When the Reserve Bank board meets today for the first time this year it is likely to leave its cash rate unchanged at the current all-time low 0.75%.

Afterwards, it will announce its reasons, many of them good. But they’ve not always been good.

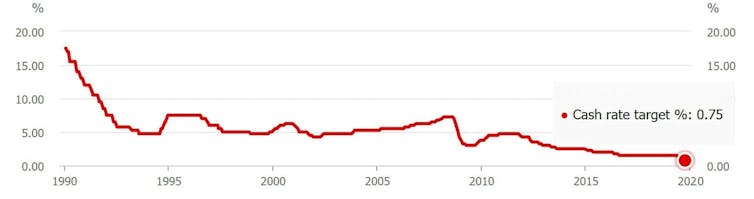

Reserve Bank cash rate

One with little to back it up was included in the minutes of the November meeting.

It said members “recognised the negative effects of lower interest rates on savers and confidence.”

Reserve Bank of Australia board minutes, November 2019

Similar claims have been made by members of the business community, especially bank executives whose profit margins are threatened by low interest rates.

For example, Westpac chief executive Brian Hartzer told a parliamentary committee in November that rate cuts were being seen as

a negative symbol rather than a positive symbol, in that they’re a sign that something’s wrong or that there’s a weakness in the economy

According to media reports, concern about the impact of cuts on confidence was a factor in the government’s decision to leave its agreement with the Reserve Bank on targets unchanged rather than strengthening it in order to more aggressively target inflation.

What’s the evidence?

The theory would be that even though interest rate cuts put more money in households’ pockets than they take out, the announcement that a cut is needed might convince householders that conditions are worse than they had thought.

In support of the proposition could be the coincidence that the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment dived to a four month low in October after the Reserve Bank cut, and then improved somewhat in November after it decided not to.

But more systematic study of the index by Melbourne Institute researchers Edda Claus and Viet Hoang Nguyen, finds that for the most part consumers respond positively to rate cuts and negatively to rate hikes, responding more to cuts than hikes.

My own research, forthcoming in the Australian Economic Review, also finds consumers correctly interpret rate hikes as a net negative for the economic outlook and rate cuts as a net positive. The response of businesses is more mixed.

The Reserve Bank’s own research finds that while declines in confidence following rate cuts are understandable given economic conditions are probably deteriorating, the cuts themselves moderate, not amplify the decline.

US studies reach similar conclusions. Research conducted for the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas found that a surprise 0.25 points hike in the Federal Funds led to an immediate 1 to 2 points deterioration in the University of Michigan index of consumer sentiment.

The authors of the Dallas Fed study note this means that consumers correctly interpret an increase in US official interest rates as negative for the economy, even if it might also be seen as signalling a stronger economic outlook.

When it comes to rate cuts, even so-called “unconventional monetary policy” of the kind underway in the US and being considered by Australia’s Reserve Bank, the authors found nothing in their study to suggest they harmed confidence.

And even if rate cuts did hurt confidence…

Of course, even if cuts in interest rates and unconventional monetary policy did harm confidence, that wouldn’t be an argument against them.

Were the Reserve Bank to hold off on acting on its assessment of the economy because it was concerned about about damaging confidence, the result would be higher-than-needed interest rates, which would themselves damage the economy.

The bank’s caution would backfire on it and those in the financial sector with a short-sighted focus on lending margins rather than the health of the economy.

Bank of Canada Holds Interest Rate at 2.25% Amid Trade and Global Uncertainty

Bank of Canada Holds Interest Rate at 2.25% Amid Trade and Global Uncertainty  U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains

U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Fed Governor Lisa Cook Warns Inflation Risks Remain as Rates Stay Steady

Fed Governor Lisa Cook Warns Inflation Risks Remain as Rates Stay Steady  India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out

India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out  South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom

South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom  Dollar Near Two-Week High as Stock Rout, AI Concerns and Global Events Drive Market Volatility

Dollar Near Two-Week High as Stock Rout, AI Concerns and Global Events Drive Market Volatility  Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient

Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient  Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure

Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure  RBI Holds Repo Rate at 5.25% as India’s Growth Outlook Strengthens After U.S. Trade Deal

RBI Holds Repo Rate at 5.25% as India’s Growth Outlook Strengthens After U.S. Trade Deal