In June 1348, people in England began reporting mysterious symptoms. They started off as mild and vague: headaches, aches, and nausea. This was followed by painful black lumps, or buboes, growing in the armpits and groin, which gave the disease its name: bubonic plague. The last stage was a high fever, and then death.

Originating in Central Asia, soldiers and caravans had brought bubonic plague – Yersina pestis, a bacterium carried on fleas that lived on rats – to ports on the Black Sea. The highly commercialised world of the Mediterranean ensured the plague’s swift transfer on merchant ships to Italy, and then across Europe. The Black Death killed between a third and a half of the population of Europe and the Near East.

This huge number of deaths was accompanied by general economic devastation. With a third of the workforce dead, the crops could not be harvested and communities fell apart. One in ten villages in England (and in Tuscany and other regions) were lost and never re-founded. Houses fell into the ground and were covered by grass and earth, leaving only the church behind. If you ever see a church or chapel all alone in a field, you are probably looking at the last remains of one of Europe’s lost villages.

The traumatic experience of the Black Death, which killed perhaps 80% of those who caught it, drove many people to write in an attempt to make sense of what they had lived through. In Aberdeen, John of Fordun, a Scottish chronicler, recorded that:

This sickness befell people everywhere, but especially the middling and lower classes, rarely the great. It generated such horror that children did not dare to visit their dying parents, nor parents their children, but fled for fear of contagion as if from leprosy or a serpent.

These lines could almost have been written today.

Although the death rate from COVID-19 is far lower than that of the Black Death, the economic fallout has been severe due to the globalised, highly-integrated nature of modern economies. Add to this our highly mobile populations today and coronavirus, unlike the plague, has spread across the globe in a matter of months, not years.

While the Black Death resulted in short term economic damage, the longer-term consequences were less obvious. Before the plague erupted, several centuries of population growth had produced a labour surplus, which was abruptly replaced with a labour shortage when many serfs and free peasants died. Historians have argued that this labour shortage allowed those peasants that survived the pandemic to demand better pay or to seek employment elsewhere. Despite government resistance, serfdom and the feudal system itself were ultimately eroded.

But another less often remarked consequence of the Black Death was the rise of wealthy entrepreneurs and business-government links. Although the Black Death caused short-term losses for Europe’s largest companies, in the long term, they concentrated their assets and gained a greater share of the market and influence with governments. This has strong parallels with the current situation in many countries across the world. While small companies rely upon government support to prevent them collapsing, many others – mainly the much larger ones involved in home delivery – are profiting handsomely from the new trading conditions.

The mid-14th century economy is too removed from the size, speed, and interconnectedness of the modern market to give exact comparisons. But we can certainly see parallels with the way that the Black Death strengthened the power of the state and accelerated the domination of key markets by a handful of mega-corporations.

Black Death business

The sudden loss of at least a third of Europe’s population didn’t lead to an even redistribution of wealth for everyone else. Instead, people responded to the devastation by keeping money within the family. Wills became highly specific and wealthy businessmen, in particular, went to great lengths to ensure that their patrimony was no longer divided up after death, replacing the previous tendency to leave a third of all their resources to charity. Their descendants benefited from a continued concentration of capital into a smaller and smaller number of hands.

At the same time, the decline of feudalism and the rise of a wage-based economy following peasant demands for better labour conditions benefited urban elites. Being paid in cash, rather than in kind (in the granting of privileges such as the right to collect firewood), meant that peasants had more money to spend in towns.

This concentration of wealth greatly accelerated a pre-existing trend: the emergence of merchant entrepreneurs who combined trade in goods with their production on a scale only available to those with significant sums of capital. For example, silk, once imported from Asia and Byzantium, was now being produced in Europe. Wealthy Italian merchants began to open silk and cloth workshops.

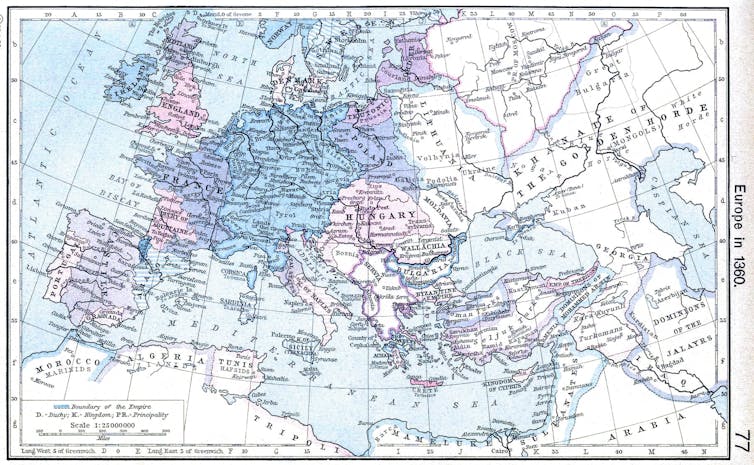

Europe in 1360. Wikimedia Commons

These entrepreneurs were uniquely positioned to respond to the sudden labour shortage caused by the Black Death. Unlike independent weavers, who lacked the capital, and unlike aristocrats, whose wealth was locked up in land, urban entrepreneurs were able to use their liquid capital to invest in new technologies, compensating for the loss of workers with machines.

In southern Germany, which became one of Europe’s most commercialised areas in the late 14th and 15th centuries, companies such as the Welser (which later ran Venezuela as a private colony) combined growing flax with owning the looms on which workers span that flax into linen cloth, which the Welser then sold. The trend of the post-Black Death 14th and 15th centuries was a concentration of resources – capital, skills, and infrastructure – into the hands of a small number of corporations.

The age of Amazon

Rolling forward to the present, there are some clear similarities. Certain large organisations have stepped up to the opportunities provided by COVID-19. In many countries across the world, entire ecologies of small restaurants, pubs and shops have suddenly been closed down. The market for food, general retail and entertainment has gone online, and cash has pretty much disappeared.

The percentage of calories that restaurants provided has had to be rerouted through supermarkets, and much of this supply has now been taken up by supermarket chains. They have plenty of large properties and lots of staff, with the HR capacity to recruit more rapidly, and there are many underemployed people who now want jobs. They also have warehouses, trucks and complex logistics capacity.

The other big winner has been the giants of online retail – such as Amazon, who run a “Prime Pantry” service in the US, India and many European countries. High street shops have been suffering from price and convenience competition from the internet for years, and bankruptcies are regular news. Now, much “non-essential” retail space is closed, and our desires have been re-rerouted through Amazon, eBay, Argos, Screwfix and others. There has been a clear spike in online shopping, and retail analysts are wondering whether this is a decisive move into the virtual world, and the further dominance of big corporations.

Keeping us distracted as we wait at home for our parcels is the streaming entertainment industry – a market sector which is dominated by big corporations including Netflix, Amazon Prime (again), Disney and and others. Other online giants such as Google (which owns YouTube), Facebook (which owns Instagram) and Twitter provide the other platforms that dominate online traffic.

The final link in the chain is the delivery companies themselves: UPS, FedEx, Amazon Logistics (again), as well as food delivery from Just Eat and Deliveroo. Through their business models are different, their platforms now dominate the movements of products of all kinds, whether your new Toshiba branded Amazon Fire TV, or your stuffed crust from Pizza Hut (a subsidiary of Yum! Brands, which also owns KFC, Taco Bell and others).

The other swing to corporate dominance has been the move away from state-backed cash towards contactless payment services. It’s obviously a corollary of online marketplaces, but also means that the money moves though big corporations that take their slice for moving it. Visa and Mastercard are the largest players, but Apple Pay, PayPal, and Amazon Pay (again) have all seen increases in their transaction volume as cash sits unused in people’s purses. And if cash is still imagined to be a vector for transmission, then retailers won’t take it and customers won’t use it.

Small business has taken a really decisive hit across a wide range of sectors as COVID-19, like the Black Death, results in big companies gaining market share. Even those working at home to write pieces like this are working on Skype (owned by Microsoft), Zoom and BlueJeans, as well using email clients and laptops made by a small number of global organisations. Billionaires are getting richer while ordinary people lose their jobs. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s CEO, has increased his wealth by US$25 billion since the start of the year.

But this is not the whole story. The other big trend in the response to the virus has been the strengthening of the power of the state.

Governing pandemics

At a state level, the Black Death caused the acceleration of trends towards centralisation, the growth of taxation, and government dependence upon large companies.

In England, the declining value of land and consequent falls in revenue prompted the crown – the country’s biggest landowner – to attempt to cap wages at pre-plague levels with the 1351 Statute of Labourers, and to impose additional taxes upon the populace. Previously, the government was expected to fund itself, only imposing taxes for extraordinary expenses such as wars. But the post-plague taxes set a major precedent for government intervention in the economy.

These governmental efforts were a significant increase in the crown’s involvement in people’s daily lives. In subsequent plague outbreaks, which occurred every 20 years or so, movement began to be restricted through curfews, travel bans, and quarantines. This was part of a general concentration of state power and the replacement of the previous regional distribution of authority with a centralised bureaucracy. Many of the men running the post-plague administration, such as the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, were drawn from English merchant families, some of which gained significant political power.

Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, founder of the Medici Bank. Wikimedia Commons

The most outstanding example of this was the de la Pole family, who in two generations went from being Hull wool merchants to earls of Suffolk. With the temporary collapse of international trade and finance after the Black Death, Richard de la Pole became the crown’s greatest lender and an intimate of Richard II. When Italian mega-companies re-emerged in the late 14th and 15th centuries, they also benefited from the crown’s ever-growing reliance upon merchant companies. The Medici family, who eventually came to rule Florence, are the most striking example.

Merchants also gained political influence by purchasing land, the price of which had fallen after the Black Death. Land ownership allowed merchants to enter the land-based gentry or even the aristocracy, marrying their children to the sons and daughters of cash-strapped lords. With their new status, and with the help of influential in-laws, the urban elites gained political representation within parliament.

By the end of the 14th century, the government’s extension of state control and its continued ties to merchant companies drove many nobles to turn against Richard II. They transferred their allegiance to his cousin, who became Henry IV, in the (vain) hope that he would not follow Richard’s policies.

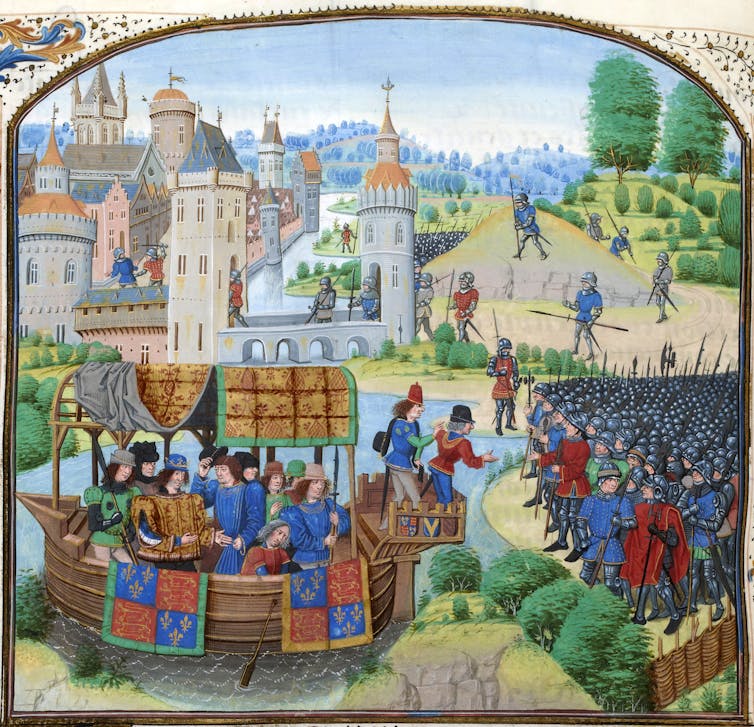

Richard II meeting with the rebels of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Wikimedia Commons

This, and the subsequent Wars of the Roses, generally depicted as a clash between the Yorkists and the Lancastrians, were actually partly driven by the nobility’s hostility towards the centralisation of government power. Henry Tudor’s defeat of Richard III in 1489 ended not only the war but also quashed any further attempts by the English baronage to regain regional authority, paving the way for the continued rise of corporations and central government.

The state we are in

The power of the state is something that we largely assume in the 21st century. Across the world, the idea of the sovereign nation has been central to the imperial politics and economy of the last few centuries.

But from the 1970s onwards, it became common among intellectuals to suggest that the state was less important, its monopoly of control within a given territory contested by multinational corporations. In 2016, of the largest 100 economic entities, 31 were countries and 69 were companies. Walmart was larger than the economy of Spain, Toyota larger than India. The capacity of these large companies to influence politicians and regulators has been clear enough: consider the effects of oil companies on climate change denial.

And since Margaret Thatcher, prime minister of the UK from 1979 to 1990, pronounced that she intended to “roll back the state”, more and more parts of previously state-owned assets now operate as companies, or as players in state engineered quasi-markets. Roughly 25% of the UK’s National Health Service, for example, is delivered through contracts with the private sector.

Across the globe, transport, utilities, telecommunications, dentists, opticians, the post office and many other services used to be state monopolies and are now run by profit-making companies. Nationalised, or state owned, industries are often described as slow, and in need of market discipline in order to become more modern and efficient.

But thanks to coronavirus, the state has come rolling back in again like a tsunami. Spending on a level which was mocked as “magic money tree” economics only a few months ago has been aimed at national health systems, addressed the problem of homelessness, provided universal basic income for millions of people, and offered loan guarantees or direct payments to a host of businesses.

This is Keynesian economics on a grand scale, in which national bonds are used to borrow money backed by future income from taxpayers. Ideas about balancing the budget appear to, for now, be history, with entire industries now being reliant on treasury bailouts. Politicians the world over have suddenly become interventionist, with wartime metaphors being used to justify gigantic spending.

Less often remarked is the astonishing restriction on personal freedoms. The autonomy of the individual is central to neoliberal ideas. “Freedom loving peoples” are contrasted with those who live their lives under the yoke of tyranny, of states that exercise Big Brother surveillance powers over their citizens behaviour.

Yet in the last few months, states around the world have effectively restricted movement for the vast majority of people and are using the police and armed forces to prevent assembly in public and private spaces. Theatres, pubs and restaurants are closed by fiat, parks have been locked, and sitting on benches can get you a fine. Running too close to someone will get you shouted at by someone in a high vis vest. A medieval king would have been impressed with this level of authoritarianism.

The pandemic seems to have allowed the fiscal and administrative powers of big government to bulldozer arguments about prudence and liberty. The state’s power is now being exercised in ways that haven’t been seen since the second world war, and there has been widespread public support.

Popular resistance

To return to the Black Death, the growth in wealth and influence of merchants and big business seriously aggravated existing anti-mercantile sentiment. Medieval thought – both intellectual and popular – held that trade was morally suspect and that merchants, especially wealthy ones, were prone to avarice. The Black Death was widely interpreted as a punishment from God for Europe’s sinfulness, and many post-plague writers blamed the church, governments, and wealthy companies for Christendom’s moral decline.

William Langland’s famous protest poem Piers Plowman was strongly anti-mercantilist. Other works, such as the mid-15th century poem the Libelle of Englysche Polycye, tolerated trade but wanted it in the hands of English merchants and out of the control of Italians, whom the author argued impoverished the country.

As the 14th and 15th centuries progressed and corporations gained a greater share of the market, popular and intellectual hostility grew. In the longer term, this was to have incendiary results. By the 16th century, the concentration of trade and finance into the hands of corporations had evolved into a near-monopoly upon royal and papal banking by a small number of companies who also held monopolies or near-monopolies over Europe’s major commodities – such as silver, copper, and mercury – and imports from Asia and the Americas, especially spices.

Sistine Chapel ceiling, Vatican City, painted by Michelangelo between 1508 and 1512. Amandajm/Wikimedia Commons

Martin Luther was incensed by this concentration and especially the Catholic Church’s use of monopolistic firms to collect indulgences. In 1524, Luther published a tract arguing that trade should be for the common (German) good and that merchants should not charge high prices. Along with other Protestant writers, such as Philip Melancthon and Ulrich von Hutten, Luther drew upon existing anti-mercantile sentiment to criticise the influence of business over government, adding financial injustice to their call for religious reform.

The sociologist Max Weber famously associated Protestantism with the emergence of capitalism and modern economic thought. But early Protestant writers opposed multinational corporations and the commercialisation of everyday life, drawing upon anti-mercantile sentiment that had its roots in the Black Death. This popular and religious opposition eventually led to the break from Rome and the transformation of Europe.

Is small always beautiful?

By the 21st century we have become used to the idea that capitalist firms produce concentrations of wealth. Whether Victorian industrialists, US robber barons or dot com billionaires, the inequalities generated by business and its corrupting influence over governments have shaped discussion of commerce since the industrial revolution. For critics, big business has often been characterised as heartless, a behemoth that crushes ordinary people in the wheels of its machines, or vampirically extracts the profits of labour from the labouring classes.

As we have seen, the arguments between small business localists and those who favour corporations and the power of the state date back many centuries. Romantic poets and radicals bemoaned the way that the “dark satanic mills” were destroying the countryside and producing people who were no more than appendages to machines. The idea that the honest craftsman was being replaced by the alienated employee, a wage slave, is common to both nostalgic and progressive critics of early capitalism.

By the 1960s, the idea that there was some fundamental difference between small and large forms of business added environmentalism to these longstanding arguments. “The man” in his skyscraper was opposed to the more authentic artisan.

This faith in local business combined with a suspicion of corporations and the state have flowed into the green, Occupy and Extinction Rebellion movements. Eating local food, using local money, and trying to tilt the purchasing power of “anchor institutions” like hospitals and universities towards small social enterprises has become the common sense of many contemporary economic activists.

But the COVID-19 crisis questions this small is good, big is bad dichotomy in some very fundamental ways. Large scale organising has appeared to be necessary to deal with the huge range of issues that the virus has thrown up, and the states that appear to have been most successful are those which have adopted the most interventionist forms of surveillance and control. Even the most ardent post-capitalist would have to admit that small social enterprises could not fit out a gigantic hospital in a few weeks.

And though there are plenty of examples of local businesses engaging in food delivery, and a commendable amount of mutual aid taking place, the population of the global north is largely being fed by large supermarket chains with complex logistics operations.

After coronavirus

The long-term result of the Black Death was the strengthening of the power of big business and the state. The same processes are happening much more rapidly during the coronavirus lockdown.

But we should be cautious of easy historical lessons. History never really repeats itself. The circumstances of each time are unique, and it simply isn’t wise to treat the “lesson” of history as if it were a series of experiments that prove certain general laws. And COVID-19 will not kill a third of any population, so though its effects are profound, they will not result in the same shortage of working people. If anything, it has actually strengthened the power of employers.

The most profound difference is that the virus comes in the middle of another crisis, that of climate change. There is a real danger that the policy of bouncing back to a growth economy will simply overwhelm the necessity of reducing carbon emissions. This is the nightmare scenario, one in which COVID-19 is just a prequel to something much worse.

But the huge mobilisations of people and money which governments and corporations have deployed also shows that big organisations can reshape themselves and the world extraordinarily rapidly if they wish. This gives real grounds for optimism concerning our collective capacity to re-engineer energy production, transport, food systems and much else – the green new deal which many policy makers have been sponsoring.

The Black Death and COVID-19 seem to have both caused concentration and centralisation of business and state power. That is interesting to note. But the biggest question is whether these potent forces can be aimed at the crisis to come.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Eleanor Russell, PhD Candidate in History, University of Cambridge

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary