It would be a brave – or foolhardy – analyst who presumes to predict the outcomes of the talks which continue in Doha. But the fate of Gaza and its 2 million inhabitants as well as the 109 remaining Israeli hostages being held in Gaza, will depend on a political solution being found. And there are many moving parts involved, not all of them in the Middle East.

Despite the US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, talking up what he referred to as a “bridging proposal”, designed to overcome the differences between Hamas and Israel over matters such as whether – and where – the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) would retain troops on the Gaza Strip.

The Netanyahu government wants to maintain a military presence along the Philadelphi corridor, which runs along the southern border that divides Gaza from Egypt. It also wants the IDF to continue to patrol the Netzarim axis, which has been established during the IDF ground operation against Hamas in Gaza and effectively cuts the enclave in two below Gaza City.

The US president Joe Biden spoke with the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, on August 21, and “stressed the urgency” of reaching a ceasefire deal. With his vice-president, Kamala Harris – who has now been formally confirmed as the Democratic Party’s nominee in November’s presidential election – sitting in, Biden is reported to have stated the importance of removing “any remaining obstacles” blocking an agreement with Hamas.

Whether the “remaining obstacles” include Netanyahu’s insistence on retaining an Israeli military presence on the strip is not yet clear. But the previous day an unnamed “administration official” quoted by the BBC said that Netanyahu’s “maximalist statements” were “not constructive to getting a ceasefire deal across the finish line”.

There will be another round of talks in Qatar at the weekend, including representatives from the US and Israel as well as Egyptian and Qatari mediators. Hamas does not have representatives directly engaged in the talks. The group recently lost its chief negotiator when Ismail Haniyeh was killed in Tehran in an assassination widely believed to have been organised by Israeli intelligence. Haniyeh’s successor as Hamas’ political leader, Yahya Sinwar, is believed to be hiding out in Gaza.

Blinken has been shuttling to and from the US, where he attended the Democratic National Convention this week. He will no doubt have conveyed his impressions to Biden as well as to Harris, who will inherit the issue from Biden if she wins the November 5 election. If Donald Trump wins the election, by contrast, things could be very different.

Netanyahu visited Trump’s Mar-a-Lago headquarters at the end of July and was reported to have told the Israeli prime minister to “get your victory and get it over with”. More recent reports that Trump had urged Netanyahu not to agree a ceasefire deal during the election campaign have been denied by both Israel and the Trump campaign.

Amid all this confusion, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: this conflict is likely to play a prominent part in the election campaign, which is now heating up considerably as the Democratic National Convention (DNC) reaches its culmination with Harris’s keynote speech tonight, August 22.

While the DNC has been a slickly presented love-in for the Democrats inside Chicago’s United Center, out on the street, thousands of pro-Palestinian protesters have been making their presence felt, with dozens of arrests after they clashed with police and burned US flags on Tuesday night.

Scott Lucas, a specialist in Middle East politics at University College Dublin, has recently returned from the US and was able to take the political temperature over the conflict. He believes that while Biden – known by protesters as “Genocide Joe” – has a longstanding record as a supporter of Israel, Harris’s position is more nuanced.

This might actually help her in November’s polling, writes Lucas. In a state such as Michigan, seen as crucial to the Democratic Party’s hopes of winning the White House, Biden was trailing Trump by several percentage points. Then he stepped down on July 21 and things changed immediately. Lucas notes:

Within days, a deficit of between three and seven percentage points in polling in Michigan turned into an advantage of between three and four points. This turnaround has shown no signs of reversing itself.

Harris’s public face when it comes to the Israel-Palestine question is certainly more balanced than Biden’s. When Netanyahu addressed a joint session of the US Congress, days after Biden stepped out of the campaign, Harris had conveniently arranged to be elsewhere. Her pronouncements have given equal weight to the welfare of the people of Gaza with the need to rescue the hostages, while also stressing that a ceasefire must be accompanied by progress towards a two-state solution which recognises the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination.

That said, a Democrat group, Muslim Women for Harris-Walz, has announced it has withdrawn its support for the ticket after a request was denied for an American-Palestinian to address the DNC but the family of an Israeli hostage was allowed to speak.

Be that as it may, though, Lucas observes that there’s no real sense that Harris’s chances of victory in November will hang on her opinion on the conflict in Gaza. He identifies what he calls “three realities” on the possibility of a ceasefire.

“Netanyahu – facing an early election and a possible trial on bribery charges if the war ends – cannot afford one. Harris can win whether or not one is agreed. And Gaza’s civilians will continue to die without one.”

Rules of war

Meanwhile the fighting continues and the Palestinian death toll is reported by the Gaza health ministry to have topped 40,000, with the vast majority of casualties civilians.

It seems that every few days the evening news bulletins bring accounts of yet another attack on what the IDF calls a “Hamas target” and what Palestinians say was a school or hospital in which civilians are sheltering. On August 10, an airstrike hit a compound in Gaza city containing a school and a mosque. Palestinian authorities claimed more than 80 people had been killed. The IDF countered by saying it had killed just 19 people, all Hamas fighters, including Hamas commanders.

Just two days later marked the 75th anniversary of the signing of the Geneva conventions in 1949, which spelled out the rules for treatment of civilians in war. Under the rules, schools and hospitals are clearly protected, writes Lawrence Hill-Cawthorne, professor of public international law at the University of Bristol.

But it’s not as simple as that, he cautions. Any building – including those protected under the Geneva onventions – that are being used for military purposes can potentially become a lawful military objective – something that Israel regularly alleges when such buildings are targeted. Hill-Cawthorne explains how the rules work here.

A Palestinian state?

Meanwhile the vexed issue of international recognition of Palestinian statehood remains unresolved. The vast majority of UN members, some 148 countries out of 193, have formally recognised Palestine as a legitimate and sovereign state. But significantly, write Donald Rothwell and Sarah Krause, experts in international law at Australian National University in Canberra, the list does not include the US, UK, New Zealand, Japan, France, Germany, Canada or Australia.

Australia’s Labor government promised recognition would be a priority for its first term. But an attempt by the Australian Greens in May to raise a motion in parliament failed. Rothwell and Krause walk us through what statehood means and whether Palestine fits the bill.

Academic jewel of the Mediterranean

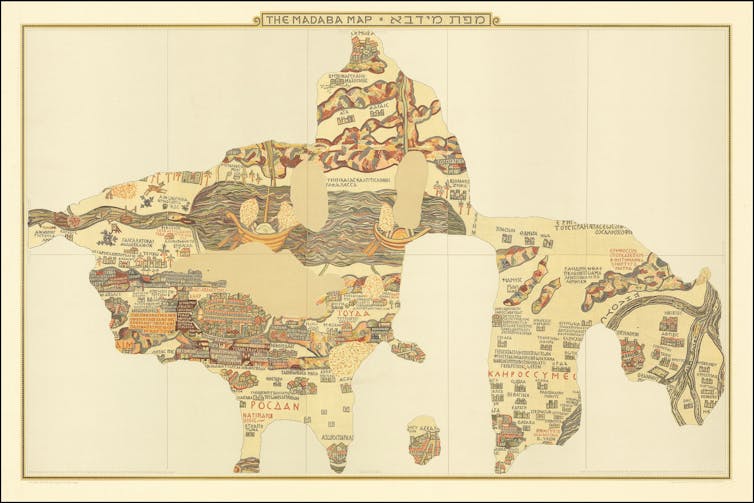

The ‘Medaba Map’ (6th century CE) is part of a floor mosaic in the church of Saint George in Madaba, Jordan, containing the oldest surviving cartographic depiction of Jerusalem. Wikimedia/Paul Palmer

Finally, the land laid claim to by both Israelis and Palestinians has a complex and contested history. But there is considerable evidence that Gaza was once considered a major seat of learning in the Mediterranean of the late Roman empire.

In the 5th and 6th centuries AD, Alexandria (in Egypt), Constantinople (Istanbul), Antioch (Antakya) and Gaza formed a network of prestigious schools at which aspiring young clerics gained an elite education based on Greek classical texts.

Christopher Mallan, a classicist based at the University of Western Australia, believes that education at one of these schools was de rigeur for anyone from the eastern empire hoping to make their way in the civil service.

Mallan gives us the stories of some of the prominent Gazan intellectuals whose work survived them down the ages.

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?