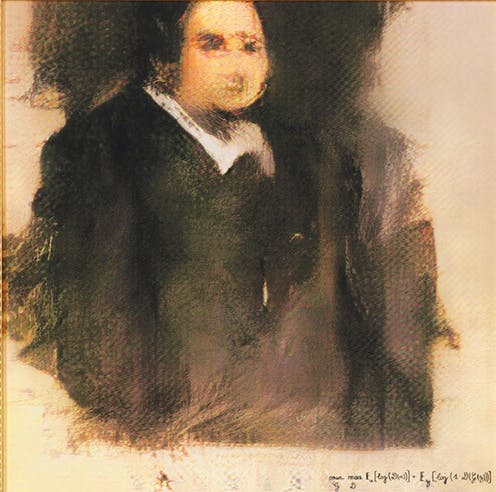

Last fall, an AI-generated portrait rocked the art world selling for a staggering US$432,500 at Christie’s auction house in New York. The portrait called “Edmond de Belamy” features a slightly out-of-focus man with no nose and a blob for a mouth, dressed in what seems to be a dark frock-coat over a white-collared shirt.

From a distance, the 70 cm by 70 cm portrait printed on canvas and hung in a gilded wood frame, looks like it belongs in a museum of classical art. But upon closer inspection, the artist’s signature — the mathematical formula that created it (min G max D x [log (D(x))] + z [log (1 – D (G(z)))]) — reveals that the artist was not human.

With this astonishing achievement, we seemed poised to usher in art’s next medium — and possibly even to redefine what it means to be an artist. But in November 2019, another in the Belamy series, “La Baronne de Belamy,” sold at Sotheby’s without the same success. “La Baronne” sold for only US$25,000, just slightly more than its estimated value. Has the AI art bubble burst?

What is AI art?

The Belamy series was created via machine learning by the Paris-based arts collective known as “Obvious.” They fed thousands of portraits into an algorithm, effectively teaching the machine portraiture techniques of the 18th century. The result was a series of 11 images known as the fictional “La Famille de Belamy.”

Like the girl in Johannes Vermeer’s famous painting, “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” Edmond de Belamy does not exist. The painting instead is a “tronie,” which is derived from the Dutch word for face. A tronie exists only in the artist’s imagination. There is no story behind the painting — no wealthy member of society being immortalized on canvas, no scandal surrounding it and not even admiration for the subject of the portrait. It is the viewer’s imagination, which is forced to start afresh, that makes interpretations about what is being viewed.

In the case of “Edmond de Belamy,” it is more complicated. It is not the work of the artist’s imagination, but in fact, the work of the algorithm’s “imagination.” “Edmond de Belamy” is work of art captured by the “mind” of an artist that is not human.

Girl with a Pearl Earring (circa 1665) is a painting by Johannes Vermeer. (Johannes Vermeer)

Algorithm vs algorithm

The machine learning system used to create the Belamy series is a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Essentially, it is a system that pits algorithms against each other in order to improve the quality of the results.

One algorithm generates data and the other competes with it, discriminating between the real and false data being produced. The entire system is described as “adversarial.”

GANs were first created in 2014 by Ian Goodfellow, a computer scientist. In a salute to Goodfellow, Obvious translated his name to be used for their series of art: good and fellow translate roughly into French as “bel ami” hence, Belamy.

But, is this really art?

GANs present us with an entirely new way of understanding art, which was once exclusively the domain of human beings. And while its products and processes may prove to be beneficial, this type of art blurs the distinction between humans and machines, raising ethical, regulatory and process conundrums in society. Can an AI be an artist? And if so, what is an artist? Or is the AI simply a tool, like a paintbrush?

Proponents of AI art see its worth not only in the end product of what it creates, like “Edmond de Belamy,” but also in the process of creating the artwork. So, for example, is the Belamy series a collaboration of artist and machine exploring new visual forms? This is not unlike the form of conceptual art where the idea behind the work and the process of creating it is more important than the outcome.

Further, if we do consider it to be art, who — or what — has the right to the art it creates? The AI itself? The group that owns the AI, like Obvious? Or the coder of the algorithm?

‘La Baronne de Belamy’ is a painting created by Ai to look like work by an 18th century painter. Obvious

This question arose, in fact, with the success of “Edmond de Belamy.” While Obvious claimed responsibility for the 11 portraits in the Belamy series, a teenager developed the code responsible for the series.

Robbie Barrat, at the age of 17, started experimenting with AI and art, and uploaded the code he had used to make paintings to GitHub, a code-sharing platform that enabled others to download and learn from it.

Obvious has never denied that their work has relied on others — a fact evident in their homage to Goodfellow (“bel ami”) and also in acknowledging the work of Robbie Barrat on their website. But it raises more questions about the right to the artwork and where we should draw the line.

The AI art bubble may have burst, but the questions of what is art and who is the artist raised by AI art remain.

Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev: Blockchain Can Open Private Markets to Retail Investors

Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev: Blockchain Can Open Private Markets to Retail Investors  Crypto Investment Platforms eToro and M2 Granted Approvals to Operate in the UAE

Crypto Investment Platforms eToro and M2 Granted Approvals to Operate in the UAE  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  Wizards of the Coast Balances High-Level Play in Final 5th Edition Dungeons & Dragons Campaign

Wizards of the Coast Balances High-Level Play in Final 5th Edition Dungeons & Dragons Campaign  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Elon Musk’s X Money Launch Set to Revolutionize Digital Payments and Dominate 2025’s Fintech World

Elon Musk’s X Money Launch Set to Revolutionize Digital Payments and Dominate 2025’s Fintech World  Paytm Shares Plummet as Regulatory Crackdown Takes Toll

Paytm Shares Plummet as Regulatory Crackdown Takes Toll  Visa Launches Global AI Advisory Practice to Unlock the Potential of AI in Payments

Visa Launches Global AI Advisory Practice to Unlock the Potential of AI in Payments  Robinhood Announces Plans to Expand Stock-Exchange Application to U.K.

Robinhood Announces Plans to Expand Stock-Exchange Application to U.K.  Mastercard Partners with MoonPay to Unlock Web3 Capabilities in Experiential Marketing

Mastercard Partners with MoonPay to Unlock Web3 Capabilities in Experiential Marketing