In response to the ongoing coronavirus emergency, on January 31, Chinese billionaire Jack Ma pledged the equivalent of US$144 million for medical supplies for Wuhan and Hubei as well as $14 million to help develop a vaccine. Just a few months ago, the former teacher had left the reins of a company of more than 100,000 employees, valued $450 billion, stating that he wanted to devote himself to philanthropy in the field of education. The emergence of the coronavirus threat showed his commitment to supporting public-health efforts as well.

In China, public figures have long since practised philanthropy – understood as “voluntary action for the public good” – often quietly. But given the magnitude of Jack Ma’s fortune, 21st in the world at approximately $43 billion, this decision indicates that Chinese philanthropy is at a historic turning point.

The revival of a thousand-year-old philanthropic tradition

Confucius, bronze. Gratitude and societal harmony are at the heart of Confucian thought. Wikimedia

One of the often-overlooked aspects of Chinese capitalism is the relative absence of private philanthropy on the part of the wealthy classes toward the most modest, until recently. Historically, however, the country has a tradition of generosity dating back more than 3,000 years, echoed by Confucianism. This tradition stagnated after 1949, in the early years of the People’s Republic: nationalisation of assets; foreign organisations dissolved or expelled from the territory. The socialist state had to provide for social needs and private initiatives were discouraged.

This chronology contrasts sharply with US economic history, where philanthropy emerged early on as a remedy for the social ills of laissez-faire capitalism in the Gilded Age.

Philanthropy served for over a century as “soft power” for the countries that practised it. Historical examples abound, as in the Cold War when it was used by the West to fight Marxism. The developing world today is a vast area of multiple philanthropic influences, invoking the pursuit of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

There is already a growing number of researchers of Chinese origin in the academic community dedicated to nonprofits and philanthropy (ARNOVA 2019 conference), and China is the subject of more extensive research.

Since the “open door” policy under Deng Xiaoping, China has experienced tremendous growth, which generated wealth but also more inequalities. The first private foundations flourished in the 1980s and ‘90s in attempt to halt this process and assist the state in its social spending. It was not until 1994 that the compatibility between philanthropy and socialism was officially admitted. Today, we are witnessing a real renaissance of the spirit of private philanthropy in the country.

Multiplication of billionaire philanthropists

The proliferation of Chinese philanthropists is directly linked to the rise of fortunes. In 2017, there were 373 billionaires in mainland China (the second largest concentration in the world after the 585 billionaires living in the United States), including 89 new individuals, an average of nearly two new billionaires every week. Their number slightly decreased in 2018, in line with the global market downturn, after five years of continuous growth.

Among rising self-made entrepreneurs, some influential national figures want to inspire a new generation of philanthropists.

Dr. Charles Chen Yidan, founder of the Yidan Prize for education. Yidan Prize Foundation

Dr. Charles Chen Yidan, co-founder of Tencent, left the company in 2013 after becoming one of the wealthiest men in the country, to devote himself to promoting education. The Yidan Prize ($3.8 million) is the world’s most generous award for educational research.

Another prominent figure is Ms. He Quiaonv, who in 2017 made a $1.5 billion pledge for biodiversity conservation, the largest donation ever for this cause.

Tax incentives for philanthropy have recently been increased. Individuals can deduct donations up to 30% of their taxable income, and businesses up to 12% of their annual profits.

Observatories of philanthropy

Research is expanding on Chinese philanthropy, as are institutions aimed at supporting the growth of the sector and training executives of new foundations.

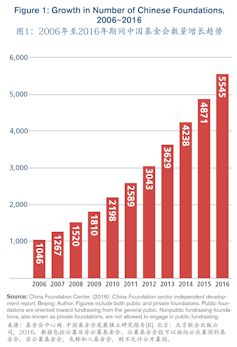

Growth in Number of Chinese Foundations (2006–2016). China Foundation Center, GCPI, Author provided

The China Foundation Center counted 5,545 foundations (endowed by wealthy individuals or using an annual public fund) in 2016, a figure that has more than quadrupled (+430%) in a decade since 2006. Their number then grew to 6,322 foundations in 2017 and 7,048 foundations in 2018. In 2014, their total gifts amounted to 102 billion yuan ($16.7 billion).

On the American side, Harvard University created a database to gather the most accurate data possible on Chinese philanthropy. It also offers several high-level trainings for leaders in this emerging field.

The number of Sino-American foundations listed in the US has quadrupled since 2000 to reach 1,300 entities in 2014. Bilateral cooperation is underway in attempt to align the interests and strategies of the two global philanthropic giants.

The China Global Philanthropy Institute was founded in 2015 by five Chinese and American philanthropists, including Bill Gates and Ray Dalio. The objective is to inspire others by “bringing out exemplary philanthropists and professional leaders in the philanthropic sector”, with a national and international dual focus. To this end, the Institute relies on a triptych of academic training, support for good practices, and study tours.

Moreover, the China Philanthropy big data Research Institute was launched in 2019 to mobilise the entire field of science and technology, including artificial intelligence, in favour of charitable activities with a stated intent for international cooperation.

These steps are aligned with China’s more general activism, which seeks prominence in the field of technology applicable to financial transactions via the imminent adoption of a digital currency or mastery of the blockchain.

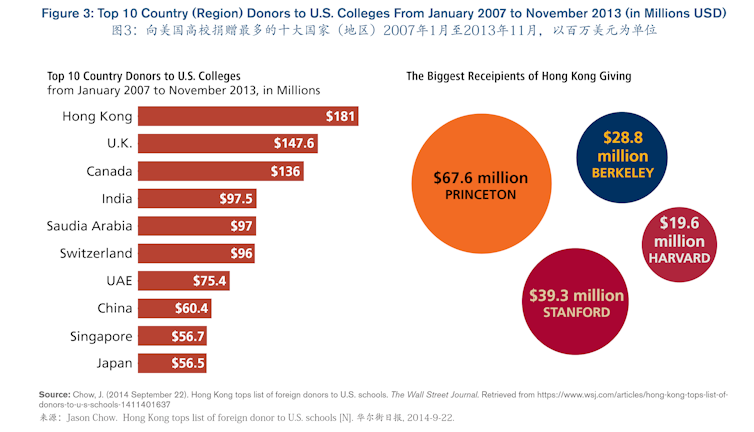

International giving to American universities (2007–2013), Jason Chow, Wall Street Journal, September 2014. Infographics GCPI, Author provided

A predictable international projection

Greater China, including Hong Kong, is already the main source of external funding to American universities through donations made by alumni, far ahead of traditional sources such as the United Kingdom and Canada. These exchanges also foster criticism in a broader context of tension between China and the United States, which affects universities.

To date, Chinese foundations have made international donations on all continents, especially in response to natural disasters. A dozen have even established offices or pilot projects abroad.

On the world stage, China intervenes more visibly than before through its foreign direct investments and official development aid, particularly in Africa.

President Xi Jinping’s thought on “socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era” include specific guidelines for diplomats called to build a “shared future for mankind”. If the authorities deployed a similar vision to direct the huge potential for philanthropic flows outward with equal long-term determination, there is no doubt that China will rise to the status of “great philanthropic power”.

Foresighted world influence

Although the great masses of Chinese philanthropy are still contained within national borders, all the ingredients are now there for its exponential international projection. This will likely have two consequences.

On one hand, the landscape of international philanthropy will be influenced by the increased presence of Chinese actors – yet no one currently knows what orientations they will favour. How will they fit into existing peer networks? How will they contribute to the emergence of a global philanthropic infrastructure?

How will this rise and the redistribution of power within the global philanthropic ecosystem be managed, given that the field has traditionally been under strong Western influence through its cardinal values, its financial networks, and its operational modes?

Symmetrically, internationally active Chinese foundations and philanthropists will probably nurture, enrich, and undoubtedly adjust their visions in contact with their foreign counterparts. Will this global sharing of experiences be a source of inspiration for the domestic philanthropic sector? How will China manage this two-way exchange of concepts, ideas, techniques, and perhaps even personnel?

Whatever the answers to these questions, China’s philanthropic sector will become a force to be reckoned with far beyond its borders in the 21st century. One must carefully look at this expansion today among the corollaries of the nation’s upward trajectory.

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate