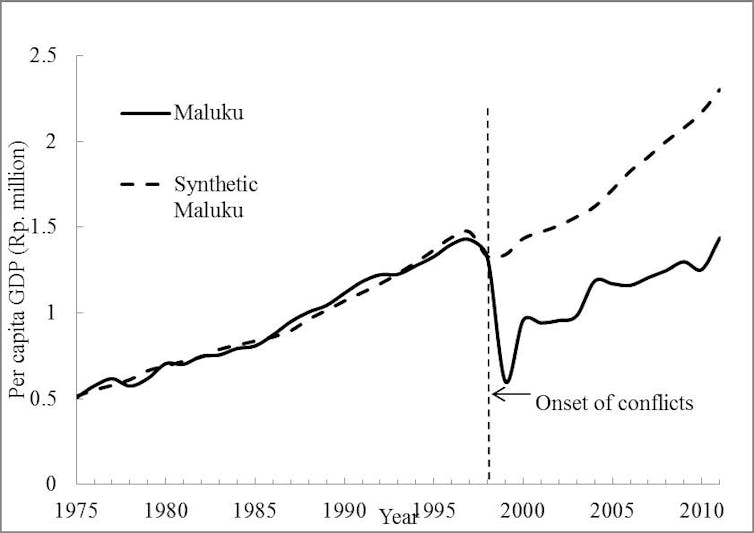

It has been almost 20 years since Indonesia faced socio-economic crises marked by internal conflicts. My recent study shows Maluku’s (and North Maluku’s) economy could have recorded much higher growth – an estimated 60.3% gap in 2011 – had the conflict not happened.

The economic indicator used is commonly translated to income per capita. This means the 60.3% gap would also translate into the estimated gap in income per capita. As this indicator also represents overall economic performance, the gap relates to lower business and market activities, and hence employment opportunities.

The province of Maluku (referring here to the province before its borders were redrawn in 1999) recorded one of the highest death tolls from internal conflict during the 1998–2000 period. Maluku recorded almost 5,000 deaths and hundreds of thousands of people were displaced. The region accounted for around half of all fatalities (9,399 deaths) from the country’s regional conflicts during this period.

However, before my study, the impact of this conflict on the province’s economy had not been calculated.

How to calculate the loss

Calculating this is not an easy task because the economic downturn in Maluku could be due to the Asian financial crisis rather than the localised unrest. Therefore, this study uses “synthetic” estimates of the economy in other regions that endured the same economic downturn but did not experience violent conflict.

The method creates a synthetic control using a combination of similar provinces in the pre-conflict period. The choice of control provinces is not subjective or arbitrary but driven by data.

After excluding provinces that also had high levels of conflict, the results show the pre-conflict per-capita economy of Maluku is best fitted by a weighted combination of four provinces: Bengkulu, North Sumatra, Jambi and South Sulawesi. A comparison of the trajectories of Maluku and its synthetic estimate shows how conflict affected the local economy.

The gap between synthetic Maluku and actual Maluku widened to more than the size of the actual Maluku economy in 1999. It means the actual economy was less than half what it could have been. The gap narrowed in 2000, but then widened during 2001–2003, meaning between 1999 and 2003 actual Maluku showed no signs of catching up with its synthetic control.

By 2011, the gap between the two Malukus had increased to 60.3% of the actual Maluku economy. The trajectories support the view that the persistence of violence, including the incident in 2004, is the reason the real economy trajectory is considerably affected.

Based on quick estimation for 2016, the gap between the two Malukus hasn’t changed much. This shows conditions in Maluku have stabilised in the past five years but this does not allow the economic trend to get back to where it used to be.

Gross Regional Product per capita: Maluku and synthetic Maluku, 1975–2011 (Rp million in 1993 prices)

Since the methodology could not directly explain the reason for the gap, the study further investigated this. Looking at other conflict areas in Indonesia, it could be argued the scale and length of the conflicts in Maluku have rendered the province unable to recover more quickly.

Plunging business confidence stunts growth

Another investigation looked at the conditions affecting Maluku’s economic performance – also known as growth determinants – in comparison to its synthetic counterpart.

In the period 1985-1998, the conditions between synthetic and actual did not have exactly the same trajectory but there was not much fluctuation in them. After the 1999 conflict, the relative value of manufacturing industry and infrastructure dropped only slightly compared to the synthetic counterpart. However, the relative value of investment and mining dropped considerably.

This trajectory indicates plunging business confidence. The relative value of infrastructure has slowly returned to its pre-crisis position after five years, boosted by government funding. But private sector investment, and hence private economic activities, did not return to Maluku after the crisis and conflicts.

One important lesson from this study is the potential impact of local conflict in Indonesia. This has become important considering competition among local political elites tends to raise tensions that could go beyond local elections.

According to a report by Cutura and Watanabe (2004), the conflict in North Maluku is also affected by a centuries-long political rivalry between the Sultans of Ternate and Tidore and political tensions related to the gubernatorial election at that time.

More reason to end conflict quickly

Although the study cannot conclusively say the results for Maluku were due to violent conflict alone, it shows the economy might have been able to bounce back if the violence had not continued for so long. The prolonged nature of the conflict, accompanied by significant violence across the province, seems to have eroded business confidence, in turn affecting the economic performance of Maluku.

Therefore, one implication of this study is that it is essential not only to prevent violent conflict, but also to make sure that when it does erupt, it does not last long. Addressing conflict quickly is important to restore business confidence and private investment and prevent long-term impact on the local economy.

But there is one danger of central government intervention. The conflict may change from a horizontal conflict (a dispute confined to the region) to a vertical conflict (a conflict with the central government). Therefore, any intervention to resolve a local conflict will require the involvement of community leaders.

The full version of this article is published in the December 2017 issue of the Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies.

Yogi Vidyattama does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yogi Vidyattama does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions

Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions  Silver Prices Plunge in Asian Trade as Dollar Strength Triggers Fresh Precious Metals Sell-Off

Silver Prices Plunge in Asian Trade as Dollar Strength Triggers Fresh Precious Metals Sell-Off  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom

South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom  Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility

Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility