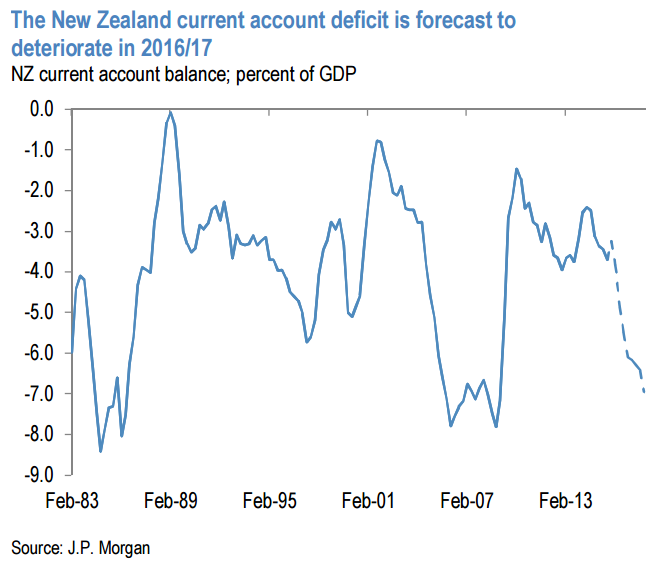

New Zealand's external imbalances have been a constant source of vulnerability through the last thirty years. Between 2010 and 2015 however, the issue had receded from view, with the high terms of trade, hangover from the late 2000s housing correction, and government belttightening holding the current account deficit in a benign (by New Zealand standards) range of around 3% of GDP. Over the prior decade the CAD had averaged over 4.5% of GDP, and at one point during the last housing boom in the mid-2000s neared 8%.

In 2016/17 return is expected to the bad old days of large current account deficits, which will be a headwind to NZD even if the RBNZ have reached the trough for the monetary policy cycle. Maintenance of solid domestic demand growth amid housing exuberance and trade drags should see the current account deficit position widen materially, to near 7% of GDP. Of most concern is that this will likely occur in an environment of rising US rates, which should throw a harsher spotlight on economies with external imbalances and dwindling relative yield compensation.

The contours of the deficit widening look similar to that seen in the middle of the last decade too, in that it is a private sector phenomenon, with the government accounts expected to stay in surplus. Indeed, recent data show that as at March 2015, the household sector's saving ratio had returned to negative territory (the savings rate was last negative in the period 2001-09) The implication is that the national borrowing requirement is not just growing, but is backing inherently riskier, housing-centric economic activity. At a minimum, this argues for more risk premium to be priced into NZD.

New Zealand’s current account comes back into focus

Thursday, November 26, 2015 11:01 PM UTC

Editor's Picks

- Market Data

Most Popular

Gold Prices Fall Amid Rate Jitters; Copper Steady as China Stimulus Eyed

Gold Prices Fall Amid Rate Jitters; Copper Steady as China Stimulus Eyed  Best Gold Stocks to Buy Now: AABB, GOLD, GDX

Best Gold Stocks to Buy Now: AABB, GOLD, GDX  FxWirePro: Daily Commodity Tracker - 21st March, 2022

FxWirePro: Daily Commodity Tracker - 21st March, 2022