Editor’s note: Below is an edited account from the forthcoming book, ‘White Riot: The 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver,’ by Henry Tsang (Arsenal Pulp Press).

On Sept. 7, 1907, a crowd gathered at 7 p.m. at the Cambie Street Grounds, now known as Larwill Park in downtown Vancouver. Led by Major E. Brown from the British Columbia Regiment at the Beatty Street Drill Hall, a cavalcade, made up of labour and church leaders and Mayor Alexander Bethune and his wife, Catherine, was accompanied by 5,000 people, many waving white banners reading, “A White Canada for Us.” They proceeded downtown toward city hall.

The event was organized by the conservative Asiatic Exclusion League, founded just months before by the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council. The mayor and several city councillors were founding members, along with many Christian leaders. Its first meeting was held on Aug. 12 and attended by 400 white men.

The league was modelled after the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League in San Francisco and many others like it along the West Coast. These groups advocated for a “white man’s country” and the prohibition of Asian labour, to be achieved through legislation and, if necessary, violence. A resolution calling on the federal government to exclude Asians from Canada was enthusiastically passed by the newly formed organization.

By the time the group reached city hall, many more thousands had joined in. Estimates of the crowd range from 25,000 to 30,000 people — over a third of the city’s population at the time. Guest speakers included clergymen, lawyers, politicians and anti-Asian activists from New Zealand and the United States.

As the rally grew, an angry mob formed; and marched toward Chinatown. The people there were initially taken by surprise. But they began to organize and to fight back. The Daily Province reported that, “the Chinese armed themselves as soon as the gun stores opened. Hundreds of revolvers and thousands of rounds of ammunition were sold before the police stepped in and requested that no further sale be made to Asians.”

Police could not contain the mob

The police force called in all of their off-duty officers, totalling about two dozen. The fire brigade was also called in to help. Badly outnumbered, they were unable to have any impact.

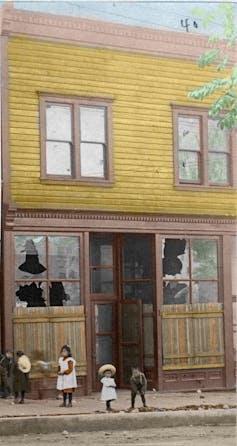

A colourized photo of Shanghai Alley after the Chinatown riots in 1907. 360 Riot Walk/Philip Timms/ University of British Columbia Library, Chung Collection, Vancouver, CC-PH-10626, Author provided

Although there were no documented deaths due to the riots, there were close calls. Arrests were few, in part because the crowd would rescue anyone captured. Only five rioters were eventually found guilty and given jail terms of one to six months.

The local English-language press blamed American labour leaders for inciting the riot. However, local Chinese-language newspapers placed the blame on white unions, most of which were involved in anti-Asian activism and provocation.

The rioters encountered resistance

On late Sunday afternoon, the rioters regrouped to attack the Japanese residents, who had almost a full day’s warning to prepare for the attack.

They stockpiled bricks and rocks to throw at the rioters and armed themselves with guns and knives. Hand-to-hand combat took place on the streets. From rooftops, rocks, bricks, bottles and blocks of wood were thrown at the rioters, who made it as far as the Powell Street Grounds (now Oppenheimer Park).

The mob did not expect such resistance, nor the escalating number of casualties.

Colourized image of 122 Powell St., 1907. from 360 Riot Walk/Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, PA-067275, Author provided

By Monday morning, the riots had died down, in part due to heavy rains. The Chinese Benevolent Association and clan associations organized a general strike that continued until Wednesday morning, shutting down many parts of Vancouver, including the sawmills and a third of the restaurants.

The Japanese went to work Monday, but left in the afternoon to attend a public meeting at the Powell Street Grounds to demand reparation from the city. Mayor Bethune came to address the crowd’s concerns — ironic, given that he was one of the Asiatic Exclusion League’s co-founders.

A federal inquiry and demands for compensation

The Japanese and Chinese communities petitioned the federal government to pay for damages.

Ottawa sent the federal deputy minister of labour, William Lyon Mackenzie King, to conduct a Royal Commission inquiry.

Pressure applied to England by Japan resulted in a swift response, with over $9,000 in settlement for damages. Compensation for the Chinese was slower, as they lacked the political support of an up-and-coming nation, but eventually the compensation was almost $27,000.

King’s investigation revealed that some of the Chinese claims were for businesses related to opium. This eventually led to the creation of Canada’s first anti-drug law.

Shortly after, Japan and Canada reached a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” to reduce Japanese immigration to 400 people a year. In 1928, that number was further reduced to 150.

The Chinese head tax remained at $500, but in 1923, the Chinese Exclusion Act came into effect. Under the act, Chinese immigration to Canada was completely banned. The exclusion act was repealed in 1947, mainly as a result of Canada’s signing the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

100 years later: A surge in anti-Asian sentiments

Since the formative decades of Vancouver’s founding, much has been gained from a human rights perspective. But 2020 ushered in the COVID-19 pandemic, and with it a dramatic rise in anti-Asian violence, fanned by anti-China sentiment.

Vulnerable people, especially lower-income seniors and women, were targeted. Such instances, along with anti-Black, anti-Muslim and anti-Indigenous attitudes, are all part of the legacy of historic and current racism.

Raising awareness of the 1907 anti-Asian riots will hopefully encourage dialogue and reflection on who has the right to live here as we pursue equality and justice for all.

Canada’s local food system faces major roadblocks without urgent policy changes

Canada’s local food system faces major roadblocks without urgent policy changes  Why a ‘rip-off’ degree might be worth the money after all – research study

Why a ‘rip-off’ degree might be worth the money after all – research study  Disaster or digital spectacle? The dangers of using floods to create social media content

Disaster or digital spectacle? The dangers of using floods to create social media content  Why financial hardship is more likely if you’re disabled or sick

Why financial hardship is more likely if you’re disabled or sick  The American mass exodus to Canada amid Trump 2.0 has yet to materialize

The American mass exodus to Canada amid Trump 2.0 has yet to materialize  Stuck in a creativity slump at work? Here are some surprising ways to get your spark back

Stuck in a creativity slump at work? Here are some surprising ways to get your spark back  Columbia Student Mahmoud Khalil Fights Arrest as Deportation Case Moves to New Jersey

Columbia Student Mahmoud Khalil Fights Arrest as Deportation Case Moves to New Jersey  Britain has almost 1 million young people not in work or education – here’s what evidence shows can change that

Britain has almost 1 million young people not in work or education – here’s what evidence shows can change that  Youth are charting new freshwater futures by learning from the water on the water

Youth are charting new freshwater futures by learning from the water on the water  AI is driving down the price of knowledge – universities have to rethink what they offer

AI is driving down the price of knowledge – universities have to rethink what they offer  The Beauty Beneath the Expressway: A Journey from Self to Service

The Beauty Beneath the Expressway: A Journey from Self to Service  How to support someone who is grieving: five research-backed strategies

How to support someone who is grieving: five research-backed strategies  Locked up then locked out: how NZ’s bank rules make life for ex-prisoners even harder

Locked up then locked out: how NZ’s bank rules make life for ex-prisoners even harder  Office design isn’t keeping up with post-COVID work styles - here’s what workers really want

Office design isn’t keeping up with post-COVID work styles - here’s what workers really want  Why have so few atrocities ever been recognised as genocide?

Why have so few atrocities ever been recognised as genocide?