Everton Football Club announced a milestone step towards moving from its historic Goodison Park home to a new stadium at Bramley Moore dock in Liverpool. When I saw this news my initial reaction was one of surprise. As a researcher in sustainable business models, surely spending £300m on a waterfront stadium is a significant risk in terms of sea level rise?

On paper, this is a fantastic opportunity for both the club and the city. For Everton it’s an opportunity to move to a large modern stadium befitting of a club which, under major shareholder Farhad Moshiri, has ambitions to become a leading footballing power. For the city of Liverpool, the development is a vital part of its regeneration programme, adding to its already UNESCO World Heritage-rated waterfront.

#DidYouKnow #LiverpoolWaters is one of the biggest #regeneration projects in Europe; costing £5.5 billion and spread over 150 acres? pic.twitter.com/88lleFdtoX

— Liverpool Waters (@PeelLivWaters) March 7, 2017

The exact implications of climate change for sea level rise are complex. There are simply too many variables. We don’t yet know whether the Paris Agreement is achievable, which means we don’t know how much the planet will warm by, let alone the precise consequences for sea level. But we have some good ideas.

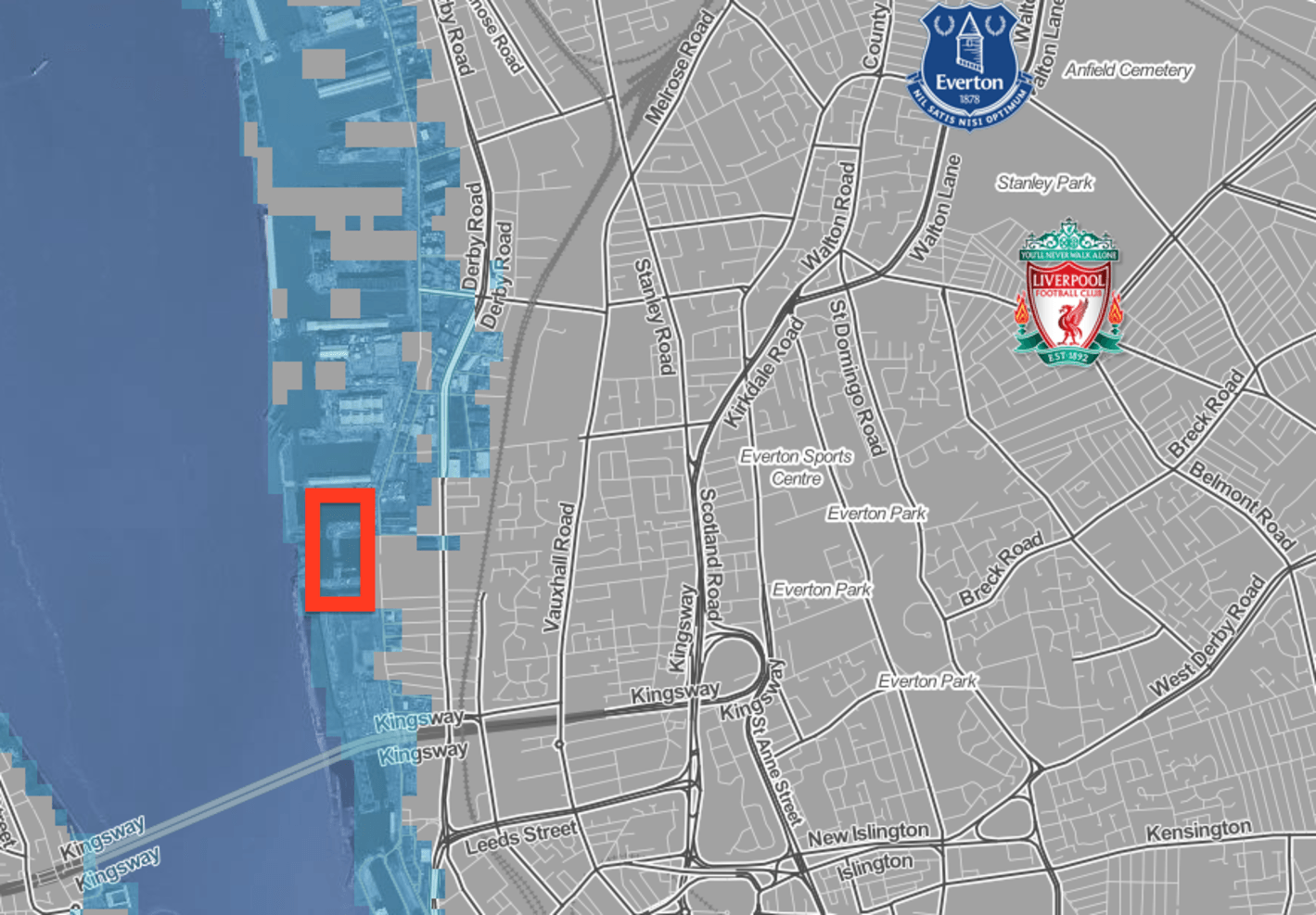

Recent research has shown that by the year 2100 sea levels could rise by two metres. That is only 83 years into the proposed stadium’s 200-year lease. And the Surging Seas website, which maps out scientific predictions of sea level rise, shows that 2℃ climate change would inundate the Liverpool docklands in the next 200 years or so.

Liverpool city centre, showing the two current football stadiums, and Bramley Moore dock (red box). After 2°C warming the light blue areas will eventually be permanently underwater. Climatecentral.org; data from Science/Dutton et al

The worst case scenario is even more worrying. Researchers at Liverpool John Moores University looked at what would happen if the sea were to rise seven metres, the same level as it was the last time the Earth was 1.5℃ hotter, and found much of the city would disappear under water.

Football clubs can’t ignore global warming

Of course, this won’t happen any time soon and few businesses are required to think in such long terms. New buildings are generally not designed to last for centuries, partly because it’s rare for a firm to last that long. This is one of the reasons why climate change is such a complex challenge for society – it simply does not comply with the time-frames of political or corporate shareholder decision-making.

But football clubs are different. Everton was founded in 1878 and has been at its current home of Goodison Park for 125 years. It will still be around to see 2℃ warming and beyond.

Although increasingly operated like businesses, football clubs remain institutions that are deeply important to many communities. For millions of people they are “the most important of the less important things”. Football clubs owe it to these people to think in the longer term.

Such thinking is starting to seep into the game. The popular book Soccernomics, for example, argues that a long-term footballing philosophy that underpins a club’s direction on the pitch, can prevent short-termism associated with changing managers every couple of years (something that politics too could benefit from).

Climate Change FC?

A truly responsible football club should embrace the challenge of overcoming climate change. They could start by recognising their own role, for instance the significant transport emissions of people travelling to matches.

I have conducted research in the past in which I benchmarked the environmental initiatives conducted by football clubs outside of the Premier League. While I found many clubs had carbon reduction initiatives typical of those found by leading “brands” in other industries, the majority had some way to go.

Considering most football clubs are effectively small and medium-sized enterprises, with few resources, this is perhaps to be expected. But it’s a missed opportunity. These clubs have the ability to engage with their communities on levels beyond that of perhaps even government or religion. They are already striving to do so on issues such as racism and homophobia. They should begin to highlight the climate change challenge too. Doing so could go a long way to justifying the increasing cost of following football, and could make a real difference in terms of our ability to mitigate the impacts of global warming.

Everton hasn’t won a trophy since 1995. The club’s fans, desperate for success, could be forgiven if they don’t let the far off implications of climate change deter them from supporting a state of the art new stadium. But whether they will look on this development so favourably in the coming decades remains to be seen. One can only hope the developers of this new stadium have undertaken a full climate change risk assessment – or have stocked up on sandbags.

Graeme Heyes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Graeme Heyes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Rise of the Zombie Bugs takes readers on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world

Rise of the Zombie Bugs takes readers on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world  GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’

GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’  How America courted increasingly destructive wildfires − and what that means for protecting homes today

How America courted increasingly destructive wildfires − and what that means for protecting homes today  How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus

How is Antarctica melting, exactly? Crucial details are beginning to come into focus  Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research

Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research  Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate

Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate  Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys

Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys  The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer  Extreme heat, flooding, wildfires – Colorado’s formerly incarcerated people on the hazards they faced behind bars

Extreme heat, flooding, wildfires – Colorado’s formerly incarcerated people on the hazards they faced behind bars  Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history

Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history  What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains

What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains  How to create a thriving forest, not box-checking ‘tree cover’

How to create a thriving forest, not box-checking ‘tree cover’  Burkina Faso and Mali’s fabulous flora: new plant life record released

Burkina Faso and Mali’s fabulous flora: new plant life record released