone had a specific and narrow preference for the platforms they used to communicate, text or talk. Each person had a set range of digital spaces where they explored and (sometimes) were expert. Just reminding the group about meetings required a collage of tailored approaches.

Engaging with digital tools and spaces doesn’t in and of itself bridge cultures and geographies. Such engagement serves as a new type of playground where young learn how to interact for particular and diverse objectives.

SpaceX Seeks FCC Approval for Massive Solar-Powered Satellite Network to Support AI Data Centers

SpaceX Seeks FCC Approval for Massive Solar-Powered Satellite Network to Support AI Data Centers  Google Cloud and Liberty Global Forge Strategic AI Partnership to Transform European Telecom Services

Google Cloud and Liberty Global Forge Strategic AI Partnership to Transform European Telecom Services  AMD Shares Slide Despite Earnings Beat as Cautious Revenue Outlook Weighs on Stock

AMD Shares Slide Despite Earnings Beat as Cautious Revenue Outlook Weighs on Stock  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race

Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race  TSMC Eyes 3nm Chip Production in Japan with $17 Billion Kumamoto Investment

TSMC Eyes 3nm Chip Production in Japan with $17 Billion Kumamoto Investment  Elon Musk’s SpaceX Acquires xAI in Historic Deal Uniting Space and Artificial Intelligence

Elon Musk’s SpaceX Acquires xAI in Historic Deal Uniting Space and Artificial Intelligence  SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers

SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  Sam Altman Reaffirms OpenAI’s Long-Term Commitment to NVIDIA Amid Chip Report

Sam Altman Reaffirms OpenAI’s Long-Term Commitment to NVIDIA Amid Chip Report