20 years have passed since the Aceh tsunami, which left deep scars on Indonesia, especially for those directly affected. Aceh was also recovering from a three-decade armed conflict between the Free Aceh Movement and the national government

Throughout December 2024, The Conversation Indonesia, in collaboration with academics, is publishing a special edition honouring the 20 years of efforts to rebuild Aceh. We hope this series of articles preserves our collective memory while inspiring reflection on the journey of recovery and peace in the land of ‘Serambi Makkah.’

Sunday, December 26, 2004, 7:58:53 AM (WIB, GMT+7): A 9.1 moment magnitude (Mw) earthquake occurred off the west coast of Aceh. The quake, originating from a depth of 30 kilometers below the sea, triggered a tsunami that devastated the province.

Research in 2021 suggested the earthquake’s magnitude was actually greater than what was previously recorded — 9.2 Mw. Scientists came to this conclusion after recalculating tsunami data using Green’s Function, a mathematical method that analyses how tsunami waves are formed and spread. This gave them a more accurate estimate of how strong the earthquake was.

From December 26, 2004, to February 26, 2005, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) documented about 2,050 aftershocks, a series of aftershock caused by the mainshock.

The effects of the 2004 Aceh earthquake and tsunami extended beyond Indonesia, affecting coastlines in Southeast Asia, South Asia, and possibly Africa. More than 227,000 people were killed, with Aceh alone accounting for approximately 167,000.

The 2004 Aceh Earthquake and Tsunami is known as one of the most devastating natural disasters in history. While it left deep wounds, it also demonstrated the fundamental need for disaster preparedness.

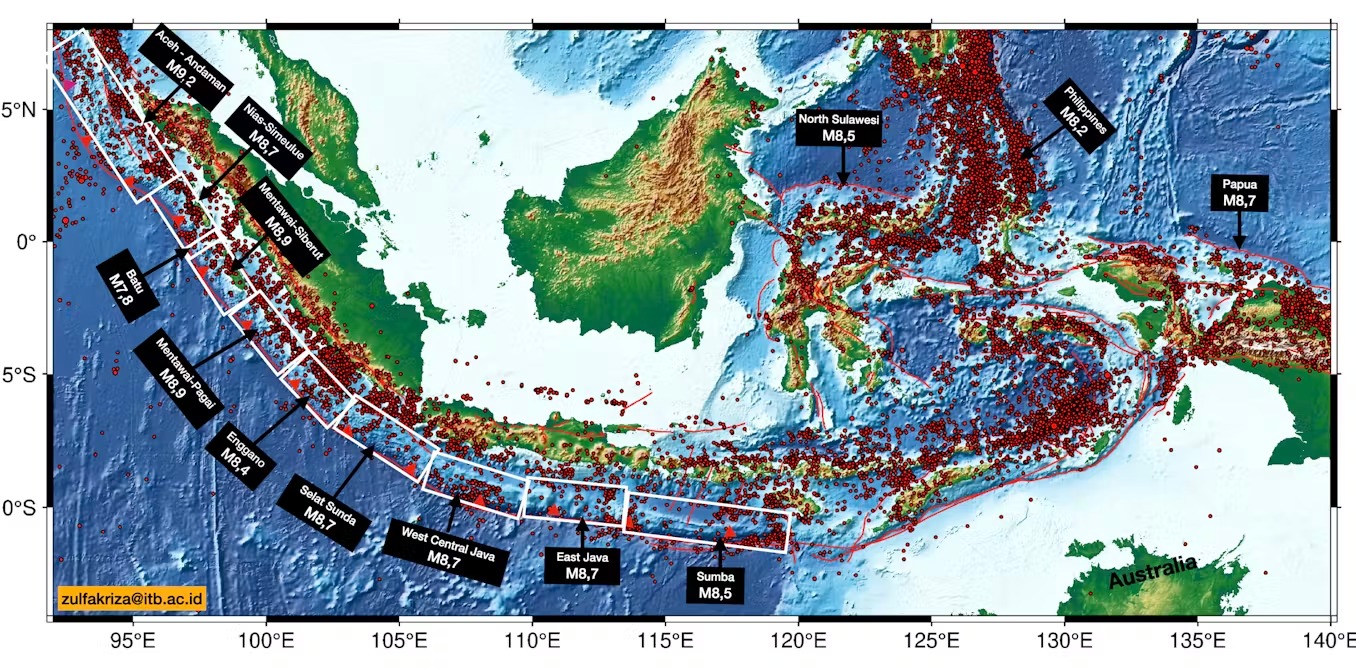

Tectonic map, megathrust zones, and seismic gaps

Indonesia is prone to disasters due to its location in a tectonically active zone where four major plates — Indo-Australian, Eurasian, Pacific, and Philippine — with convergence movement.

Comprising Earth’s rigid outer layer or lithosphere, a tectonic plate is a large, irregularly shaped sheet of solid rock that moves and interacts with other plates to sculpt the surface of the planet over geological time. These plate clashes have the potential to trigger massive earthquakes, particularly in western Sumatra, southern Java, Bali, Nusa Tenggara, the Banda Sea, Maluku, Papua, and Sulawesi.

A shift between two tectonic plates in the Indian Ocean resulted in a thrust fault, causing the 2004 Aceh earthquake. The fault stretched 500 kilometers – roughly the distance between Jakarta and Yogyakarta – with a breadth of about 150 kilometers. Known as a “megathrust earthquake,” the plates shifted by more than 20 meters, releasing enormous energy and causing tsunami waves up to 35 meters high – the height of a 10-story building.

Aside from earthquakes and tsunamis, tectonic movements can also trigger volcanic activity. Indonesia, which is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, has 127 active volcanoes, making it the world’s most seismically and volcanically active region.

Between 1900 and 2023, Indonesia recorded 14,820 earthquakes with magnitudes greater than 5 Mw. Among these, 15 were more than 8 Mw, including the 2004 Aceh earthquake. Other big earthquakes, like those in Sumba (1977), Biak (1996), Nias (2005), and Bengkulu (2007), also triggered tsunamis, causing substantial casualties and damage.

Indonesia also has several megathrust zones – areas along tectonic plate boundaries prone to generating large earthquakes like the 2004 Aceh event. There are 13 identified megathrust zones near the waters off western Sumatra, southern Java, Bali, Nusa Tenggara, northern Sulawesi, Halmahera, and Papua. These zones are prone to generate quakes of magnitudes ranging from 7.8 to 9.2 Mw, capable of delivering major destruction and tsunamis.

Over the last 30 years, some of Indonesia’s megathrust zones have been releasing seismic energy. These zones were the source of major earthquakes such as 1996 Biak, 1994 Banyuwangi, 2004 Aceh, 2005 Nias, 2006 Pangandaran, and 2007 Bengkulu.

However, data from the past 123 years show that some parts of the megathrust zones rarely experience large earthquakes. This could be because tectonic movements in these locations are stuck, causing stress to build up over time. These “seismic gaps” indicate high-risk zones for future big earthquakes.

A seismic gap, for example, exists between the megathrust zones off the western and eastern coasts of Java. For instance, in western Java’s subduction zone, the slip deficit — or plate movement locked in place — has reached 40-60 mm per year. If this energy is eventually released, it might result in a significant earthquake and possibly a tsunami.

Advances in disaster research

Indonesia’s high disaster risk has attracted scholars from all around the world, particularly following the 2004 Aceh Tsunami. From 2005 to 2024, Google Scholar recorded approximately 1,000 scientific works on Indonesian earthquakes and tsunamis.

These studies have improved our understanding of earthquake causes and trends. For example, research on the 2018 Palu and Sunda Strait tsunamis revealed that neither was directly caused by earthquakes. The Palu tsunami resulted from an undersea landslide triggered by a 7.5 Mw earthquake on September 28, 2018. Meanwhile, the Sunda Strait tsunami was caused by the fall of Mount Anak Krakatau’s volcanic side.

Indonesian academics have also investigated big earthquake origins and aftershocks. Teams from the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), the Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency (BMKG), and the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) have looked at aftershock patterns to learn more about where earthquakes come from and how they work. Among those closely studied are 2018 Lombok and 2022 Cianjur. This has led to new ideas for reducing risk and damage.

The Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning System (InaTEWS), managed by BMKG, continues to encourage seismic research collaborations. By 2024, the system would have 521 seismic stations spread across Indonesia. This extensive network allows for faster broadcast of earthquake data to the public, notably timely tsunami warnings after major earthquakes.

Mitigation requires collaboration

While scientists continue to investigate tectonic motions, accurately predicting earthquakes and tsunamis remains impossible. Therefore, mitigation and risk reduction are crucial.

Disaster mitigation efforts include public education and the use of earthquake-resistant infrastructure. These require the support of a wide range of stakeholders.

In 2007, three years after the Aceh Tsunami, Indonesia passed a Disaster Management Law, detailing risk reduction activities, including mitigation. This law promotes collaboration among five major elements: government, communities, academics, corporations, and the media — a framework known as the “pentahelix.”

The government acts as a regulator, the media disseminates information, corporations provide financial and technological support, communities serve as field implementers, and academics act as innovators.

Collaboration is essential for successful catastrophe mitigation. However, problems such as sectoral ego frequently impede efforts. For example, a refusal to share data across authorities can jeopardise earthquake research and mitigation efforts.

Finally, disaster risk mitigation is a shared responsibility. Building a more robust and sustainable mitigation system requires improved institutional coordination and communication.

As the Black Summer megafires neared, people rallied to save wildlife and domestic animals. But it came at a real cost

As the Black Summer megafires neared, people rallied to save wildlife and domestic animals. But it came at a real cost  Ukraine minerals deal: the idea that natural resource extraction can build peace has been around for decades

Ukraine minerals deal: the idea that natural resource extraction can build peace has been around for decades  How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus

How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus  What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains

What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains  LA fires: Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke is poorly understood − and a growing risk

LA fires: Long-term exposure to wildfire smoke is poorly understood − and a growing risk  GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’

GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’  Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research

Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research  Rise of the Zombie Bugs takes readers on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world

Rise of the Zombie Bugs takes readers on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world  The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer  Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history

Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history  Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys

Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys  Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate

Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate  Burkina Faso and Mali’s fabulous flora: new plant life record released

Burkina Faso and Mali’s fabulous flora: new plant life record released