How familiar are you with the Victorian-era newspaper feature known as the Agony Column? You are likely familiar with its methods and central plot lines, even if you don’t know what it is!

Anonymous personal advertisements made up the Agony Column in the mid- to late- 19th century. Authors of these advertisements sometimes coded them using different kinds of numbered ciphers and pseudonyms.

Although the Agony Column no longer exists as it did in the 19th century, our research has documented how private messages on this public forum have had an enduring impact on fiction, entertainment and popular culture.

Power of encryption

Encryption gave authors writing personal messages the ability to share private messages in a public forum. Personal dramas unfolding there day after day meant the Agony Column was widely popular in 19th-century English newspapers.

In 1881, a book was published about these private messages, in which editor Alice Clay wrote:

“Most of the advertisements … show a curious phase of life, interesting to an observer of human existence and human eccentricities. They are veiled in an air of mystery … but at the same time give a clue unmistakable to those for whom they were intended.”

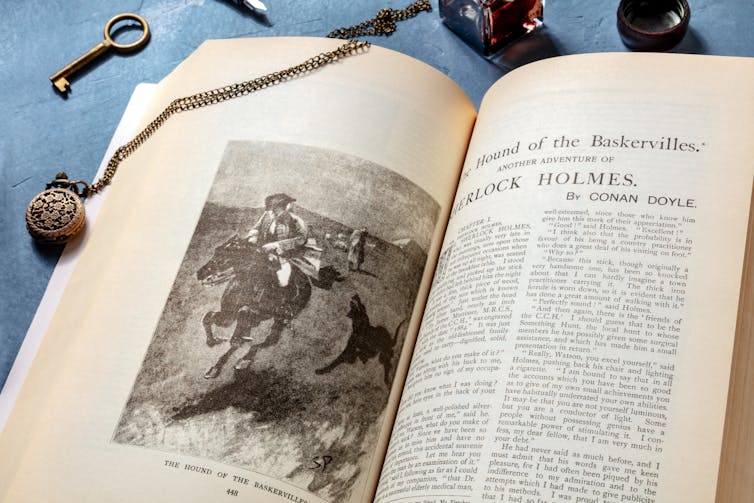

Nearly all original and modern reworkings of Sherlock Holmes contain a plethora of newspaper codes to crack, harkening to the Agony Column. (Shutterstock)

Longing, tragedy and the everyday

Advertisements written by individuals from across the British Empire were dubbed “the agonies” by 1853 because they were full of longing, tragedy and profound misfortune shadowing the Victorian domestic everyday. They occupied prime real estate in the second column on the front page of The Times.

Messages featured voices of desperate parents, forlorn lovers and savvy detectives. Many were published anonymously or under pseudonyms, making it impossible for most readers to know who wrote them.

As interest grew, the private was increasingly made public. Readers not only followed the episodic narratives, but also worked to crack the most puzzling codes and ciphers.

Detectives and amateur enthusiasts alike followed the drama of the agonies. As Stephen Winkworth wrote in Room Two More Guns: the Intriguing History of the Personal Column of the Times, the Agony Column became “more a meeting-place than a market-place and a forum where national quirks and characteristics can be expressed, where lovers can make their rendezvous and lost causes can be proclaimed.”

Fascination shaped novels

During the Victorian era, fascination with the Agony Column shaped both newspapers and novels.

Elements of sensational stories like the Constance Kent Road Hill House murder from front-page news began to appear in novels like Lady Audley’s Secret.

Original and modern reworkings of Sherlock Holmes contain a plethora of newspaper codes to crack. In the 2020 Netflix film adaptation of Enola Holmes, based on Nancy Springer’s novels, Sherlock Holmes’ case-cracking younger sister, Enola, communicates with her missing mother via ciphers.

Netflix video about codes in ‘Enola Holmes.’

Far beyond Sherlock and spinoffs, many popular films have had their plots advanced by the personal columns in the newspaper: movies like Ghost World (2001), Kissing Jessica Stein (2001) and Desperately Seeking Susan (1985).

Comparing novels and ‘the agonies’

We explore this cultural fascination in the exhibition News and Novel Sensations online through the McGill Library.

This includes access to two data sets: Our research team scraped 650,000 sentences from the Agony Column of The Times between 1860 and 1879, and over 25 million words from a corpus of 220 Victorian novels from 1800 to 1920.

Both datasets are available for anyone to explore and download on the project webpage. This will be a valuable resource for those studying the Victorian era and print history.

We will use both computational analysis of those data sets, and close reading, to continue to explore ways newspapers and the Agony Column featured in and shaped Victorian novels and Victorian readers’ experiences.

Victorian detective’s perspective

1874 image from ‘Figaro’s London Sketchbook of Celebrities,’ showing Ignatius Pollaky. (Lindsay Scrapbook/Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

While the agonies and coded advertisements have captured some time in the spotlight thanks to the popularity of film productions of Sherlock and Enola Holmes, understanding just how popular or influential they were on Victorian society is difficult today.

Visitors to the website can explore some of the encrypted stories of The Times in a few unexpected ways, and gain a firsthand glimpse of another era’s print media.

Ignatius Pollaky, the so-called real-life Sherlock Holmes, was known for advertising his own business in the Agony Column and for inserting mysterious notes and messages in the newspaper relating to his cases.

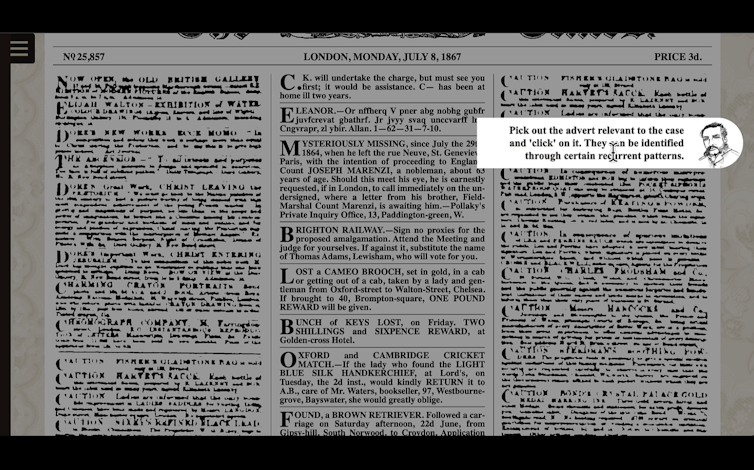

We created a game as part of the exhibit called Pollaky’s Agonizing Adventure. The game allows visitors to track coded clues in the agony columns by following fictionalized detective case notes.

Visitors can experience how the agonies were embedded in the emerging world of detective practice, and experience how the agonies made communicating private messages and plans possible in the public medium of the newspaper.

The front page of ‘The Times’ as the player sees it in an online exhibit game, Pollaky’s Agonizing Adventure, designed to teach tracking coded clues in the Agony Columns. (Jacquelyn Sundberg and Nathalie Cooke)

Changing vocabulary

Do you write like a Victorian? How far has our vocabulary shifted since that time? Our research team created the Victorian Vibecheck to allow visitors to create period-appropriate text.

Vibecheck quantifies how rarely, if ever, words in a given text appear in our corpus of more than 450 Victorian novels. The program then gives you a score based on whether it over- or under-uses words.

Visitors can enter their own text or choose from a list of examples to see if they can approximate a Victorian vibe.

How closely do Victorian novels resemble the agonies, or does our own language resemble the Victorians’? We invite visitors to explore for themselves.

Google and NBCUniversal Strike Multi-Year Deal to Keep NBC Shows on YouTube TV

Google and NBCUniversal Strike Multi-Year Deal to Keep NBC Shows on YouTube TV  Squid Game Finale Boosts Netflix Earnings, But Guidance Disappoints Investors

Squid Game Finale Boosts Netflix Earnings, But Guidance Disappoints Investors  FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Face Senate Oversight After Controversy Over Jimmy Kimmel Show

FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Face Senate Oversight After Controversy Over Jimmy Kimmel Show  Mexico Probes Miss Universe President Raul Rocha Over Alleged Criminal Links

Mexico Probes Miss Universe President Raul Rocha Over Alleged Criminal Links  Netflix’s Bid for Warner Bros Discovery Aims to Cut Streaming Costs and Reshape the Industry

Netflix’s Bid for Warner Bros Discovery Aims to Cut Streaming Costs and Reshape the Industry  FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Testify Before Senate Commerce Committee Amid Disney-ABC Controversy

FCC Chair Brendan Carr to Testify Before Senate Commerce Committee Amid Disney-ABC Controversy  Disney’s ABC Pulls Jimmy Kimmel Live! After Controversial Remarks on Charlie Kirk Killing

Disney’s ABC Pulls Jimmy Kimmel Live! After Controversial Remarks on Charlie Kirk Killing  Pulp are back and more wistfully Britpop than before

Pulp are back and more wistfully Britpop than before  Trump-Inspired Cantonese Opera Brings Laughter and Political Satire to Hong Kong

Trump-Inspired Cantonese Opera Brings Laughter and Political Satire to Hong Kong  Some ‘Star Wars’ stories have already become reality

Some ‘Star Wars’ stories have already become reality  Disney Investors Demand Records Over Jimmy Kimmel Suspension Controversy

Disney Investors Demand Records Over Jimmy Kimmel Suspension Controversy  Jazz Ensemble Cancels Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Shows After Trump Renaming Sparks Backlash

Jazz Ensemble Cancels Kennedy Center New Year’s Eve Shows After Trump Renaming Sparks Backlash  Paramount Skydance Eyes Streamlined Merger with Warner Bros Discovery Amid $60 Billion Offer Rejection

Paramount Skydance Eyes Streamlined Merger with Warner Bros Discovery Amid $60 Billion Offer Rejection  Trump to Pardon Reality Stars Todd and Julie Chrisley After Tax Fraud Conviction

Trump to Pardon Reality Stars Todd and Julie Chrisley After Tax Fraud Conviction