For nearly two centuries, rock-climbing and photography have been tightly intertwined, spectacularly roped together on knife-edge arêtes, vertiginous overhangs and seemingly sheer cliff faces.

Simon Carter’s stunning forthcoming collection of photographs, The Art of Climbing (2024), illustrates the heights reached by this mutually supportive partnership. They beautifully capture breathtaking feats of strength and agility made possible by some of the world’s most extraordinary geological formations.

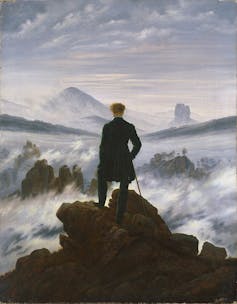

As a recognisable leisure pursuit, recreational rock-climbing began in the late 18th century as part of the wider development of mountaineering. The sport’s strong visual appeal was always apparent, captured most famously in Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

The piece anticipates many of Carter’s photographs with its placement of the human figure in a precipitous location against a sublime background of peaks, pinnacles and swirling mist. In particular, the image of Leo Holding at full stretch on Mount Huashan, China, which is used as the first double-page spread in Carter’s volume.

Even before mountaineering entered its so-called Golden Age in 1854, when Alfred Wills made an ascent of the Alpine peak The Wetterhorn, developments in early photography were making it possible to capture mountain images. In 1849, the art critic and philosopher of mountain scenery John Ruskin made what he claimed to be the “first sun portrait of the Matterhorn”, using the photographic process invented by Louis Daguerre.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich (1817). Hamburger Kunsthalle

Another pioneer of this early form of photography, Joseph Tairraz, captured some of the earliest images of ascents of Mont Blanc in the 1880s. He founded a four-generation dynasty of photographic climbers based in Chamonix, France, at the mountain’s base.

This family’s work illustrates the extraordinary development of climbing photography across the ages. From George Tairraz Snr’s images of gentleman in top hats and crinoline-skirted women exploring the Mer de Glace in 1910, to the younger George’s famous shot of the great French climber Gaston Rébuffat standing atop the needle-like L’aiguile du Roc (The Needle of the Roc).

This dizzying shot takes Friedrich’s Wanderer to new peaks of daring. And it anticipates the opening section of Carter’s book, Formations, which focuses on climbs of the extraordinary 65m-high dolerite column, the Totem Pole, on Tasmania’s east coast.

Both Tairraz’s and Carter’s work achieve a powerful synergy of the climber and the landscape, revealing a striking harmony of human and natural forms at the very limits of both.

Global climbing photography

In the second half of the 19th century, photographs became more important for climbing.

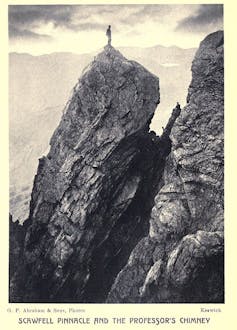

Rock climbing in the Lake District, captured by the Abrahams. University of California Libraries

They gradually replaced engravings, woodcuts and lithographs as the major visual form for presenting information about mountains, recording climbing achievements and capturing the dramas and disasters that happened in high places.

The Alpine Journal, the publication of the world’s first climbing club founded in 1857, reproduced its first mountaineering photograph in 1865. Later the same decade, they published guidance for aspiring climbing photographers in the article Notes on Photography in the High Alps.

The climbers, authors and photographers George and Ashley Abraham were particularly important in the development of the kind of sports-climbing photography featured in Carter’s new book.

The brothers’ photographs, taken between the 1890s and 1920s, were captured with a tripod-mounted wooden box camera. They featured pioneering climbs undertaken by moustachioed figures in flat caps, tweeds and nailed boots, protected only by a rope tied around their waist.

Like Carter’s volume, these images capture the physicality and grit required to complete demanding routes. Carter even offers an amusing visual echo of one famous Abraham brothers’ photograph of the “barn door traverse, Wasdale Head” – a spiderman-like climb of a stone building – in a shot of himself traversing the walls of a suburban shopping centre in Canberra, Australia.

Vittorio Sella’s photograph of Siniolchu in the Himalayas, taken from the Zemu Glacier in 1899. Wiki Commons

The careers of two of the most highly regarded mountaineering photographers of this period reveal how climbing was becoming increasingly global, moving beyond “the playground of Europe” (the mountaineer Leslie Stephen’s term for the Alps).

William Frederick Donkin (1845-1888), who has been described as “the greatest Alpine photographer of his day”, made his reputation in the Alps before dying in Caucasus in 1888. These environments were also subjects for Vittoria Sella (1859-1943).

Sella, a distinguished climber who made several notable first winter accents, accompanied his fellow Italian, Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, to the Karakoram and western Himalaya in 1909. During their trip he produced some of the finest photographs of climbing in the world’s highest mountains.

Extreme climbing, extreme photography

It is indicative of the close relation between photography and climbing, even in the most extreme locations, that one of the great mountaineering mysteries is the question of what happened to George Mallory’s and Andrew Irvine’s camera on their fatal attempt on Mount Everest in 1824.

Should the camera ever be recovered, its century-old images would offer possible confirmation of whether the two British mountaineers were the first to reach the world’s highest summit.

One hundred years later, our fascination with human endeavour in spectacular and inspiring landscapes continues. The Art of Climbing fully justifies the implicit claim of its title, revealing that photography has not only offered a spectacular record of achievement on rock but, as a form, has reached the elevated heights of art.

JD Vance to Lead U.S. Presidential Delegation at Milano Cortina Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony

JD Vance to Lead U.S. Presidential Delegation at Milano Cortina Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony  From Messi to Mika Häkkinen: how top athletes can slow down time

From Messi to Mika Häkkinen: how top athletes can slow down time  ‘The geezer game’ – a nearly 50-year-old pickup basketball game – reveals its secrets to longevity

‘The geezer game’ – a nearly 50-year-old pickup basketball game – reveals its secrets to longevity  Why Manchester City offered Erling Haaland the longest contract in Premier League history

Why Manchester City offered Erling Haaland the longest contract in Premier League history  Australia’s major sports codes are considered not-for-profits – is it time for them to pay up?

Australia’s major sports codes are considered not-for-profits – is it time for them to pay up?  Trump Set to Announce Washington D.C. as Host of 2027 NFL Draft

Trump Set to Announce Washington D.C. as Host of 2027 NFL Draft  Trump Urges Hall of Fame Induction for Roger Clemens Amid Renewed Debate

Trump Urges Hall of Fame Induction for Roger Clemens Amid Renewed Debate  Why the Australian Open’s online tennis coverage looks like a Wii sports game

Why the Australian Open’s online tennis coverage looks like a Wii sports game  NBA Returns to China with Alibaba Partnership and Historic Macau Games

NBA Returns to China with Alibaba Partnership and Historic Macau Games  Native American Groups Slam Trump’s Call to Restore Redskins Name

Native American Groups Slam Trump’s Call to Restore Redskins Name  LA28 Confirms Olympic Athletes Exempt from Trump’s Travel Ban

LA28 Confirms Olympic Athletes Exempt from Trump’s Travel Ban  What makes a good football coach? The reality behind the myths

What makes a good football coach? The reality behind the myths  Trump Plans UFC Event at White House for America’s 250th Anniversary

Trump Plans UFC Event at White House for America’s 250th Anniversary  How did sport become so popular? The ancient history of a modern obsession

How did sport become so popular? The ancient history of a modern obsession  Champions League final 2025: a battle for glory against a backdrop of money and fashion

Champions League final 2025: a battle for glory against a backdrop of money and fashion  Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push

Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push