To the relief of many in the BBC, the proposals in the government’s White Paper appear relatively modest compared to what many expected. If voices on the right had their way, the government would have scrapped the licence fee and effectively ended the BBC’s special status as a public broadcasting service with state funding. Instead it might have ended up as a subscription-based competitor to Netflix.

From the left, too, the BBC has been under attack – this time for its perceived establishment prejudice against the Labour leadership under Jeremy Corbyn and against the Yes side in the Scottish independence referendum. Yet the BBC remains stubbornly popular with the public – just like the UK’s other great national public institution, the NHS. That may well have protected it from the direst predictions about the White Paper. It certainly cannot be taken for granted in future, however.

The BBC has always defended its cherished “independence” and looks uneasy about the new proposal for almost 50% of its board to be appointed by the government. A response is that at least the government has some kind of democratic mandate. One remarkable truth about the corporation is that the British public is rarely considered in the debate. Never mind that it pays for the BBC to be its servant.

Whose Auntie?

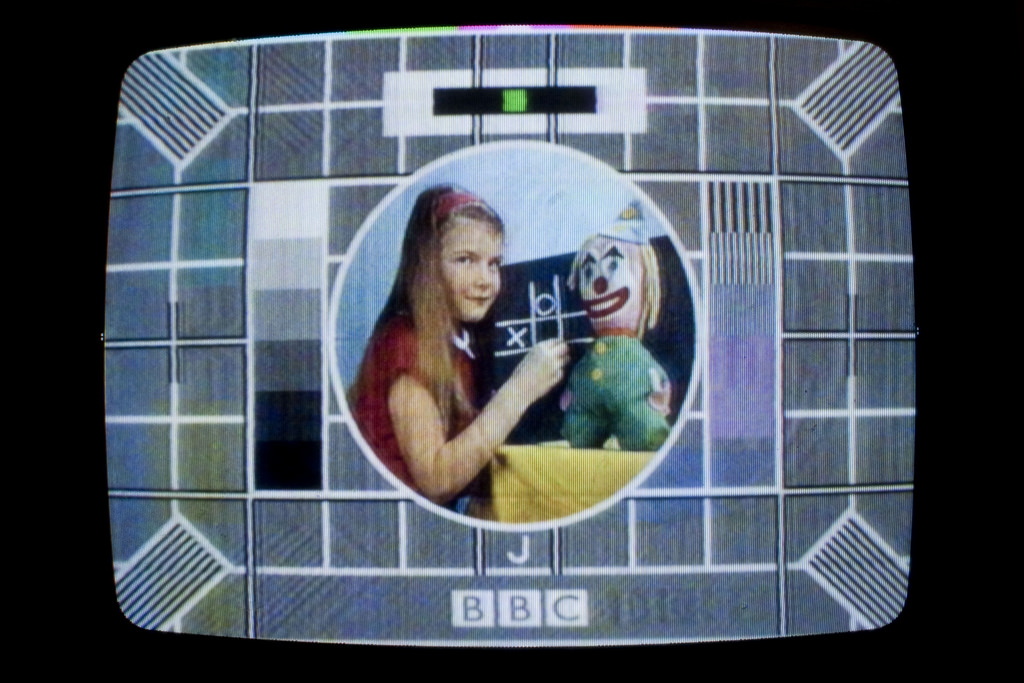

Because the BBC was constituted at arm’s length from government, it has always enjoyed a certain autonomy. But this also made it a creature of the “great and the good”, personified by its founder Lord Reith and his paternalist values. It betrayed a lack of trust in “the masses” by the social elites that ran the British Empire.

The BBC nonetheless developed an independent public-service ethos in the more tightly regulated national-media era of the 1950s and 1960s. This is arguably the root of its enduring popularity, and lives on through the likes of Radio 3, Radio 4 and the Asian Network. Yet imposing all this without consulting the public always smacks of metropolitian elitism.

The BBC’s public service is also a long way from what it was. Since at least the days of John Birt’s very market-oriented director generalship in the 1990s, the corporation has been regularly accused of losing this ethos. In the scramble for mass-market ratings in the fragmented TV world of the 21st century, it produces much less critical and innovative programming than it used to. It is hard to compare today’s fare with the heyday of Play For Today and prime-time slots for landmark documentaries and fearless current affairs coverage.

Complaints about the BBC apeing its competitors and invading the natural space of the private sector are another long-running theme. There has been much talk about removing prime-time giants like Strictly Come Dancing, and most recently the BBC has announced it will take down most recipes from its website to placate its critics.

So will the public continue to stay onside to protect all this? The lack of trust in the public that was built into the BBC’s foundations is now being reciprocated by a growing public hostility to the political and media classes on the back of television fakery, Leveson, Iraq, the financial crisis, Jimmy Savile and all the rest. The cultural gap between the elites that run the corporation and the public that funds it may lead to a loss of support in future.

This might be aided by the long campaign by anti-BBC cheerleaders such as Rupert Murdoch, and the corporation’s evident difficulties with diversity. The sight of Scottish independence supporters cancelling their licence fees two years ago to protest the BBC’s coverage of the referendum shows the risks. And there is a new danger to public-service broadcasting in the White Paper: the BBC will come under the control of broadcasting watchdog Ofcom – a creature whose “principal duty is to further the interests of citizens and of consumers, where appropriate by promoting competition”.

Democratising the corporation

A radical answer would be to use the process for renewing the BBC’s Royal Charter in December to do away with elite appointment and have a democratically elected BBC Trust instead. Drawing on the experience of newer and more representative forms of public ownership outside the UK, changing the governance structure could ensure that both consumers and the BBC’s other great neglected constituency – its workers – are properly represented.

A possible model could be to have one third of the board elected by licence payers; one third by the workforce; and the remaining third by government appointment. To ensure adequate geographical diversity, the government section might also have an element of representation from local and regional government. You would have fewer City grandees and more members of the general public and representatives from the UK’s regions. They could redetermine the corporation’s mission statement and values and bring a much more diverse range of experiences and knowledge.

The BBC would still have its independence and operational autonomy and be funded by the licence fee, but those who pay for it would now have proper ownership. The director general could still be a professional appointee with the right kind of managerial experience of running television and media enterprises.

Who knows if it would transform the corporation’s current output. I suspect you would see the BBC moving away from the increasingly narrow profit-driven commercial interests that characterise the corporate media, but either way the public would have helped choose. Look at what happened when the BBC listened to the Save 6 Music campaign and imagine that public representation being right at the heart of the corporation.

A democratic mandate would finally make it harder for future governments to undermine the BBC or remove the licence fee, and harder for the likes of Murdoch to criticise it – thereby helping to guarantee its independence. We live in an era where viewers vote constantly in reality TV shows. It is time we extended it to the people who oversee the BBC itself.

Andrew Cumbers receives funding from ESRC for a current research project 'Transforming Public Policy through Economic Democracy'.

Andrew Cumbers receives funding from ESRC for a current research project 'Transforming Public Policy through Economic Democracy'.

Andrew Cumbers, Professor of Regional Political Economy, University of Glasgow

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings