On May 25, social media erupted with the image of a Black man once again whispering “I can’t breathe” while under the knee of a white police officer for eight minutes and forty six seconds. George Floyd’s death sparked horror, outrage — and familiarity.

Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin looked directly into the camera lens as he demonstrated to the world the full weight of white supremacy and the its impunity. Now that impunity is being challenged in the streets and in city halls in a call to defund, disband and rethink policing as we know it.

Disbanding is complex and does not mean eliminating police. Just as the call to “defund police” does not mean taking all money away from police. Each of these calls requires action and action is what we are seeing.

Minneapolis city council committed to disband the Minneapolis Police Department. City council president Lisa Bender said:

“It is clear that our system of policing is not keeping our communities safe … Our efforts at incremental reform have failed, period.” [The plan is to] “end policing as we know it and recreate systems that actually keep us safe.”

It does not mean the end of policing but rather an end to the Minneapolis Police in its current configuration. This has been done in California and New Jersey, with cities disbanding police departments and replacing them with new forces that cover entire counties.

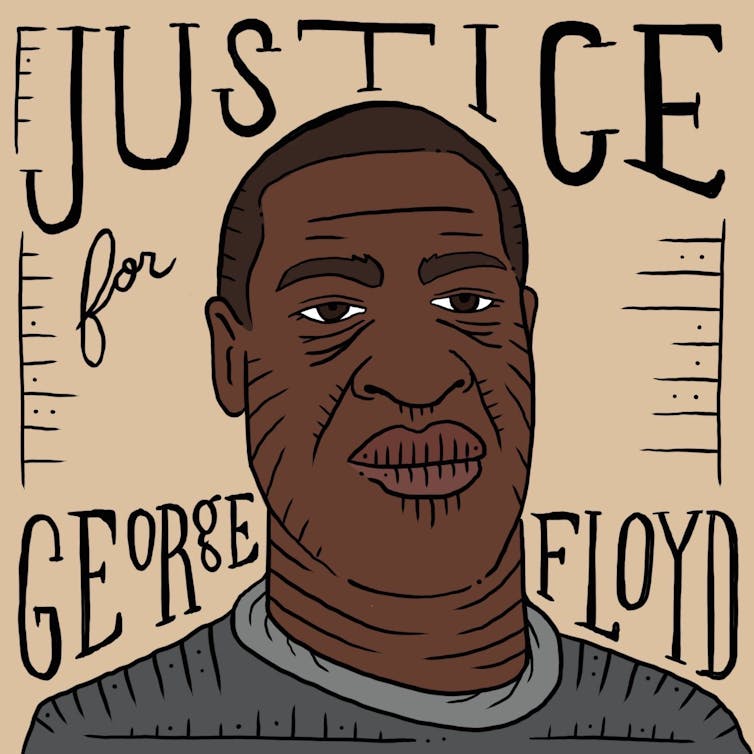

A memorial to George Floyd. (Dylan Miner), CC BY-NC

There are currently at least four major calls to defund police forces in Canada including in Edmonton, Toronto, Ottawa and Regina.

A brief history of defunding police

What does it mean to defund the police?

For some, defunding means a total cut to budget and getting rid of police. This can be classified as an abolitionist movement. As U.S. sociologist Alex Vitale explains in his book, The End of Policing, many of those movements can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s to the Black Panthers and others.

A protestor carries a sign calling for the Minneapolis Police Department to be defunded. (Koshu Kunii/Unsplash)

Their call for community safety was later taken up by others focused on prison abolition including Angela Davis. The call to abolish state violence and policing in exchange for direct democracy and mutual aid is the foundation of anarchism.

But for many others, the call to defund police is about defunding parts of policing. With that in mind, here are some places to rethink policing and police funding.

Move police out of schools

Kindergarten to Grade 12 students across North America have become accustomed to having police present at school through programming like school liaison officer, school resource officer or DARE programs (drug awareness). According to the American Civil Liberties Union, 1.7 million children in the U.S. attend a school with police present but without access to counsellors.

The school-to-prison pipeline refers to education and public safety policies that push students into the criminal legal system. (ACLU)

Police presence has been tied to the school-to-prison pipeline. It can negatively affect the experience of students, as schools have incrementally and increasingly taken on prison-like practices at the expense of student learning.

Following in the footsteps of University of Minnesota and the Minneapolis Public Schools, many places should consider moving police out of educational spaces.

The rise of the war cop

In the U.S., the militarization of police is directly tied to a sweeping set of reforms passed in the 1990s that led to a rise in war tactics against communities. This included a rise in programs that allowed police departments to receive war supplies.

This trend was then followed in Canada as arsenals and tactics have been used against Indigenous land and water defenders. Also, military tactics and SWAT response are often at the heart of new police practices during the execution of warrants.

In Louisville, Ky., a no-knock warrant led to the death of Breonna Taylor, an emergency medical technician. She was killed by police who raided her home in early March.

A review of police budgets allows for insight into how local law enforcement position themselves to residents. For example, in Regina, Sask., municipal police were tired of “borrowing” a tank from the RCMP so they sought the funds to buy their own. While there was resistance, this purchase was eventually approved.

Demilitarizing police comes first with taking away the arsenals they have acquired and then no longer funding the requests to enhance their arsenals.

Budgets

A police officer stands guard in New York’s Times Square. (Alec Favale/Unsplash)

In cities across North America, questions are being asked about how much money is spent on policing. In some bigger cities that amount could be as low as 25 per cent or upwards of 40 per cent of an entire city budget.

In Canada, policing is paid for through a combination of federal, territorial and local budget lines. In nearly all cities, the municipal police budgets are handled through city hall.

A review of most city budgets will demonstrate that policing takes up much of the budget line. Most years, police request an increase to account for ongoing changes to operating costs. What if this year and in the years to come, people said no to an increase and redirected those funds to community initiatives instead?

This is change that is doable. It would allow for much-needed funding to be redirected to community organizations.

A better future

We are seeing a reckoning as street protests continue and charges are being laid against the officers involved. We are also seeing a transformation in how people think about policing.

Assumptions about the role of police are being challenged and dismantled. Included in the critique is an intersectional lens and the ongoing role of white supremacy in racialized policing practices and policing Black lives.

People are rethinking policing and what it means for all members of our communities to be supported and safe. In other words: another world is possible when we defund and reimagine policing as we know it.

Michelle Stewart receives funding to support her research and community-based projects from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and Canadian Institutes of Health Research as well as Public Safety Canada for projects focused on criminal justice reform with attention to reconciliation in the justice system. She works for the University of Regina. Her comments are her own but are grounded in evidence and lived experiences that honour the ongoing impact of systemic racism, broken treaties, and settler colonialism.

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  Parents abused by their children often suffer in silence – specialist therapy is helping them find a voice

Parents abused by their children often suffer in silence – specialist therapy is helping them find a voice  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Yes, government influences wages – but not just in the way you might think

Yes, government influences wages – but not just in the way you might think  Stuck in a creativity slump at work? Here are some surprising ways to get your spark back

Stuck in a creativity slump at work? Here are some surprising ways to get your spark back  Locked up then locked out: how NZ’s bank rules make life for ex-prisoners even harder

Locked up then locked out: how NZ’s bank rules make life for ex-prisoners even harder  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  The ghost of Robodebt – Federal Court rules billions of dollars in welfare debts must be recalculated

The ghost of Robodebt – Federal Court rules billions of dollars in welfare debts must be recalculated  The pandemic is still disrupting young people’s careers

The pandemic is still disrupting young people’s careers  AI is driving down the price of knowledge – universities have to rethink what they offer

AI is driving down the price of knowledge – universities have to rethink what they offer