Zhuangzi – also known as Zhuang Zhou or Master Zhuang – was a Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE. He is traditionally credited as the author of the ancient Taoist masterpiece bearing his name, the Zhuangzi.

The work of Zhuangzi has been described as “humorous and deadly serious, lighthearted and morbid, precisely argued and intentionally confusing”. On the surface, his teachings can seem outright nonsensical. He maintains that “listening stops with the ear”, that we should “hide the world in the world”, and that a person on the right path is “walking two roads”.

But Zhuangzi delights in paradox. His philosophy deliberately toys with words to reveal that language itself is the foremost barrier in our search for our essential selves and our desire to live happy, fulfilled lives.

For Zhuangzi, words hold everything that is extraneous to our essential selves:

The fish trap exists because of the fish. Once you’ve gotten the fish you can forget the trap. The rabbit snare exists because of the rabbit. Once you’ve gotten the rabbit, you can forget the snare. Words exist because of meaning. Once you’ve gotten the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find a man who has forgotten words so I can have a word with him?

Words are like vessels for conventional distinctions and values we inherit from the past. But language, as the bearer of social ideals and expectations, becomes the source of the irresolution, trouble and anguish that denies us our contentment and tranquillity.

Sharing the view expressed in Laozi’s Tao Te Ching, Zhuangzi argues that we must first be disorientated by language to discover that higher knowledge is beyond words.

The Hundred Schools of Thought

Zhuangzi was a harsh critic of the dominant and demanding ideals of his time.

What is known as the Golden Age of Chinese Philosophy lasted from the sixth to the third century BCE in the period of the Zhou dynasty. The flourishing of different philosophical views during that time is known as the Hundred Schools of Thought.

Intellectual society existed to guide society and its rulers towards the Way (also known as the Tao) – the central concept and practical feature of Taoism.

The two dominant schools of the Hundred Schools of Thought were Confucianism and Mohism. Broadly speaking, Confucianism centralises ritual propriety and familial piety as just some of the necessary virtues of the “gentleman” – that is, the upstanding and model citizen or ruler.

The Mohists were critical of the Confucians. They advocated a calculated impartiality in our distribution of care – a view in many ways reminiscent of what the West would later term “utilitarianism”.

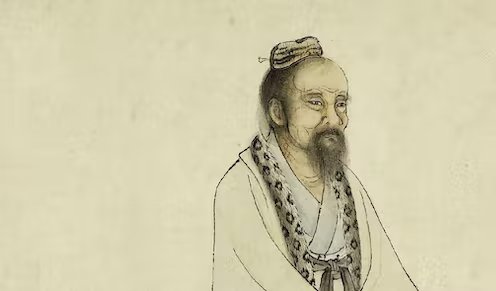

Image of Confucius c.1770. Artist unknown. Public domain

A common critique of Confucianism is that it places too much emphasis on social order through rituals and hierarchies. One could argue, with respect to the Mohists, that too much emphasis is placed on establishing a universal moral principle in a way that risks overlooking the complex features of our individual moral lives.

Zhuangzi opposed the full spectrum of such views, supposing instead that being persuaded by the Confucians or the Mohists, for example, depended largely on one’s individual perspective. Traditions and schools of thought set transcendental ideals, which risk drawing our souls out of us in their quest for righteousness and truth.

For Zhuangzi, what really matters is that we maintain a sensible, sceptical distance from conventional distinctions and resist committing to any one specific worldview.

Right is not right; so is not so. If right were really right, it would differ so clearly from not right that there would be no need for argument. If so were really so, it would differ so clearly from not so that there would be no need for argument. Forget the years; forget distinctions. Leap into the boundless and make it your home!

Adopting a healthy scepticism towards inherited ideas means “emptying the container of the Self”, or perhaps exercising a kind of trained “forgetting” of that which is extraneous to the essential self. In this state, we become less prone to partaking in the superfluous occupations we impose upon ourselves to cope with the weight of social expectations.

This is what Zhuangzi means when he argues that we must train our ability to be in and not of the world.

So the sage wanders in what exists everywhere and can’t be lost. He likes growing old and he likes dying young. He likes the beginning and he likes the end.

We should not be overly sceptical, however. “Words are not just blowing wind.” We must simply remember that words “have something to say” and that language is only a repository for meanings, not meaning itself.

In the same way, Zhuangzi argues that we cannot deny we are social animals. Certain duties are inescapable features of the roles in which we find ourselves. To be in the world and not of it means we accept what is beyond our control with equanimity.

Zhuangzi’s Butterfly Dream (c.1550). Public domain

Theraputic skepticism and the butterfly dream

Zhuangzi’s most celebrated parable is about a dream:

Once upon a time, I, Zhuangzi, dreamt I was a butterfly, fluttering hither and thither, to all intents and purposes a butterfly. I was conscious only of my happiness as a butterfly, unaware that I was Zhuangzi. Soon I awakened, and there I was, veritably myself again. Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man.

In entertaining for a moment the idea that we might be dreaming we are a butterfly that is dreaming it is human, we engage in the very activity which allows us to break free of the normal and human way of understanding the world. This is a kind of therapeutic scepticism.

The adoption of this more universal perspective makes our understanding more holistic and more exciting. With practice, our ordinary lives can become imbued with moments of spontaneous awe. We can learn to see the transformation of things – how everything eventually becomes part of something else. In questioning the world around us, we transcend our own limited perspective and ignite a boundless curiosity about everything in the cosmos.

In the 20th century, the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch described the highest virtue necessary for living a fulfilled life as a kind of “unselfing”.

“Good is a transcendent reality,” she wrote, and unselfing, or engaging in this therapeutic act of scepticism, allows us to “pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is”.

Zhuangzi and Murdoch might agree that our ability to transcend our human perspective – to see the world as a butterfly – just is what makes us human. We can find our essential selves when we are open to our vast capacity for imagination and creativity. We can free ourselves of the distinctions, ideas and traditions that become imprisoned in the words we use.

A final thought: perhaps Zhuangzi is best left uninterpreted. I will leave you with a line which, for me, is reminiscent of the Gadfly of Athens, Socrates, and his desire for knowledge. But what it really means is up to you:

People all seek to know what they do not know yet; they ought rather to seek to know what they know already.

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate