Across the broad sweep of history, it’s usually overly simplistic to talk about a single event as a “turning point”. This is especially the case in a conflict such as the one in Ukraine. So many factors – geopolitical, strategic and economic – can and will continue to influence the course of the war.

So it would possibly suit the situation better to describe the passage of Joe Biden’s funding bill through the US Congress as providing an “inflection point” – although it is almost certainly too early to tell for sure. Reports from the battlefield are that Russian troops, mindful of the prospect that within months Ukraine will be able to call upon significant supplies of new equipment and ammunition, are pushing hard to take more territory as quickly as they can.

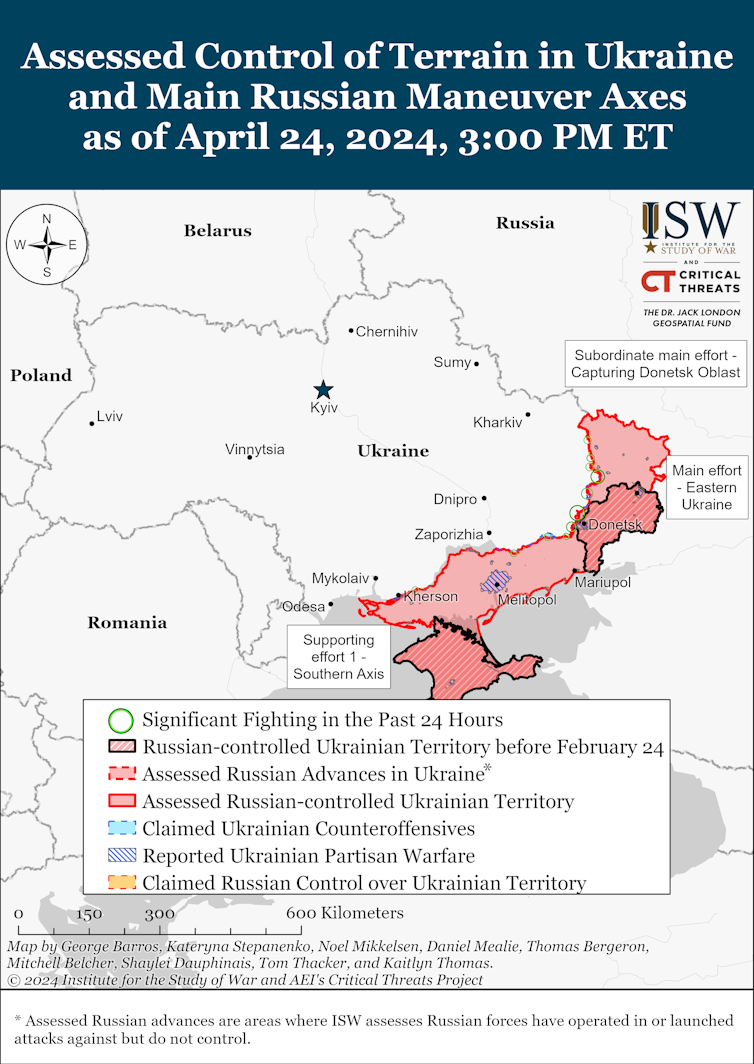

Basing its assessment on geolocated footage, the Institute for the Study of War has identified Russian advances along the frontlines in the eastern Donetsk region. The ISW estimates that Russia has captured 360 sq km of territory this year. Meanwhile Ukraine’s intelligence chief, Kyrylo Budanov, has said he believes Russia to be planning a fresh offensive in May.

At the same time, Ukraine has begun to attack Russian positions deep in the rear using long-range army tactical missile systems (ATACMS) provided by the US in March. It is doing so in the knowledge that there will be much more where that came from.

So perhaps this week has marked an inflection point in our coverage of the conflict. Last week we published a very stark piece by our regular contributors, Stefan Wolff of the University of Birmingham and Tetyana Malyarenko of the University of Odesa. The bleak headline: “Ukraine is losing the war and the west faces a stark choice: help now or face a resurgent and aggressive Russia” needs no explanation.

Within days, though, the blockage in Congress had been overcome and the House finally approved the provision of US$60– billion (£49 billion) in military aid to Kyiv. We asked Wolff to reassess the situation in light of this development. The headline on his latest piece, “US$60 billion in US military aid a major morale boost but no certain path to victory” presents a more hopeful, if measured, tone.

The state of the conflict in Ukraine as at April 2024. Institute for the Study of War

Wolff identifies a development which chimes with we have already noted above: “given that they are now secure in the knowledge that supplies arrive soon, Kyiv will be less compelled to ration ammunition as it has been forced to do recently.” Hence the use of the precious, stockpiled, ATACMS in the past few days.

Meanwhile, Tatsiana Kulakevich, a scholar of international relations at the University of South Florida, believes the passage of the US president’s funding bill is good for the US as well. She argues that a Russian victory in Ukraine in the absence of western – but more specifically US – assistance would send the wrong message to China which has territorial ambitions of its own. On the other hand, a Russian loss in Ukraine, aided by an engaged US and a united Europe, sends a clear message of deterrence to China.

Not only that, she argued, but this aid package has its own economic benefits for the US. The $60 billion will form part of a much larger boost for US defence spending to update its own arsenal. And it’s a potential win for Biden personally, as he campaigns for re-election in November. Most Americans support helping Ukraine in its fight against Putin’s Russia. Being seen to act with decisive strength and determination will do his image no harm as his rival Donald Trump fights his own battles against a string of criminal charges.

The nuclear risk

Other developments in April have included a series of drone attacks in the vicinity of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in souteastern Ukraine. The plant was captured by Russian forces in March 2022, about a week after the invasion began and has shut down in stages since – recently the final of six reactors at European’s largest nuclear plant was placed into a state of “cold shutdown”.

Now Putin wants to start the plant up again to begin generating electricity. Ross Peel, an expert in nuclear security and safeguards, particularly in war, at King’s College London, explains why this is so perilous. He writes:

This would greatly increase the danger of a nuclear accident, as operating reactors allow much less time before an accident occurs if they are damaged or their safety systems are interrupted. The pressure and temperature inside an operating reactor are also much greater, creating the potential for large explosions and the widespread dispersal of radioactive material.

And Zaporizhzhia doesn’t represent the only nuclear risk in Ukraine, writes Nino Antadze, an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Prince Edward Island in Canada. There are four nuclear plants in Ukraine as well as the abandoned shell of the Chernobyl plant which was the site of the worst nuclear accident in history and remains uninhabitable nearly 40 years on.

To wage war around these sites invites trouble, writes Antadze. When Chernobyl melted down in 1986, the International Atomic Energy Agency estimated that radioactive fallout affected an area of 150,000 sq km in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. You have to hope Putin keeps that in mind.

Fear and contagion

As campaigning season gathers momentum in Ukraine, both sides are beefing up conscription and enacting legislation to extend and toughen draft laws to get more men into uniform to boost troop numbers and relieve, in the case of Ukraine’s army at least, soldiers who have been at the frontlines for more than two years.

But it’s not just the two warring nations that are introducing or extending their conscription policies. A number of Nato members, including Latvia, have reintroduced conscription, and others such as Sweden and Estonia have extended it. Tony Ingesson, an expert in the politics of military decision-making at Lund University in Sweden, looks at the history of the draft – and the lengths many young people will go to to avoid it.

Another country which has been watching the progress of the war in Ukraine with trepidation is Georgia, which was itself invaded in 2008 and which has two breakaway provinces, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, that have been occupied by Russian troops ever since. By and large the Georgian people actively support Ukraine or are simply opposed to the conflict. But the country’s government is led by the pro-Russia Georgian Dream party.

New legislation introduced recently, the “foreign agents” law would mean that civil society groups and the media need register as being “under foreign influence” if they receive funding from abroad. It’s seen as a direct attack on NGOs operating in Georgia, writes Natasha Lindstaedt, an expert in authoritarian regimes at the University of Essex, who says it’s all part of the country’s drift towards autocracy under Georgian Dream.

A similar law was enacted in 2012 by Putin’s regime in Russia. But when Georgian Dream tried to introduce a similar measure last year it triggered huge popular protests, forcing the government to drop the bill. Lindstaedt believes the law would seriously damage Georgia’s prospects of becoming a member of the EU, something 80% of the country wants. So it’s hard to see this law being any more popular this time around.

Doomsday scenario

This week, Russia has vetoed a US-drafted resolution in the UN security council which called on countries to prevent an nuclear arms race in outer space, prompting the US to question whether Moscow had something to hide in this regard and the rest of the world to protest that having so many nuclear weapons on Earth is bad enough as it is.

For Becky Alexis-Martin, a lecturer in peace studies and pacifist academic at the University of Bradford, this message can’t be repeated too often. She sees an already dangerous world becoming ever more perilous as a result of the rising tensions between Russia and the west, the strife in the Middle East which could escalate into regional conflict and an increasingly assertive China.

Meanwhile, after decades in which the threat of an all-out nuclear war seemed have dissipated, many countries are now rearming, while some new player, Iran and North Korea among them, are openly pursuing their nuclear ambitions and look close to developing their own arsenals – if indeed they don’t already have them.

Alexis-Martin paints a disturbing picture of a new cold war which could turn hot at any time. A war in which everyone is a loser.

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings