Nowadays, we probably never stop to think about why money was invented. If you are a cynical person, you won’t be surprised to learn the prime motivation was to make a profit for rulers.

About 2,600 years ago, the kings of Lydia in modern-day Turkey hit upon a clever scheme. They turned the silver and gold everyone had been using to buy and sell things into coins with their emblem on it, and forced everyone living in their territory to use it. But the face value of the coin was greater than the value of the metal content. The difference went into their tunics, and everyone has been doing it ever since.

A Lydian coin featuring a lion and a bull, circa 561-546 BCE. Classical Numismatic Group/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Even the Lydians would have been surprised by the phenomenal success of $TRUMP, the recently launched cryptocurrency modestly bearing the name of the new President of America and now worth billions.

But Trump’s coin is nothing new. In a pre-social media world, coins were the ultimate propaganda tool. Rulers used them to advertise themselves and their achievements and any messaging they wanted to get across.

Alexander the Great, the god

Alexander the Great was the first person to put his own image on Greek coins, hitherto the preserve of the gods. But he came to consider himself a god which gave him the OK.

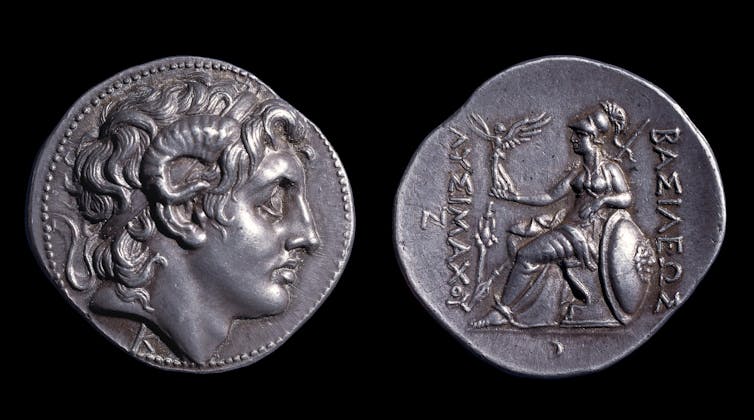

His vast coinage became the standard issue for his successors. The obverse shows the head of Alexander wearing a ram’s horn, indicating the Horns of Ammon – the iconography thanks to an Egyptian Oracle which identified him as being the son of the god Zeus Ammon.

The head of Alexander, and the goddess Athena holding Victory in her hand, circa 305 BCE-281 BCE. © The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

The reverse has the goddess Athena personified as Nikephoros (bringer of victory) holding Victory in her hand with a spear and shield, and the inscription naming King Alexander. You definitely wanted Athena on your side.

Coins were primarily minted to pay the army. There were no fancy economic notions of maintaining an adequate money supply; that was simply a by-product. But coins were the main medium in which everyone got to see Alexander as a divine being with the warrior goddess par excellence on his side.

Roman battles

The Romans were the best at using coins for propaganda.

This coin of Julius Caesar features, on the obverse, Caesar at the height of his power with a legend naming him as “Dictator in Perpetuity”, an honour bestowed on him by the Roman Senate in mid-February 44 BCE.

This coin of Julius Caesar at the height of his power names him ‘Dictator in Perpetuity’, circa 44 BCE. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

On the reverse is his mythical ancestor Venus holding Victory. Essentially, he was making himself king and ending the Roman Republic. If you know your Roman history, or Shakespeare, you will realise this was not going to go down well.

And indeed, it did not. Caesar was assassinated just one month later on the Ides of March.

Marcus Junius Brutus celebrated the event with one of the most famous coins in history bearing his own bust and name on the obverse.

On the reverse, above the inscription, the “pileus” cap was a symbol of freedom often worn by recently freed slaves. The daggers on either side were, of course, the weapons used to slay Caesar.

This coin commemorates the Ides of March. Münzkabinett Berlin

Jerusalem the Holy

The First Jewish Revolt started in 66 CE, when the Jews tried to reclaim their freedom from the Romans and reconquered Jerusalem. They issued coins proclaiming their independence from Rome.

The obverse features a chalice with an inscription in paleo-Hebrew alphabet reading (from right to left): “Shekel Israel Year 3”, and the reverse with three budding pomegranates and an inscription: “Jerusalem the Holy”.

Other coins in the series had the legend “The freedom of Zion”, which can be interpreted as a political statement to rally support and to emphasise Jerusalem as the capital.

Shekel from the first Jewish Roman war, circa 66-70 CE. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The Romans did not take kindly to being beaten up. Their Emperor Vespasian subdued the revived Jewish state and destroyed the Temple, issuing umpteen versions of the famous “Judaea Capta” coins.

Struck in 71 CE, this coin has Vespasian on the obverse. On the reverse, on the right side is a female personification of the Jewish nation in mourning, seated beneath a palm tree; on the left side, a captive Jew with his hands tied behind back and captured weapons behind.

This Roman coin features Vespasian, a female personification of the Jewish nation in mourning, and a captive Jew. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The circulation of these coins in the province of Judaea (Israel) for the next 25 years would have rubbed it in for the local population.

When the Jews revolted again in 132–135 CE, they once more issued their own coinage. They gathered in all the coins circulating and overstruck them with their inscriptions, first expressing hope for rebuilding the temple and then, in desperation as the revolt failed, “For the freedom of Jerusalem”.

Coins in the modern world

The tradition of using coins for propaganda and profit has continued throughout history. Even in modern times, we are used to seeing the head of the monarch on our coins.

Coins and banknotes are still fiduciary, which means that they have little or no intrinsic value. Their value derives from the state enforcing their use and guaranteeing them, just as it was for the Lydians.

And even Trump’s meme coin is not his only venture into coins.

Private mints can issue commemorative coins which are not actually legal tender. Trump’s version are “medallions” proudly “minted in America” of 99.9% pure gold or silver, with prices starting from US$100.

Sadly for Trump, the “Presidential Gold Aurum® Note”, a “24k gold bill made with the most technologically advanced process in the world” is not doing quite so well, retailing on his own site for a mere US$34.99.

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?