After two months of ground war between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon, a negotiated ceasefire has been reached which for now should help to relieve civilian suffering. However, much will depend on both local and global politics.

The conflict between Israel and Hezbollah has raged since October 1. In that time, more than 3,768 Lebanese civilians have reportedly been killed and 15,699 wounded. On the Israeli side, 44 soldiers and 48 civilians were reportedly killed in what was the sixth Israeli incursion into Lebanon in 50 years.

The new ceasefire agreement superficially resembles the previous arrangements in southern Lebanon. It includes a commitment to UN security council resolution 1701 (which in 2006 called for an end to hostilities, withdrawal of Israeli and Hezbollah forces from the region, and the disarmament of Hezbollah), as well as the continued presence of UN peacekeepers and the deployment of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) in southern Lebanon.

On closer examination however, the agreement contains some critical differences. Three new elements have been introduced: the reestablishment of a monitoring and enforcement mechanism, a central role for the US and France, and the inclusion of the Military Technical Committee for Lebanon (MTC4L) in the implementation of resolution 1701.

The mechanism is not new but it is perhaps the only aspect of the UN’s peacekeeping mission that the Israel previously appeared to value. It existed from August 2006 until October 7 2023 in a forum known as “the tripartite meetings”.

The meetings were convened and chaired by the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (Unifil) and comprised regular meetings between representatives from the LAF and the Israeli Defence Force (IDF). Their aim was to prevent the escalation of security incidents on the de facto border with Israel known as the blue line. And they were recognised by successive UN secretaries general as making a crucial contribution to local security.

Initially, the tripartite meetings were composed of military officers and Unifil staff. The focus was on the tactical and operational aspects of monitoring the blue line and any violations of resolution 1701.

Now the meetings have a wider remit, which has political implications. They will provide a space for both Israel and Lebanon to report alleged violations of 1701. But the focus will predominantly be on dismantling Hezbollah and ensuring it cannot rearm.

It’s not currently clear how this committee will work with Unifil, which will host but not chair the meetings, and the UN security council to whom they report. Nor is it clear how violations will be investigated and punished – or by whom.

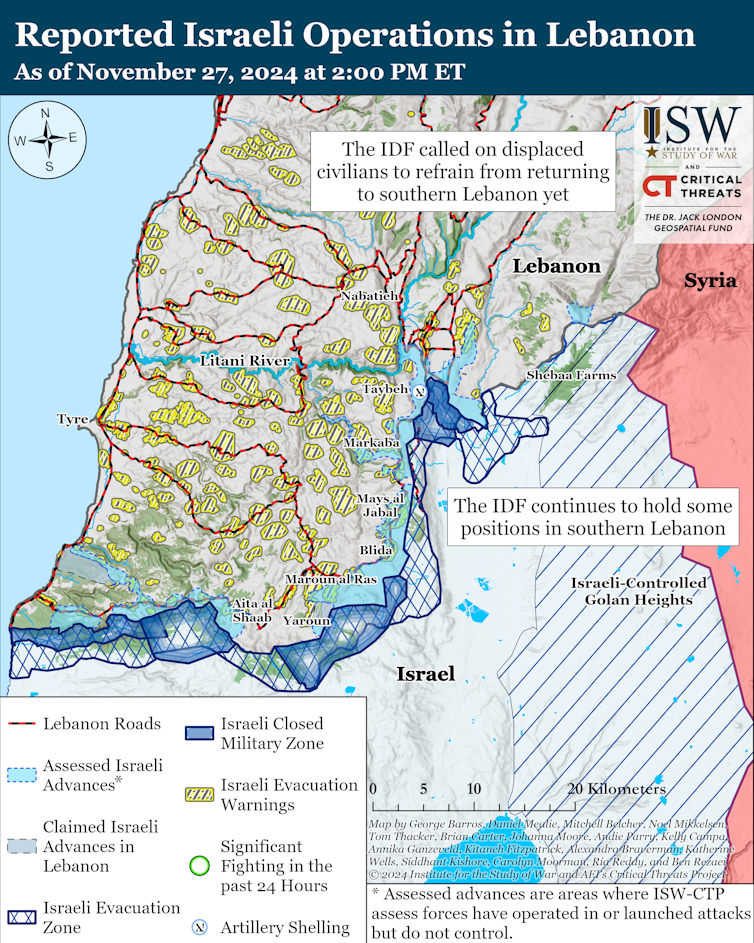

Contested territory: the state of the conflict as the ceasefire deal came into operation on November 27. Institute for the Study of War

The second innovation is the involvement of the MTC4L. This is a new initiative that aims to reinforce the capacity and mobility of the Lebanese armed forces, through training, recruitment and technical assistance. It is comprised of eight Nato states: Canada, France, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and the US.

In the new agreement, MTC4L is expected to help facilitate the deployment of 10,000 Lebanese soldiers to south Lebanon. This involvement elevates and formalises the level of cooperation between several Nato states and the LAF, potentially linking them more strongly to the success of the ceasefire agreement. The implications of this remain unclear.

The centrality of the US and France in this agreement is new. The US is tasked with chairing the mechanism and facilitating indirect negotiations between Israel and Lebanon on territorial disputes along the blue line. France is named throughout the agreement as a mediator, as well as playing a role in the MTC4L and the mechanism.

Nato countries leading, Unifil sidelined

During the 2006 ceasefire negotiations, Israel unsuccessfully called for a Nato deployment in south Lebanon. In the end a compromise was reached that involved making the Unifil mission more robust by greatly increasing the contribution of EU troops in 2006.

Israel’s earlier demands have now been met. It has succeeded in obtaining the direct involvement of the US, France and other prominent Nato states in the implementation of resolution 1701.

Israel has also managed to obtain a “letter of guarantee” from the US, recognising Israeli freedom of action on Lebanese soil, in the event of any attempt to strengthen Hezbollah or another hostile entity. This document is not an official part of the agreement and is regarded by Israel as being a “supplementary appendix”. As such, Israel has the luxury of an exit clause if the current arrangements don’t suit.

It’s no secret that Israel has never had confidence in Unifil. While the new agreement states that “Unifil’s work pursuant to its mandate will continue”, it’s not clear what UN peacekeepers’ contribution will actually amount to on the ground.

The US is chairing the mechanism, and the MTC4L is mandated to deliver humanitarian aid and assist with the return of internally displaced persons. These are the key roles that Unifil previously performed. Unifil also assisted the Lebanese armed forces in disarming Hezbollah and patrolling to search for weapons caches but it is now unclear whether this remains in their purview.

The new ceasefire agreement promises a precarious peace. Israel has succeeded in sidelining Unifil and drawing Nato countries more deeply into the conflict. By diluting responsibility across multiple stakeholders, the new agreement potentially creates competing lines of reporting and coordination problems. Israel’s letter of guarantee affords it unprecedented freedom of action in Lebanon which risks triggering further confrontation.

Perhaps the biggest problem with this agreement is that it applies technical solutions to a deeply political problem, with no direct political negotiation between the warring parties. Nato states risk being sucked into a conflict in which the protagonists themselves play little part trying to solve.

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings