Ten years ago, on April 20, 2010, the BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, killing 11 crew members and starting the largest ocean oil spill in history. Over the next three months, between 4 million and 5 million barrels of oil spewed into the Gulf of Mexico.

I was a member of the oil spill commission appointed by President Obama to investigate the causes of the disaster. Later, I served as a courtroom witness for the government on the effects of the spill. While scientists now know more about these effects, risks of deepwater blowouts remain, and the energy industry and government responders still have only very limited ability to control where the oil goes once it’s released from the well.

The spill commission found that multiple identifiable mistakes caused the blowout. Our report cast doubt over how safety was addressed across the offshore oil industry and the government’s ability to regulate it.

As the oil spill commission’s report showed, drilling ever deeper into the Gulf involved risks for which neither industry nor government was adequately prepared. The industry had felt so sure that a blowout would not happen that it lacked the capacity to contain it. Neither BP nor the government could do much to control or clean up the spill.

Safety improvements are threatened

The presidential commission recommended numerous reforms to reduce the risks and environmental damages from offshore oil and gas development. The industry developed systems to contain blowouts in deep water and has deployed them worldwide. Improvements in operational safety were made within companies and across the industry.

The Department of the Interior acted quickly to reorganize its units. It created a Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement to avoid conflicts of interests with its leasing, development and revenue collection responsibilities. After four years in development, the bureau issued new well control rules in 2016 governing drilling safety.

But despite progress on a number of fronts, Congress has not enacted legislation to improve safety or even raise energy companies’ ridiculously low liability limits for oil spills – currently just US$134 million for offshore facilities like the Deepwater Horizon. The Trump administration has reversed or relaxed safety reforms. It has loosened the safe pressure margins allowed in a well, dispensed with independent inspections of blowout protectors and removed requirements for continuous onshore monitoring of offshore drilling.

Some of these changes were ordered by political appointees over the recommendations of the safety bureau’s technical experts. While the bureau is charged with focusing singularly on safety and the environment, its director, Scott Angelle, has been a prominent proponent of the administration’s aggressive “energy dominance” strategy, ordering expanded oil production and elimination of costly regulations. Imagine the message this sends about priorities to people in government and industry who are responsible for ensuring safety.

Where contamination lingers

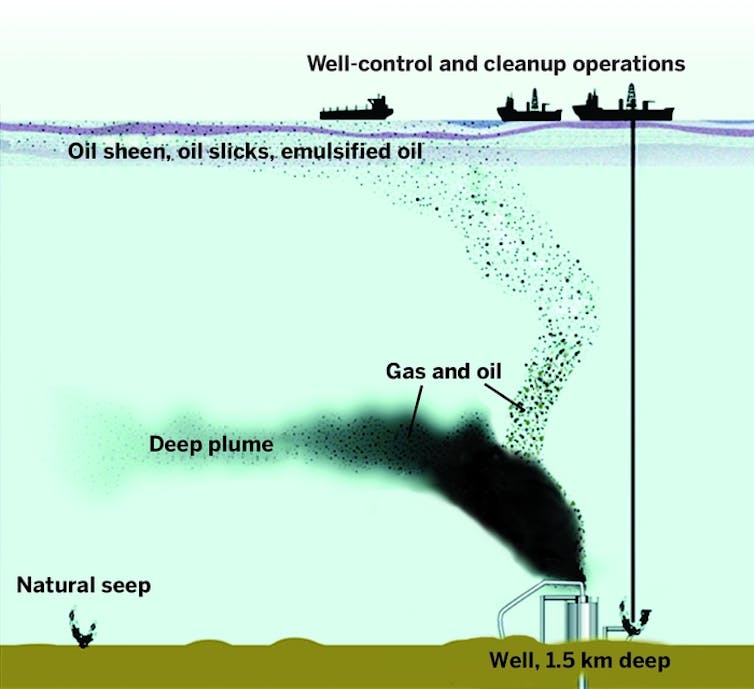

This conception of the deep plume shows how oil rose from the well. At a depth of 1 kilometer, bacteria consumed the oil. Adapted from Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/ES2013227

Before the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the deep Gulf of Mexico ecosystem was egregiously understudied in all respects, while a multi-billion-dollar industry. intruded into it. Now scientists know much more about what happens when large quantities of oil and gas are released in a seafloor blowout.

Scientists learned much about the effects of the spill through monitoring the blowout, assessing damages to natural resources and investigating the fate and effects of escaping oil. More has been spent on these studies and more results published than for any previous oil spill.

A substantial portion of oil released from the mile-deep well was entrained in a plume of droplets spreading out 3,000 feet below the Gulf’s surface. Footprints of contamination and effects extended far beyond the area where oil slicks were observed.

Two NASA satellites recorded day-by-day images of the Gulf after the blowout, from April 20 through May 24, 2010.

Nearly all of the oil released has since degraded. Populations of most affected organisms have recovered. But contamination lingers in sediments in the deep Gulf, and in some marshes and beaches where oil came ashore. Populations of long-lived animals the oil killed might not recover for decades. These include sea turtles, bottlenose dolphins, seabirds and deepwater corals.

And yet, as scientists synthesize results from this 10-year research initiative, very little practical advice is emerging about what can be done to respond more effectively to future blowouts from ever-deeper drilling in the Gulf.

Surely, we can more rapidly contain blowouts. The effectiveness of injecting chemical dispersants into the plume gushing from the well remains in debate. How much oil do dispersants keep from reaching the surface, where it threatens those working to stanch the blowout, as well as birds, sea turtles and coastal ecosystems? But the research has not revealed more effective approaches in controlling released oil.

Safety first is the big lesson

As I see it, the essential lesson from Deepwater Horizon is that industry and government should be putting their greatest energies into preventing operational accidents, blowouts and releases. Yet the Trump administration emphasizes increasing production and reducing regulations. This undermines safety improvements made over the past 10 years.

Furthermore, the price of crude oil – already low because of high fracked oil production in the U.S. – has declined drastically since the beginning of 2020. Saudi and Russian oil had already glutted the market when the coronavirus pandemic reduced oil consumption.

The federal government’s March 2020 oil and gas lease sale for the Gulf of Mexico yielded the lowest response in four years – $93 million in high bids, compared to $159 million in the previous round. To prop up the industry and maintain production, the Trump administration is seeking to lower royalty rates and store excess production in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

But as industry acts to cut its expenditures and downsize staff, will safety costs be a priority?

National energy policy was beyond the charge of the 2010 commission, but 10 years later, it is impossible to consider the future of offshore oil and gas without factoring in the need to eliminate net greenhouse gas emission within 30 years to limit climate change. Why would the United States consider expanding offshore exploration and drilling that might yield fossil fuels only 20 years from now?

Even in the historically developed Gulf of Mexico, rather than just “drill, baby, drill,” I believe the U.S. should be developing a realistic transition plan for phasing out offshore fossil fuel production. Such a strategy should encompass not only ensuring high standards for safety and industry responsibility for abandoned infrastructure during the drawdown, but also an economic evolution for the region, including opportunities for carbon sequestration and renewable energy production. We need to ensure that there will be a vibrant and productive Gulf long after we cease removing its oil.

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?

BTC Flat at $89,300 Despite $1.02B ETF Exodus — Buy the Dip Toward $107K?  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary