Innovation is not all sunshine and frolicking lambs.

Innovation has real costs — monetary, psychological, intellectual and effort-based — that need to be addressed or mitigated if you want people to actually innovate.

There’s an archetype in media that destruction and upheaval brings out the best ideas and creates jobs. In literature and in society, upheaval, necessity and desperation are portrayed as the prime motivators of innovative behaviour. The problem is that outside of soap operas and medical dramas, people usually have something to lose.

But my research has led me to nuance this idea. Yes, people are more willing to take chances when something bad happens. Yes, disruption results in innovation; But to be more precise, studies, including my own, show that stability results in more innovation than disruption would.

Improvisation is not innovation

There is a reason why Fortune 500 companies don’t run their HR departments like an elimination game show, although that might make the average staff meeting significantly more interesting. The fact is that upheaval and desperation do not mitigate the costs of innovating; chances are they only make costs more punishing.

At best, desperation and upheaval might induce unity within like minded-groups and force a pragmatic solution to a particularly important challenge. But such a scenario conflates improvisation with innovation.

Improvisation is a quick solution to a presented challenge, whereas innovation encompasses more than the present moment. There are links between the two, but they tend to have different goals. Innovation can be methodical, reflective and address challenges that are not widely perceived.

My research has shown me the face of an under-hyped insight: being methodical and reflective is not fostered by high-pressure, desperate circumstances.

Through 30 in-depth interviews, two literature reviews integrating the findings of 91 peer-reviewed articles and 500 survey responses, I conclude disruption does not always drive the most monumental or ingenious innovation. People don’t write great poetry while running from wolves, but they might discover their unexpected and useful talent for tree climbing.

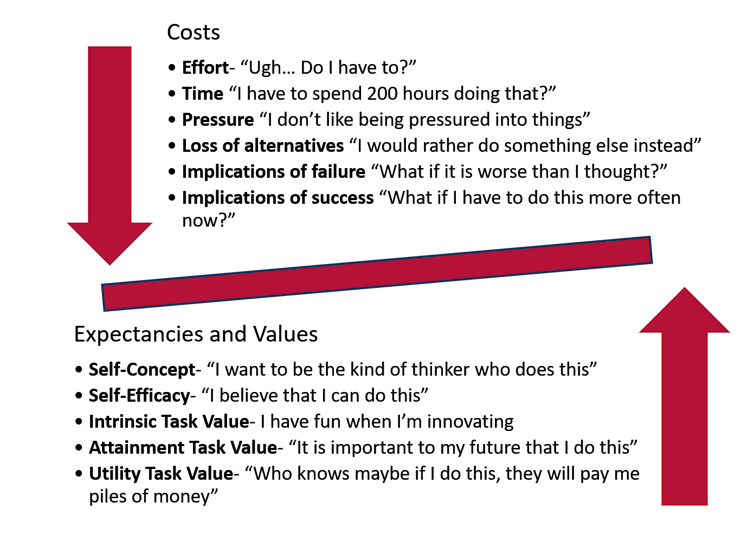

Rather, the motivation to innovate is a function of what psychology and management theorists call “expectancies” (expectations of success based on confidence and past experience). It’s also grounded in “task values”: desires for fun, one’s interests, identity fulfilment or usability elsewhere in a person’s life. These positive motivation factors are are in tension with the perceived costs of innovating (financial, psychological, loss of alternatives, implications for success and for failure).

Consider the figure below: It depicts the motivation to innovate as a balancing act between expectancies and values which increase the motivation to innovate, while costs decrease the motivation to innovate.

EVC Scales Adapted from Soleas (2018)

When I asked innovators their major motivation, one respondent from a sample of 500 said their primary driver was monetary. The rest described a mixture of two scenarios: innovating is fun and/or important to their identity or to society.

With this emerging research in mind, there would be at least two strategies to motivating innovative behaviour: the most straightforward is to try to increase the values and expectancies of innovators to strengthen the positive factors making innovative behaviour more likely. This can be done through incentives like rewards, letting people pursue their ideas, letting people have fun with their ideas, and structured, systematic programs that build up experiences.

A second approach would be to actively mitigate the costs, so that the costs don’t detract from the forces motivating innovation. Such an approach is what I’d like to call a proactive motivation loss-prevention (PMLP) approach.

Stability and Safety

There is a common thought that innovation is disruptive by its nature. There are situations where that’s true: For example, the impact of electricity on chandlers (people who made candles); how the use of social media has changed formal and legible English. These are vivid examples that capture attention, but they don’t tell the whole, or even most, of the story.

The scientist Matti Pihlajamaa recommended that teams be composed of innovators and non-innovators in a hammer and anvil model, where innovators strike ideas and non-innovators provide support and stability. Stability lets people establish a rhythm and, frankly, have a life. That’s why orchestras have conductors and we have a work day.

“Large and in-charge”

Much like stability, safety is also a concern that needs to be managed by people who wish to stoke innovation. One of my interviewees told me:

“The status quo is large and in charge … If you don’t manage change intelligently it will run you over and laugh about it.”

He was right — when you innovate, you confront the momentum of history. It’s best to do that from a protected position with peers that support you.

Industrial relations experts Bruce Curran and Scott Walsworth found that pay-for-performance or high salaries were ineffectual in stoking employees’ motivation to innovate, whereas indirect pay such as healthcare benefits, job security or child care significantly increased motivation to innovate. Other researchers have reported similar findings.

A sense of stability can free up creative energy. CC BY

Stability and safety are cost mitigation tactics that do diminish costs, thus freeing up interest, fulfillment, confidence and past experience to work their magic and promote innovative behaviour. This works because you’ve taken other costs off employees’ plates; you’ve let them focus on the tasks at hand. The post-it note inventor at 3M came up with the idea during “15 per cent time,” when, while being paid, employees could develop their own ideas.

That’s right managers and leaders: forget releasing wolves into your workplace to spark innovation. It’s probably better to borrow lambs from a petting zoo. It turns out that optimizing your environment for stability and well-being, rather than disruption, makes innovation more likely.

Global PC Makers Eye Chinese Memory Chip Suppliers Amid Ongoing Supply Crunch

Global PC Makers Eye Chinese Memory Chip Suppliers Amid Ongoing Supply Crunch  Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine

Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine  OpenAI Expands Enterprise AI Strategy With Major Hiring Push Ahead of New Business Offering

OpenAI Expands Enterprise AI Strategy With Major Hiring Push Ahead of New Business Offering  Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users

Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users  Nintendo Shares Slide After Earnings Miss Raises Switch 2 Margin Concerns

Nintendo Shares Slide After Earnings Miss Raises Switch 2 Margin Concerns  Amazon Stock Rebounds After Earnings as $200B Capex Plan Sparks AI Spending Debate

Amazon Stock Rebounds After Earnings as $200B Capex Plan Sparks AI Spending Debate  Tencent Shares Slide After WeChat Restricts YuanBao AI Promotional Links

Tencent Shares Slide After WeChat Restricts YuanBao AI Promotional Links  Jensen Huang Urges Taiwan Suppliers to Boost AI Chip Production Amid Surging Demand

Jensen Huang Urges Taiwan Suppliers to Boost AI Chip Production Amid Surging Demand