Around the world, the vast majority of people are flocking to cities not to dwell in their centres but to live in the new suburbs expanding their outer limits. Reflecting this, from 2000 to 2015, the expansion of urbanised land worldwide outpaced urban population growth. The result is unprecedented urban sprawl.

Expansive suburbs of single-family, freestanding housing are ubiquitous in countries such as Australia, the US and the UK. Most Australians still aspire to own a large detached house in the suburbs.

Public resistance to so-called infill development is unlikely to be overcome without a major change in how cities approach urban densification. We advocate greenspace-oriented development, or GOD, which provides substantial, public green spaces to serve surrounding higher-density neighbourhoods.

Greenspace-oriented development correlates urban densification with significant, upgraded public green spaces. Author provided

We love our leafy suburbs

The “Australian dream” of owning your own home is often automatically associated with a detached house on a block of land. It’s seen as a mark of having “made it”.

For instance, a study in Perth found that, if they had the money, 79% of people would prefer a separate dwelling and 13% a semi-detached option. Only 7% preferred flats, units or apartments.

Evidently, the suburban dream runs deep in the Australian cultural psyche. Australia is not alone in this. As a result of widespread preference for suburban living, globally we are not in the age of urbanisation but rather the age of suburbanisation.

Despite the enduring popularity of suburban life, several emerging crises threaten its dominance. These include the destruction of agriculturally productive and biodiverse land around expanding cities, ballooning commuting times and service and public transport infrastructure costs, and the concentration of socio-economic vulnerabilities in outer suburbs. These areas also have poorer access to jobs.

The problems of sprawl: contractors clear once biodiverse land on the edge of Perth for a new suburb. Author provided. Photo courtesy of Donna Broun, Richard Weller

Why infill efforts are failing

To limit urban sprawl, the emphasis in most cities worldwide is on increasing urban density. In pursuit of infill development, planning strategies have focused mostly on transit-oriented development. This approach focuses on higher-density development around public transport nodes and corridors.

Despite the widespread adoption of this ideology in Australia, many cities are not achieving their infill targets. In part, this is because transit-oriented development strategies suggest an “inflexible, over-neat vision” of cities at odds with their “increasing geographical complexity”.

Much of the infill that has been achieved is through indiscriminate and opportunistic subdivision of individual suburban lots by “mum and dad” investors. This “background infill” fails to achieve infill targets, does not reduce car use, erodes urban forests, and aggravates local communities. This has led to community resistance (the NIMBY factor) and what one council official referred to as a “public sullenness”.

Higher density with a green focus

The principles of transit-oriented development are well established and valid. However, we contend that we need a complementary strategy, greenspace-oriented development, for achieving infill development. This approach would correlate urban densification with substantial, upgraded public green spaces or parks that are relatively well served by public transport.

Greenspace-oriented development builds upon the now well-recognised array of benefits of green spaces for urban dwellers. Most importantly, it underpins approaches to making our cities more sustainable and liveable.

Australian suburbs do generally contain a reasonable number of parks. But these are typically underdesigned and underused. Many parks offer minimal amenity, often little more than large stretches of irrigated lawn and a scattering of trees.

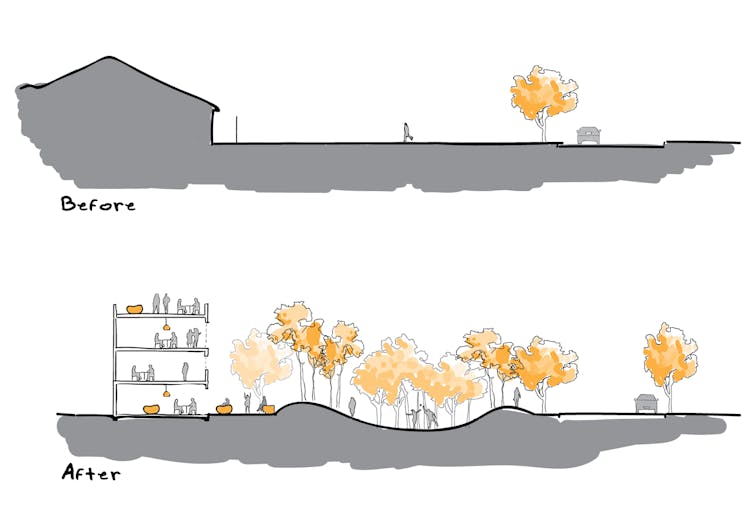

Before and after: in greenspace-oriented development, density and natural amenity are interwoven. Images courtesy of Robert Cameron. Author provided

We suggest redesigning parks to increase the naturalness, ecological function and diversity of active and passive recreational uses, which in turn can support higher-density urban areas. Indeed, it should increase the value of neighbouring real estate. With rezoning, this should enable greater local densification that is both commercially viable for developers and more attractive for residents.

Residents would then have an incentive to support well-designed infill development. When completed, each of these upgraded parks operates as a multifunctional, communal “backyard” for residents of a surrounding higher-density urban precinct.

Before and after: parks become multifunctional communal ‘backyards’ for people living at a higher density around the park. Author provided

The lure of suburbia clearly remains strong for people around the world. If planners are to deal with the problems of sprawl, they need to increase urban density in a way that resonates with the leafy green qualities of suburbia that most people desire (at very least in Australia).

Transit-oriented development ideology relies on a false presumption that residents will trade the benefits of nature for the benefits of urbanity. We require a new vision of urban densification that responds to the urban, societal and ecological challenges of the 21st century and aligns with people’s preference for suburban living near nature.

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  Every generation thinks they had it the toughest, but for Gen Z, they’re probably right

Every generation thinks they had it the toughest, but for Gen Z, they’re probably right  Columbia Student Mahmoud Khalil Fights Arrest as Deportation Case Moves to New Jersey

Columbia Student Mahmoud Khalil Fights Arrest as Deportation Case Moves to New Jersey  Office design isn’t keeping up with post-COVID work styles - here’s what workers really want

Office design isn’t keeping up with post-COVID work styles - here’s what workers really want  Yes, government influences wages – but not just in the way you might think

Yes, government influences wages – but not just in the way you might think  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Canada’s local food system faces major roadblocks without urgent policy changes

Canada’s local food system faces major roadblocks without urgent policy changes  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  6 simple questions to tell if a ‘finfluencer’ is more flash than cash

6 simple questions to tell if a ‘finfluencer’ is more flash than cash  Parents abused by their children often suffer in silence – specialist therapy is helping them find a voice

Parents abused by their children often suffer in silence – specialist therapy is helping them find a voice  The American mass exodus to Canada amid Trump 2.0 has yet to materialize

The American mass exodus to Canada amid Trump 2.0 has yet to materialize