Even before the pandemic, the UK fashion retail industry was struggling. John Lewis, M&S and Debenhams had all announced losses, job cuts and store closures, while House of Fraser was taken over. Since lockdown, Oasis and Warehouse have entered administration, and John Lewis has said that not all its stores will reopen.

One of the challenges for these retailers is cut throat price competition from international rivals like Primark and H&M, and online retailers like Pretty Little Thing and Misguided. Low-price garments became all the more attractive to consumers after their spending power was weakened by the financial crisis of 2007-09.

This brought about the era of fast fashion – low quality clothes needing replaced more quickly, and consumers who see them as disposable. The price of these garments doesn’t reflect their true cost. It ignores both the workers who make them and the carbon footprint from more production, more transportation and more landfill.

Rays of hope

At the turn of the year, there was a feeling that sustainability might be moving back up the agenda. A surge of consumer protests, led by Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg, seemed to herald a public desire for change. To raise awareness that fashion is the second-worst polluter after oil, Extinction Rebellion held a funeral during London Fashion Week 2019.

It seemed possible that consumers might be galvanised to shop more sustainably – especially given the extreme weather conditions of 2019, and fears that there are just ten years left to halt the irreversible consequences of climate change.

Then came the pandemic. With many high street shops forced to suspend trading, the whole industry has been in flux. Brands like Primark and Matalan have cancelled or suspended orders in places like Bangladesh, causing some factories to close. There may have been big environmental benefits from the world at a standstill, but it will be little consolation to garment workers who are furloughed or jobless.

Yet amidst all this upheaval, there is an an opportunity for the fashion industry – both to help these workers and more broadly to put sustainability at the heart of their business.

The decisions by fashion retailers like Burberry and Prada to divert into making medical gowns and masks for healthcare workers are a good starting point. If companies can make positive changes to help manage coronavirus, they can also address fast fashion.

If, for example, companies paid garment workers the living wage for their part of the world, they could use it in their marketing to garner a competitive advantage. Paying a living wage doesn’t significantly increase the cost of garments.

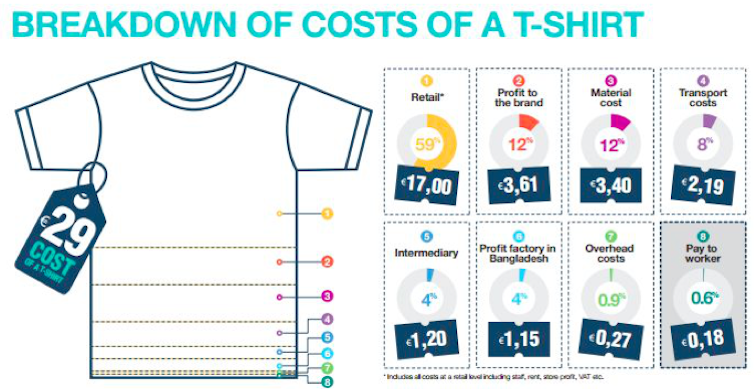

Take the example of a T-shirt with a retail price of £29, for which the worker receives 0.6% or 18p. If that was doubled to 36p, it would not increase the overall price by very much. Paying a living wage should enable workers in developing countries to afford nutritious food, clean water, shelter, clothes, education, healthcare and transport, while leaving some left over.

One fashion entrepreneur that has developed a different way of helping garment workers during the pandemic is Edinburgh-based Cally Russell. He set up the Lost Stock initiative, which sells the garments from orders cancelled by UK fashion retailers by purchasing garments directly from manufacturers in Bangladesh.

A Lost Stock box of clothes costs £39. Almost a third is donated to the Sajida Foundation, which is giving food and hygiene parcels to Bangladeshis struggling during the pandemic. For maximum transparency, Lost Stock also provides a price breakdown that outlines the costs to the manufacturer, the charity and the initiative itself.

Cool to care

Another tactic that fashion marketers could use is to encourage in consumers a similar cool-to-care ethos to that brought out by the pandemic – as seen with the UK’s weekly clapping for key workers, for example. Business in numerous sectors are already focusing their marketing message on supporting NHS workers to capitalise on this spirit of collective solidarity.

Fashion marketers could channel people’s desire for self-gratification towards buying clothes that contribute to the social good. My research illustrates the discomfort consumers experience when aware of allegations of both garment-worker and environmental exploitation, so it should be possible for marketers to benefit from doing the reverse.

TOMS (Tomorrow’s Shoes) is an example of a fashion business with giving at the core of its strategy: for every pair of shoes sold, a pair is donated to a child in need. Since 2006, 100 million pairs of shoes have been donated, and TOMS has since branched into areas like eyewear.

Another example is Snag Tights, which is supporting NHS frontline workers with a free pair of tights for every order placed. The company markets its tights as vegan friendly and free of plastic packaging, and is trying to develop the world’s first fully bio-degradable tights.

Swaps and seconds

One other trend that should definitely be encouraged is initiatives that expand the lifecycle of fashion and textiles. London Fashion Week hosted a fashion swap shop in February for the first time. Similarly, the flagship Selfridges store on London’s Oxford Street began selling second-hand luxury fashion and high-end brands with resale site Vestiaire Collective in 2019.

There has also been a rise in fashion libraries that rent fashion garments and accessories, allowing consumers affordable access to higher quality and luxury items. Fashion retailers could move in this direction, while also supporting customers by hosting workshops for upcycling garments into something new.

In sum, the fashion industry should take advantage of the pandemic pause and the current mood to show constructive leadership to the global economy. It should use its power to help change our relationship with clothing into something more equal and sustainable for the long term.

Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit

Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit  Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains

Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains  Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape

Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape  Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine

Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine  FDA Targets Hims & Hers Over $49 Weight-Loss Pill, Raising Legal and Safety Concerns

FDA Targets Hims & Hers Over $49 Weight-Loss Pill, Raising Legal and Safety Concerns  SpaceX Pushes for Early Stock Index Inclusion Ahead of Potential Record-Breaking IPO

SpaceX Pushes for Early Stock Index Inclusion Ahead of Potential Record-Breaking IPO  SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates

SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates  Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users

Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users  SoftBank Shares Slide After Arm Earnings Miss Fuels Tech Stock Sell-Off

SoftBank Shares Slide After Arm Earnings Miss Fuels Tech Stock Sell-Off  Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Says AI Investment Boom Is Just Beginning as NVDA Shares Surge

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Says AI Investment Boom Is Just Beginning as NVDA Shares Surge  Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised

Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised  Toyota’s Surprise CEO Change Signals Strategic Shift Amid Global Auto Turmoil

Toyota’s Surprise CEO Change Signals Strategic Shift Amid Global Auto Turmoil  Ford and Geely Explore Strategic Manufacturing Partnership in Europe

Ford and Geely Explore Strategic Manufacturing Partnership in Europe  CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences  American Airlines CEO to Meet Pilots Union Amid Storm Response and Financial Concerns

American Airlines CEO to Meet Pilots Union Amid Storm Response and Financial Concerns  Once Upon a Farm Raises Nearly $198 Million in IPO, Valued at Over $724 Million

Once Upon a Farm Raises Nearly $198 Million in IPO, Valued at Over $724 Million