In Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders (1887), the trees sing.

Sometimes the sound is like a Gregorian chant, a threnody from the rustling leaves, the creaking boughs, the undulations of limbs heavy with leaves, swaying in the wind that rushes through the woods of Dorset’s Little Hintock.

At other times, it is a low moan, a cry of pain, voiced as if in sympathy with the tragic plight of the characters who wander through these woods, searching for something lost or never quite possessed – for a Hardyian character is always driven by a restive compulsion to move.

Even in stillness, Hardy limns the minute transformations of the body – of human limbs cicatriced with tree wounds, or the trunk of one of the forest’s oldest inhabitants – pulsing with life, desire, will.

These sylvan protagonists – English oaks, crab-apples, silver birches, willows, blackthorns, hazel trees, ash-trees, and elms – come into life with a sigh, an audible exhalation sounding from deep inside the trunk.

The vocabulary of trees

The Woodlanders tells the story of a small community who live and work in the forest. They are woodcutters and spar-makers, fruit-pickers and timber dealers, busily industrious under the tree canopy that makes a second sky.

Human labour keeps time with the seasons in Little Hintock, the fictive hamlet that Hardy maps onto the topography of Dorset in the south of England: felling timber in the autumn and winter; pressing apples for cider in the spring and summer. Hardy’s tragic hero, Giles Winterborne, is continually evoked by the traces of labour that cling to his skin, hair and clothes: apple pips and pomace, the vestiges of pulpy matter on his hands.

The bodies of the novel’s characters are expressive, not so much of their individual personality as their contact with the forest. Their flesh is imprinted with a history of woodwork unique to each. The skin is an index of mishaps with elms, boles, rubbings of bark and brushings of twig. These afflictions become the means through which the body is known, to the self and to others. Mnemonic aches and resisting joints are evocative of the past.

One of Hardy’s great themes, and an element of his aesthetic accomplishment that astonishes us still, is his unsettling of the individual, understood as sovereign, private and unified. Hardy understands the self as constituted by and continuous with both human and non-human others.

In The Woodlanders, the pliancy and impressible feeling of consciousness cannot be uncoupled from the botanic. We can see this – and hear it too – in the vocabulary of trees, which structures characters’ speech patterns and ways of thinking and being. Desires and passions are formed by the sculpting hand of the natural environment.

At times, the words characters speak to one another are felled like wood: in many of the novel’s climactic scenes, speech is painfully constrained, an inadequacy that is camouflaged by physical activity.

Winterborne suffers most acutely from this linguistic affliction. He finds his words cleaved “into two pieces”. They respond not to his conscious intentions, but instead, for instance, to the arc of his arm in the act of woodcutting. In this way, language is an effect of the body’s primacy: like an echo, it continually reasserts the fact of embodiment.

In an epoch of environmental catastrophe, The Woodlanders carries a new and startling urgency. The cumulative effect of the pervasiveness of trees is to imply something about our notions of selfhood, something that philosopher Dalia Nassar and plant scientist Margaret Barbour have described as the lesson trees can teach us about embodiment and boundedness, of “our rootedness, relationality, dialogue, and responsiveness”.

An English oak. Shutterstock

Attuned to the forest

The trees’ expirations are recorded by the two characters most lovingly attuned to the forest: Marty South and Giles Winterborne. In one remarkable scene, the pair – not quite lovers, yet united in a complicity that springs from their possession of a unique affinity with the vegetal world – plant fir saplings early one winter’s morning.

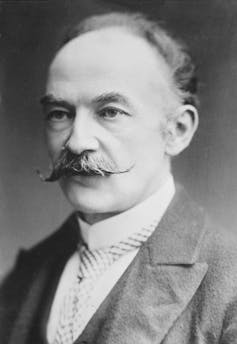

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928). Public domain.

Hardy’s affection for Winterborne is emphasised in the attention he pays to the young man’s movements. A skilled woodsman, Giles has a mystical ability. His fingers are “endowed with a gentle conjurer’s touch in spreading the roots of each little tree, resulting in a sort of caress, under which the delicate fibres all laid themselves out in their proper directions for growth”.

But it is the young woman Marty, barely more than a girl, with her hands roughened by the skin of trees, who can hear them “soughing”. Hardy lets us hear it, too, with that lovely word. Placing the plant in the cavity of soil Giles has made, Marty listens as “the soft musical breathing instantly set in, which was not to cease night or day till the grown tree should be felled”.

Marty’s percipience indicates her prophetic role in the story. She sees and hears the signs of imminent tragedy long before the other inhabitants of the village.

There is more to this relationship between humans and trees, something of ontological significance that Hardy realises about our embeddedness in the environment. Hardy does not think about people without reference to the natural world. Put another way, and somewhat awkwardly, there is no character without tree. There is no human voice, nor human love or pain, that is not articulated without this defining correspondence with fecund and fleshly matter.

The human drama that reaches such a fine pitch of poignancy in The Woodlanders arises from the moist soil and the branches burdened with gratuitous leaves “rubbing each other into wounds”. The diffuse vocabulary of nature, tender and violent, is absorbed into the representation of human emotion. When Grace realises that she is in love with Giles more deeply and irretrievably than she had first understood, her “heart [rises] from its sadness like a released bough”.

Rufus Sewell as Giles Winterbourne and Emily Woof as Grace Melbury in the 1997 film adaptation of The Woodlanders. IMDB

In Hardy’s radical cosmology, to be in love is to yearn for metamorphosis: a poetic and fantastical transposition of metaphysical desire into the earthy and sap-stained realm of the trees.

While Hardy’s prose vibrates with nature’s energies, a competing and, at times, antagonistic temporal order regulates social life. Obsessions with patriachal lineage and class define the elaborate marriage plot, which concerns five characters: Grace Melbury and Winterborne, natives of Hintock, who have been affianced since late childhood; Edred Fitzpiers, an urbane and brilliant doctor, who becomes Grace’s feckless husband; and Fitzpiers’ lover, Felice Charmond, a widowed woman, indulgent in her love, yet capricious in her affections.

The last is Marty South, who watches the romantic entanglements from afar, intervening when necessary, usually by recourse to a tool from the forest itself.

Arcadian lovers

The skein of secrets, lies and betrayals that binds the characters is too complex to detail here, so I will concentrate on the couple who absorb Hardy’s and the reader’s interest: Grace and Giles, the Arcadian lovers, whose quietly magnificent passion for each other is inextricable from the brilliancy and pain of the forest. It is in his depiction of their acts of tenderness, culminating in a spirit of mutual worship that marks their love for one another, that Hardy most fully realises an arboreal sublime.

Hardy’s fiction is notorious for its tragic spirit, distilled so that it is almost unbearable. Suffering seams even the rare moments of bliss in his stories.

In The Woodlanders, this tragic spirit is depicted in the extraordinary encounter between Giles and Grace, staged as a slowly unfolding lovemaking, but of a very different kind. As the narrative draws ineluctably toward the despair that has been everywhere foretold, Grace and her lover descend into a Dantean underworld of dense plantations, a world so thick with foliage that it feels unmoored, belonging only to these two.

Eroticism takes place not by actual lovemaking, but through small gestures, touches of fingertips, the sharing of food, bare words spoken. As Grace realises Winterborne is dying, her transformation into woodland myth is complete. Dragging his feverish body on a barque of ferns and sticks, she brings him to a place of warmth. Sheltered from the incessant rain, she kisses and bathes his too-warm flesh, tending to him with all the solicitousness that she has until now feared to give.

The path to Thomas Hardy’s cottage in Dorset, England. Wikimedia Commons

In these ritualised acts of love for a dying man, we see Hardy’s ideal of love. It is spiritual rather than carnal, but not a simple opposition. It is, rather, a dialectic between the ideal and the fleshy. The lovers “trouble each other’s souls”, but it is a yearning grounded in the material.

We see this when Winterborne dies, just hours after Grace’s desperate attempts to revive him, to keep him with her. Walking through the forest toward her father’s house, and toward her rueful husband, the world is changed. The trees mourn for Winterborne, weeping sap that is a phosphorescence, a milky substance that catches the weak light tenacious enough to penetrate the canopy. Giles has become “her wood-God, smeared with lichen”, the very milieu in which she moves.

The Woodlanders is as devastating as it is extraordinary in its beauty. One doesn’t so much read Hardy, in the sense of following the black marks upon the page, as experience the world he creates.

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings