In recent months, Vladimir Putin and his proxies have been foreshadowing a change in Russia’s nuclear doctrine. This is the set of rules that spells out when and how his country might resort to the use of its nuclear arsenal, which is currently the largest in the world. Most recently his deputy foreign minister, Sergei Ryabkov, said the revisions to the rulebook were “connected with the escalation course of our western adversaries”. In other words: it’s not us, it’s you.

You don’t have to read too much between the lines to discern a connection between the growing clamour by some in the west to allow Ukraine to use western long-range missiles against targets deep inside Russia and Russia’s decision to reconsider under what circumstances it would use its nuclear arsenal.

Over the past couple of years – since shortly after he initiated Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine – Putin and his inner circle have regularly invoked Russia’s nuclear deterrent, writes Christoph Bluth, an expert in nuclear proliferation and international security at the University of Bradford. All it seems to take is for the west to agree another large package of funding, or change the terms of its aid to Kyiv for the Kremlin to dust off the doomsday scenario.

So it comes as little surprise that, shortly after Volodymr Zelensky gave his impassioned speech to the United Nations general assembly yesterday restating his country’s urgent need for more support and more latitude in how to use it, Putin announced his country’s new “draft” nuclear doctrine. Henceforth, he said, Russia would consider using nuclear weapons if it was attacked by any state with conventional weapons. The trigger for the launch of nuclear missiles against Ukraine or any of its allies, he said, would be “reliable information about a massive launch of aerospace attack means and their crossing of our state border”.

Bluth recounts how, earlier this month, one of Putin’s proxies, Alexander Mikhailov, the director of the Bureau of Military Political Analysis, recently called for Russia to “bomb plywood mock-ups of London and Washington to simulate a nuclear attack, so that it would ‘burn so beautifully that it will horrify the world’.” Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of Russia’s lower house, said that any attacks against Russia would prompt it to respond with nuclear weapons. He is reported to have added – with what appears to have been ghastly relish – that the European parliament in Strasbourg was “only a three-minute flight for a Russian nuclear missile”.

It’s tempting to dismiss Russia’s threats as just so much sabre-rattling. And there have been plenty of voices in the west urging leaders to defy Putin’s threats. After Ukraine launched its lightning raid into Russia’s Kursk province in August, Zelensky said it was clear that Russia’s red lines were a bluff. He said: “The naive, illusory concept of so-called red lines regarding Russia, which dominated the assessment of the war by some partners, has crumbled apart these days.”

Colin Alexander, a specialist in political commnunications at Nottingham Trent University, believes that since the end of the cold war the focus of what he calls “fear propaganda” has changed. It has moved away from the prospect of nuclear annihilation to “other threats, such as extremism, pandemics and migration”.

But anyone who grew up during the cold war will remember the omnipresent fear of the “three-minute warning” regularly reinforced by government messaging, TV documentaries and dramas. These all served to remind everyone that a nuclear holocaust was only a series of wrongheaded decisions away. It’s that atmosphere of peril, writes Alexander, which makes a leader’s threats believable.

And the “madman theory” which holds that only an unstable leader would contemplate pushing the button, has helped lull people into the idea that a nuclear conflict is indeed unthinkable, because surely no leader would be mad enough. But Alexander concludes by citing the one leader who actually did drop a nuclear bomb in an enemy:

US president Harry S. Truman pushed the button in 1945. He was then given detailed reports of the death and destruction that his decision caused to Hiroshima. Then he pushed the button again to annihilate Nagasaki.

Zelensky’s plea

Zelensky’s speech to the UN general assembly was compelling and moving in equal measure. He warned of intelligence reports that Russia was preparing to target Ukraine’s nuclear power plants as part of its campaign to wreck the country’s energy infrastructure before winter. He mourned for the children of Ukraine, who “are learning to distinguish the sounds of different types of artillery and drones because of Russia’s war”. And he restated his ten-point plan for peace, which involves Russia withdrawing from all the lands it has occupied since 2014.

But, Stefan Wolff notes, a growing number of countries are lining up behind a peace plan proposed earlier in the year by China and Brazil, which would freeze the conflict along the existing frontlines before proceeding to negotiations.

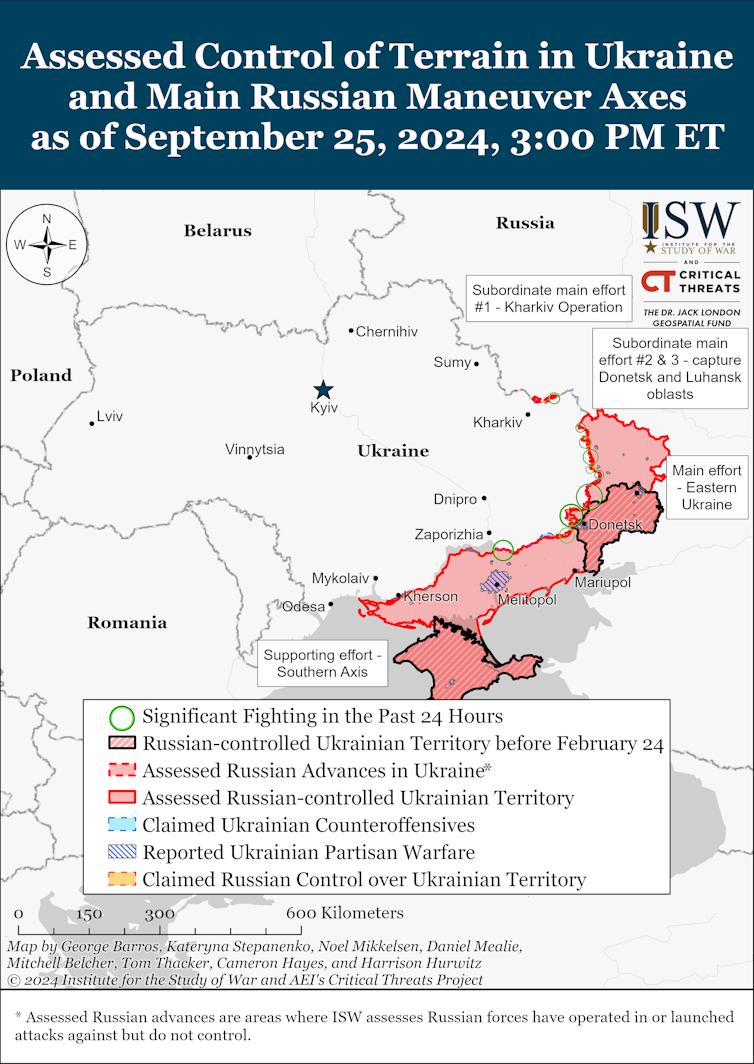

The state of the conflict in Ukraine as at September 25. Institute for the Study of War

Wolff, an expert in international security at the University of Birmingham, believes this plan is deeply flawed. For one thing it would inevitably involve Kyiv being forced to give up territory illegally annexed by Russia. It would also give Russia time to regroup, rearm and train extra troops and would almost certainly not guarantee a lasting peace, but would simply stave off another Russian assault on Ukraine.

But Zelensky faces two key problems which make his diplomatic mission that much harder. His voice is in danger of being drowned out by the conflict in the Middle East, which appears almost inevitably bound for a ground war in Lebanon in days to come. And the prospect of Donald Trump winning a second term in about six weeks’ time, means that the days of Washington as Kyiv’s staunchest partner could well be coming to an end.

As the conflict drags on – 31 months and counting – there is evidence that some Ukrainians would give up territory in return for peace and an end to the killing. Our team of political scientists, Kristin M. Bakke of UCL, Gerard Toal of Virginia Tech and John O’Loughlin of University of Colorado Boulder, have been polling Ukrainians since the invasion and have detected a definite shift in attitudes towards the conflict.

While most Ukrainians still hate the idea of having to give up territory to Russia, support for the proposition that Ukraine should “continue opposing Russian aggression until all Ukrainian territory, including Crimea, is liberated” had fallen from 71% in 2022 to 51% now. And, while in 2022 just 11% of respondents agreed with “trying to reach an immediate ceasefire by both sides with conditions and starting intensive negotiations”, that number had almost tripled in the most recent polling.

Interestingly, the researchers note, while most people they spoke with professed unchanged support for their country’s war effort, a growing number said they were worried that their fellow Ukrainians were beginning to suffer from war-weariness.

Land grabs

Russia is already calling for more territory in eastern Ukraine in the form of a “buffer zone” around Ukraine’s second city, Kharkiv in the north-east of the country. This, the Kremlin claims, is to protect Russian towns from shelling and missile attacks from Ukrainian territory.

Interestingly, writes Iain Farquharson, a security expert and military historian at Brunel University London, Israel has also proposed setting up a buffer zone in southern Lebanon, to protect Israelis living near the the country’s northern border from Hezbollah missile barrages.

Farquharson considers the history of buffer zones in the Middle East and beyond. Firstly, buffer zones rarely live up to their supposed function – as Afghanistan’s misfortune to be between British India and southern Russia in the 19th century and Lebanon’s bad luck to be between Syria and Israel in the 1960s and 1970s amply demonstrate.

But what Russia and Israel are proposing are not so much buffer zones as land grabs, pure and simple. There’s no sense that either country is willing to contribute any of its own territory to these so-called demilitarised areas (or that they’ll actually be demilitarised). They should, he writes, “instead primarily be seen as a way of formalising control over contested territory to protect their home bases, which would give them a military advantage”.

After the Iran war, Persian Gulf nations face tough decisions on the US – a former diplomat explains

After the Iran war, Persian Gulf nations face tough decisions on the US – a former diplomat explains