Australia’s unprecedented bushfires have cemented its rural firefighters at the heart of the nation’s identity.

It’s not just that these men and women put themselves in the line of fire. It’s that these “firies” are almost all volunteers, battling blazes for sheer love of their local community.

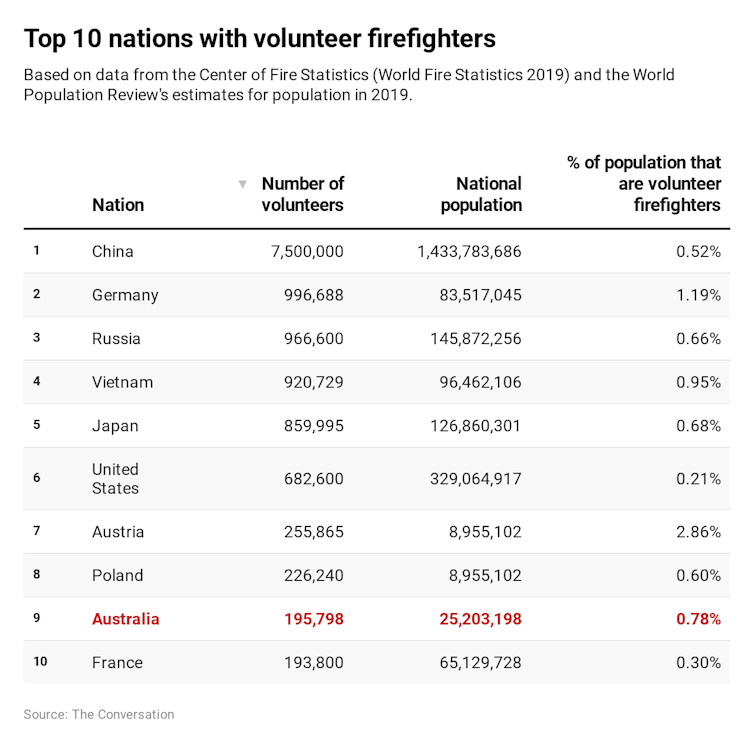

Relying on volunteers isn’t unique to Australia’s rural firefighting brigades. Other countries with large numbers of volunteer firefighters include Austria, Germany, France, the United States, Japan and China.

But Australia arguably relies on these volunteers to an extent unparalleled in the world, due to the country’s sheer size and the extent to which it is prone to bushfire. In terms of sheer scale of fires, only the vastness of Russia and Canada can compete, and neither has a climate and ecology quite so primed to burn.

Almost 1% of the population volunteers

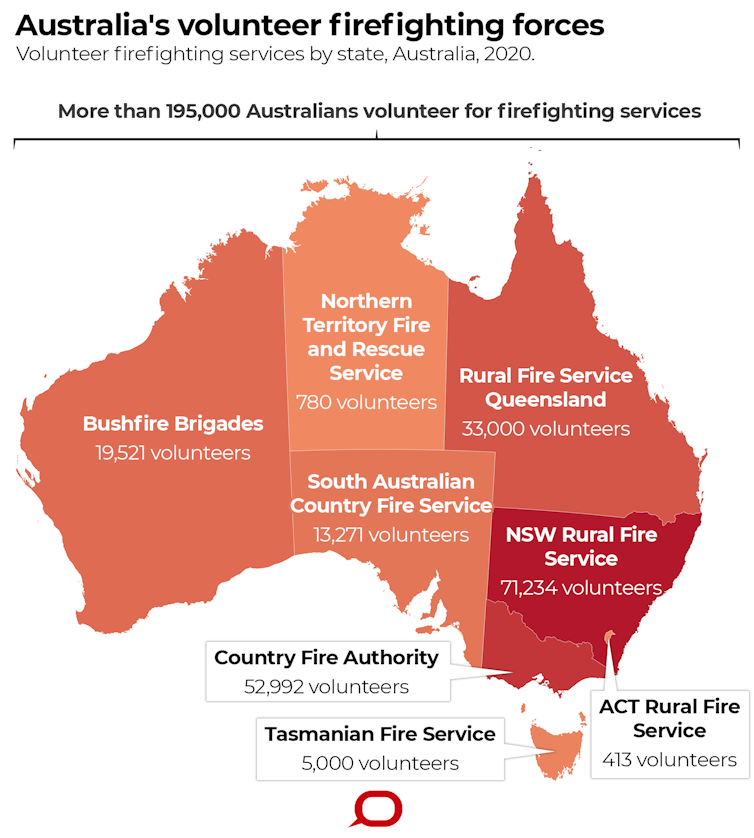

About 195,000 Australians volunteer with the nation’s six state and two territory bushfire services. The most populous state, New South Wales, has the largest number (71,234). The Australian Capital Territory has the fewest (a little more than 400).

The numbers reflect how many people live in rural areas and the degree to which those communities face bushfire risk. Thus Tasmania has 5,000 volunteer fighters despite having a smaller population than the ACT, because relatively more live in small towns.

On raw figures, Australia has the ninth-largest number of volunteer firefighters by nation, after China, Russia, the United States, Japan, Vietnam, Germany, Poland and Austria.

The Conversation

Comparing raw national figures doesn’t necessarily capture the special place of rural firies in Australia. Austria and its neighbours, for example, have cultures of volunteer municipal firefighting brigades that go back nearly a thousand years and cover structural fires as well.

Australia’s voluntary fire brigades are focused on bushfires. If we were to exclude the 71% of the Australia population that live in major cities, the proportion of Australia’s rural population volunteering with a bushfire service is more like 4.5%. This indicates how central these brigades are to local communities.

It hard to put a precise number on the value volunteer firefighters make to Australia’s economy, but it is significant. The amount and quality of volunteer work is, of course, variable. But let’s assume each volunteer gives 150 hours of their time a year. This is likely conservative, given estimates of the time volunteers have given up this season. At the average weekly Australian wage (including superannuation guarantee), the volunteers contribute about A$1.3 billion to the community.

Operations and funding

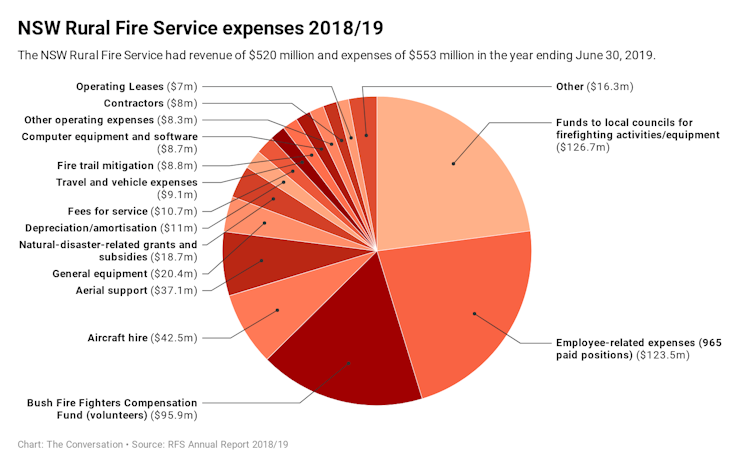

Even though most firefighters in the rural fire services are volunteers, there are still significant costs. The NSW Rural Fire Service, for example, maintains more than 2,000 brigades with their own stations, vehicles and other running costs. It also employs 965 paid staff in administrative and operational roles. Capital investment of $42 million for stations and equipment was made in 2018-19 in addition to running costs.

The following breakdown is indicative of the running costs facing every state or territory service.

Michelle Cull/The Conversation, CC BY

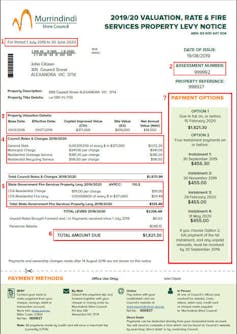

While funding depends on the individual state or territory, in general the services are funded by levies, imposed through state and territory laws.

Sample of a rates notice including the fire services levy for Murrindindi Shire Council, Victoria. Murrindindi Shire Council

Victoria’s Country Fire Authority, for example, is funded under the Country Fire Authority Act (1958) through a property levy. It is collected by local councils and passed on to the state government, which then distributes it to the authority. The levy includes a fixed component plus a variable rate based on a property’s market value.

New South Wales also has a levy tied to council rates (under the Rural Fires Act 1997). But most funding comes from a levy on insurance payments (imposed under the Emergency Services Levy Act 2017). In the 2018/19 financial year these levies raised about $440 million combined. State and federal governments kicked in a further $50 million, with $26 million in “other income” – mostly recouped costs from interstate and overseas deployments and use of its aircraft by other agencies.

The role of donations

Donations have not historically been a major funding source for any state or territory fire service. But in times of crisis the public often want to do their bit by giving money.

In the 2017-2018 financial year, for example, the NSW Rural Fire Service & Brigades Donations Fund received $768,044 in donations. Now it has $50 million or so coming its way due to comedian Celeste Barber’s bushfire appeal.

It’s possible many of those giving to Barber’s fundraiser didn’t realise their money would only go to New South Wales brigades. It’s also possible many thought they might help volunteers directly, such as through reimbursements for taking leave without pay. Others want to ensure volunteers don’t have to buy their own equipment.

Volunteers won’t necessarily benefit directly in the way donors might like. This is not to say donations won’t help, though. Volunteer brigades might benefit from money for new vehicles or computers, for example.

The sacrifices made by Australian volunteer firefighters have only added to the “firies” mythos. Fire services have been flooded with record numbers of applications. As the threat of bushfires increases, the national love affair with volunteer firies is likely to only intensify.

Which is something no elected politician would be wise to ignore.

Vietnam’s Trade Surplus With US Jumps as Exports Surge and China Imports Hit Record

Vietnam’s Trade Surplus With US Jumps as Exports Surge and China Imports Hit Record  Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns

Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Indian Refiners Scale Back Russian Oil Imports as U.S.-India Trade Deal Advances

Indian Refiners Scale Back Russian Oil Imports as U.S.-India Trade Deal Advances  South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom

South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom  Yen Slides as Japan Election Boosts Fiscal Stimulus Expectations

Yen Slides as Japan Election Boosts Fiscal Stimulus Expectations