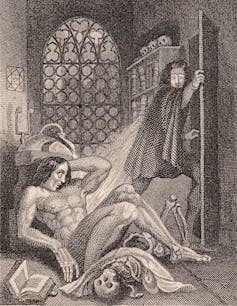

Frankenstein abandons his monstrous creation. Frontispiece to Mary Shelley's 1831 edition of Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein tells the tale of a monster created by an obsessed scientist. Since its inception in 1816, the story has haunted scientists, warning against the worst excesses of scientific misadventure and technological hubris.

However, in an attempt to rescue the profession of science from Shelley’s potent critique, the 21st-century scientific community seems to have rallied around an emerging myth about Frankenstein, that it was inspired by the Tambora volcano in the distant archipelago now known as Indonesia.

Today, Tambora’s eruption has been presented as a lesson about the impact of climate change.

I investigated this Tambora–Frankenstein myth and its roles, goals and meanings as ascribed by various scholars and journalists.

I argue that blaming Tambora for all the bad weather of 1816 in Europe and for European poverty and misery is too far-fetched, let alone to suppose the consequences of the eruption led to the creation of the Frankenstein novel.

Furthermore, a short-term climate-cooling event like Tambora is not a suitable analogy for global warming, which is impacting upon the Earth in a long-term catastrophic manner.

The myth

According to the myth, the dust and ash thrown into the atmosphere by the 1815 eruption of Tambora volcano – located on what is now Sumbawa Island, Indonesia – travelled around the world, dimming the sun in Europe the following year and causing temperatures there to drop, creating storms, producing frosts and floods, and generally darkening the landscape.

This extreme weather supposedly decimated harvests as well, leading to hunger, poverty and displacement.

A 19th-century painting of an East Indies eruption. Raden Saleh

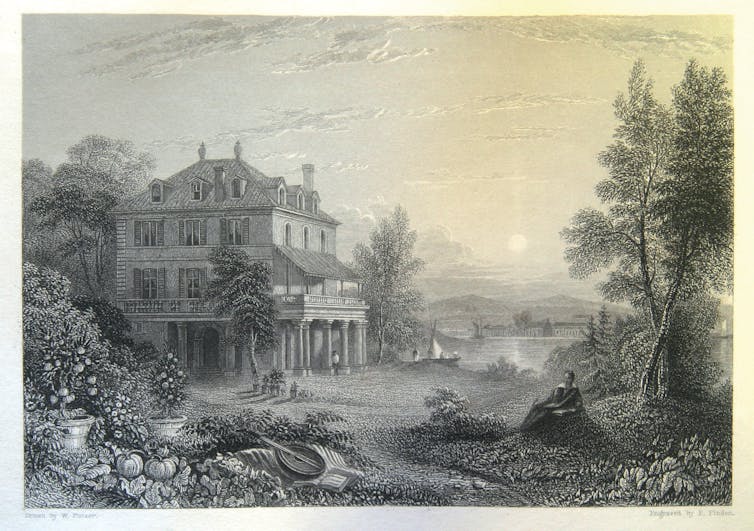

Mary Shelley had the chance to witness this misery firsthand as she travelled across Europe with her soon-to-be-husband, the radical poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. The couple were heading to the Swiss villa of another English poet, Lord Byron.

All three of them were confined indoors by the bad weather, offering Mary Shelley plenty of time to reflect upon what she had seen and to experiment with ways to put it onto paper. As she wrote, she inflected the foreboding landscapes and human misery into her emerging horror novel.

Lord Byron’s Swiss Villa (an engraving by Edward Finden after an 1832 painting by William Purser) British Library

A likelier inspiration

The Tambora–Frankenstein myth regularly re-emerges from the pens of science writers, most notably when a volcano erupts or a new Frankenstein movie is released.

See, for instance, these reports in CNN, The New York Times, New York Post, Forbes, The Paris Review, The Guardian, The Smithsonian Magazine, Slate, The Independent, The Daily Beast, Vice and also here in The Conversation. As the Taal volcano goes through an eruptive event in the Philippines, the myth has also emerged there.

Yet the myth is riddled with problems. To start with, if 1816 was colder and rainier and icier than the years preceding or following, it is not clear the Tambora eruption was the cause.

A report from Switzerland, where Shelley wrote Frankenstein, casts doubt on the scale of Tambora’s impacts and suggests it would have had a minor role, if any, in creating any extra extreme weather or any extra hunger and destitution.

A far more significant contributor to human misery at this time was the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), which had long degraded European trade and decimated farms and towns.

If Shelley was attempting to personify human misery and displacement into the restless character of her monster, the root cause was more likely war rather than a volcanic eruption.

This is not to say Tambora volcano did not inflict human misery. Probably 50,000 or more people died on the islands of Sumbawa, Lombok, Bali and Java, some during the initial 1815 eruption but mostly through subsequent hunger and disease. Another 50,000 people in other parts of the world may also have succumbed to hunger and disease as 1816’s harvests failed under the dimmed sun.

Yet, to get things in perspective, the Napoleonic Wars had killed 5 million people by 1815. Soon after, the Java Wars waged by European empires against local East Indies kingdoms resulted in more than 200,000 deaths.

In the race to cause human misery, wars seem to outpace volcanoes, at least during Mary Shelley’s time.

The last day of the Napoleonic Wars, 1815. The Battle of Waterloo by William Sadler (1839)

The last day of the Java Wars, 1830. Nicolaas Pieneman's 1830 painting

Flashes of inspiration?

The climate change lesson of the Tambora-Frankenstein myth runs as follows. If humans do as Tambora did: emitting vast pollutants into the atmosphere, then we are going to force upon the world myriad 1816-esque horrors: dark skies, floods and storms, agricultural collapse, economic stagnation, plus human misery, poverty and displacement.

However, the Tambora eruption forced only limited temporary climate cooling for about a year in only a few parts of the globe. The climate crisis of global warming, in contrast, is nigh-on permanent. It also directs the thermometer in the opposite direction.

There’s also an obvious dissonance between their respective causes (natural volcanic exhaust versus human-made industrial pollution) such that any mode of response must be completely different. Dealing with an erupting tropical volcano, though of great importance, is not the same as dealing with climate change.

Besides, there are much better ways of foregrounding the dangers of climate change than resorting to an errant volcanic analogy.

Another problem with the Tambora–Frankenstein myth is the way it ignores other inspirations for the Frankenstein novel.

Here again, Napoleon deserves a mention – alongside a mention of the French Revolution. Just as Napoleon took the high ideals of the French Revolution and transformed them into military conquest, so Dr Frankenstein took the high ideals of the Scientific Revolution and turned them into a monstrous project.

Napoleon’s 1815 return to France by Baron von Steuben (1818) Brown University Library

Shelley’s Frankenstein was also partly inspired by the Luddite uprising. English textile workers had rebelled against the introduction of machines that were threatening them with unemployment – and thus impoverishment.

During the years 1811-1816, some Luddites chose to smash the offending machines. In response, the English parliament introduced the death penalty for such acts. Lord Byron, before he moved to Switzerland, criticised this draconian measure in a speech to the British House of Lords.

As well as rebellion and revolution, Mary Shelley’s various experiences with childbirth, motherhood and family are also important in the way she crafted Frankenstein, as were her journeys through Europe, the books she read while staying in Byron’s Swiss villa, and her awareness of the weird science of animal electricity.

Probably, Shelley didn’t need Tambora to create Frankenstein, but she did need all these other inspirations.

The only reason the Tambora–Frankenstein myth has become popular is not that it helps explain the creation of Frankenstein but because it tries to disarm Mary Shelley’s haunting critique of science.

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer  How ongoing deforestation is rooted in colonialism and its management practices

How ongoing deforestation is rooted in colonialism and its management practices  Extreme heat, flooding, wildfires – Colorado’s formerly incarcerated people on the hazards they faced behind bars

Extreme heat, flooding, wildfires – Colorado’s formerly incarcerated people on the hazards they faced behind bars  Fungi are among the planet’s most important organisms — yet they continue to be overlooked in conservation strategies

Fungi are among the planet’s most important organisms — yet they continue to be overlooked in conservation strategies  Parasites are ecological dark matter – and they need protecting

Parasites are ecological dark matter – and they need protecting  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus

How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus  Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research

Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research