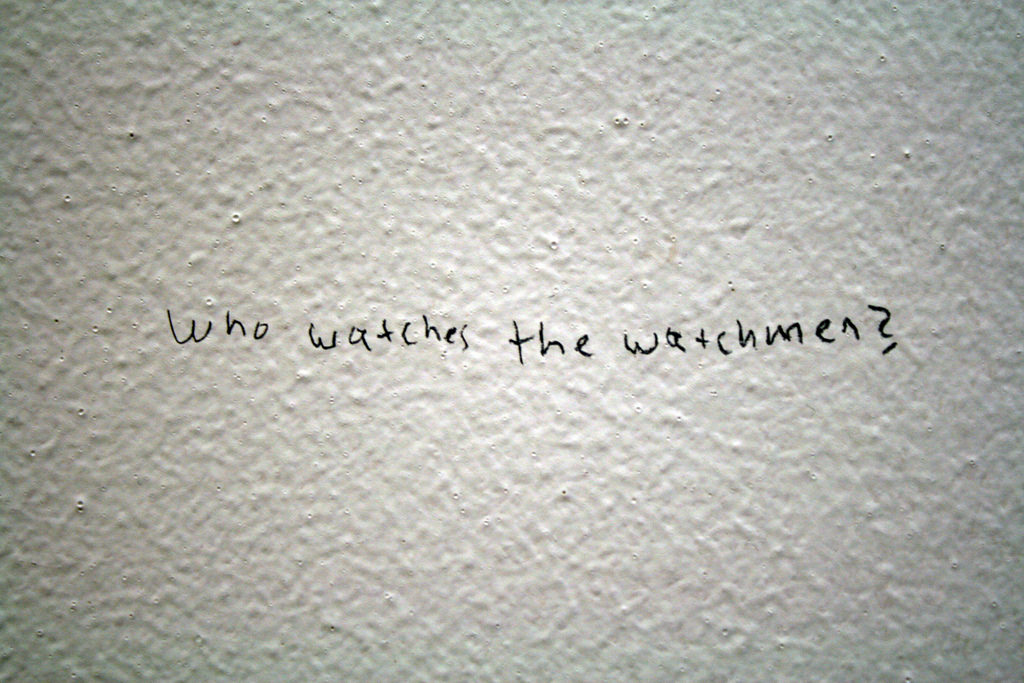

Successive British governments have passed or tried to pass laws granting wide data sharing and surveillance powers, only for them to founder in the European courts due to conflicts with European directives and laws such as the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The EU’s Court of Justice (ECJ) recently heard such a case, brought by Conservative MP David Davis and Labour deputy Leader Tom Watson, which challenges electronic surveillance legislation rushed through parliament in 2014. The court’s judgment, when it comes, will affect UK law. But it will also complicate Britain’s future relations with the EU – particularly if in the meantime the British public votes for Brexit. Would the UK have less guarantees of privacy, protection of personal data and checks on government surveillance were it to vote to leave the European Union?

European Union legislation in this field is made up of a variety of instruments. The just-introduced General Data Protection Regulation governs most collection and exchange of personal data within the EU, while a parallel directive governs how personal data can be collected by and exchanged between police services. There are also several key rulings by the ECJ that have provided important case law decisions regarding the rights to privacy and data protection.

First is the case brought by Digital Rights Ireland to challenge another European law, the wide-ranging data retention directive. This law required companies who provide telephone and internet services to keep basic information on all their customers' internet or phone use just in case the police might want to look at it. The court ruled that while the law’s objective of fighting serious crime and terrorism was legitimate, it went too far in requiring what amounted to mass surveillance without sufficient safeguards. The court ruled the data retention directive invalid.

Second is the case brought by Austrian activist Max Schrems over the data-harvesting activities of tech giants such as Facebook. Under the EU-US Safe Harbour agreement drawn up by the European Commission, the US was assumed to have “adequate” data protection policies in place for companies such as Facebook based in the US. But, following the Snowden files and revelations of mass surveillance by US agencies, the court ruled that this could no longer be supported.

The Davis and Watson case

The case brought by Davis and Watson challenges the Data Regulation and Investigatory Powers Act 2014 (DRIPA) which the UK government passed in response to the EU court striking down the Data Retention Directive. As DRIPA reinstates the very same customer data retention obligations on ISPs and telecoms companies that the court had found unjustifiable in European law, the case has reached the European courts because the legal team argue that while the European law has been struck down, member state versions of it such as DRIPA breach the same rights to privacy and data protection.

Brexit, Britain and privacy

There will be a non-binding opinion from an EU court official on the case in July followed by the final judgment in the autumn, so we won’t know the outcome of this case before the referendum on June 23.

Nevertheless, the ruling will be relevant even if the British public vote to leave the EU. The Schrems case has reinforced that even non-EU countries' data protection laws must be “essentially equivalent” to European law before simplified transfers of personal data between the countries are allowed. This affects both digital businesses and the transfer of policing and security data. While the EU and US recently agreed on a Safe Harbour replacement known as Privacy Shield, this too will likely face a legal challenge as soon as it’s adopted. In fact, the transfer of police data between the EU and Canada is already being challenged.

If Britain leaves the EU it will find it must still comply with European Union laws governing personal data handling and privacy anyway, and any British laws or treaties with the EU that don’t will inevitably be challenged. Conflicts between British and European law will not be easily solved, because EU court rulings are based on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights which takes precedence over ordinary laws and treaties even with non-EU countries – and is much harder to amend.

The upshot is that if the Britain chooses Brexit, the ruling in the Davis and Watson case will effectively establish a non-negotiable demand by the EU regarding data protection and privacy leaving the UK government with an unavoidable choice: either apply EU restraints on mass surveillance of UK citizens, and so lose the British sovereignty that Brexit supporters are campaigning for. Or abandon the framework that allows the simplified transfer of data between police services and digital industries between an independent UK and the rest of the European Union – with the economic and security pitfalls that would bring.

Steve Peers has worked as an independent consultant giving advice during the preparation of impact assessments of EU law in this area..

Steve Peers has worked as an independent consultant giving advice during the preparation of impact assessments of EU law in this area..

Steve Peers, Professor of Law, University of Essex

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday  Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive

Citigroup Faces Lawsuit Over Alleged Sexual Harassment by Top Wealth Executive  Supreme Court Signals Doubts Over Trump’s Bid to Fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook

Supreme Court Signals Doubts Over Trump’s Bid to Fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook  Newly Released DOJ Epstein Files Expose High-Profile Connections Across Politics and Business

Newly Released DOJ Epstein Files Expose High-Profile Connections Across Politics and Business  Google Halts UK YouTube TV Measurement Service After Legal Action

Google Halts UK YouTube TV Measurement Service After Legal Action  CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences  New York Judge Orders Redrawing of GOP-Held Congressional District

New York Judge Orders Redrawing of GOP-Held Congressional District  Federal Reserve Faces Subpoena Delay Amid Investigation Into Chair Jerome Powell

Federal Reserve Faces Subpoena Delay Amid Investigation Into Chair Jerome Powell  Federal Judge Rules Trump Administration Unlawfully Halted EV Charger Funding

Federal Judge Rules Trump Administration Unlawfully Halted EV Charger Funding  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Supreme Court Signals Skepticism Toward Hawaii Handgun Carry Law

Supreme Court Signals Skepticism Toward Hawaii Handgun Carry Law  U.S. Condemns South Africa’s Expulsion of Israeli Diplomat Amid Rising Diplomatic Tensions

U.S. Condemns South Africa’s Expulsion of Israeli Diplomat Amid Rising Diplomatic Tensions