For the first time, surfing is on the Olympic stage.

The surfing event will last for three days and has to run within the dates from July 25 to August 1. The reason for this window? Not all waves are created equal, and organizers and surfers will wait for the best day full of the best waves to hold the competition.

As a recreational surfer and physical oceanographer, I spend a lot of time thinking about waves. But for many people, this year’s Olympics will be their first time watching the sport. They might be wondering:

What generates the waves that surfers will ride at the Olympics? Where do the waves come from? And why will the new Olympians be surfing at Tsurigasaki Beach?

Wind creates waves

Think for a few seconds about what happens when you throw a stone into a serene pond. It creates a ring of waves – depressions and elevations of the water’s surface – that spread out from the center.

Waves in the ocean act similarly by propagating outward from where they are generated. The key difference is that the vast majority of ocean waves are formed by wind. As the wind blows over the surface of the water, some of the energy of the wind is transferred into the water, creating waves. The biggest and most powerful wind-generated waves are produced by strong storms that blow for a sustained period of time over a large area of the ocean.

The waves within a storm are usually messy and chaotic, but as they move away from the storm they grow more organized as faster waves outrun slower waves. This organization of the waves creates “swell,” or regularly spaced lines of waves.

Surfers will be competing at Tsurigasaki Beach on the east coast of Japan, where the waves break on sandbars. Pullwell/WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA

Seafloors break waves

As waves travel across the ocean, they don’t actually bring water with them – a wave from a storm 1,000 miles away isn’t made of water from 1,000 miles away. Waves are actually just energy moving from water molecule to water molecule. This energy doesn’t just move through the top layer of the ocean, either. Ocean waves extend far below the surface, sometimes as deep as 500 feet. When waves move into shallower water close to shore, they start to “feel” the seafloor as it pulls and drags on them, slowing them down. As seafloor gets shallower, it pushes upwards against the bottoms of waves, but the energy has to go somewhere, so the waves grow taller.

As the waves move toward shore, the water gets ever more shallow and the waves keep growing until, eventually, they become unstable and the wave “breaks” as the crest spills over toward shore.

It is only here, after a wave has traveled perhaps thousands of miles, that the surfing starts. To catch a wave, a surfer paddles toward shore until their speed matches that of the wave. As soon as the wave starts to break, the surfer stands up quickly and maneuvers the surf board with their feet and weight to ride the wave just ahead of the crashing lip.

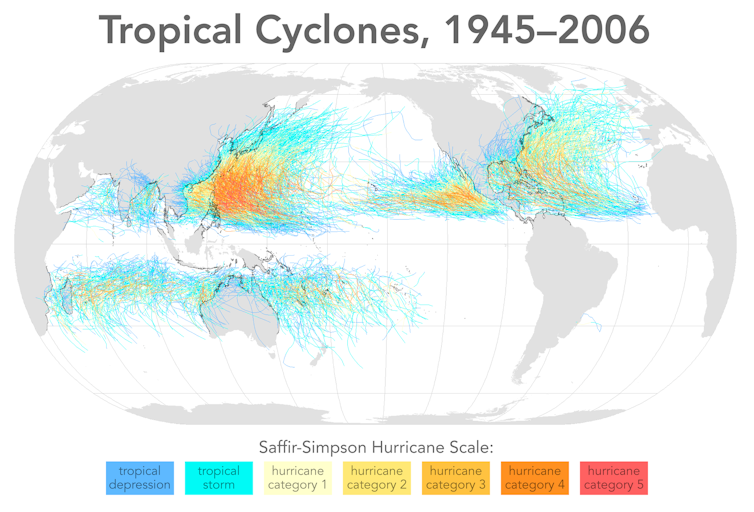

This map shows the tracks of all the tropical storms, typhoons and hurricanes that formed from 1945 to 2006. Note the hot spot of frequent, powerful storms south of Japan. Citynoise/WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA

Waves at the Olympics

The waves that surfers ride at Tsurigasaki Beach for the Olympics will be generated from one of two different types of wind: trade winds and typhoons.

Trade winds consistently blow around 11 to 15 mph (18 to 24 kph) in a band that stretches across the Pacific Ocean from approximately Mexico to the Philippines. These winds generate small “trade swells” that propagate northward toward the east coast of Japan and are usually a few feet tall when they arrive.

But if the surfers and spectators are lucky, a typhoon with wind speeds greater than 74 mph (119 kph) will be supplying powerful waves for the event. Typhoons are what hurricanes are called in much of Asia and are common near Japan and China during summer and fall. Winds in a typhoon are much stronger than the trade winds. Therefore, they generate much bigger waves. Olympic surfers obviously do not want a typhoon to hit Japan. What they want is for a typhoon to form about 500 to 1,500 miles (800 to 2,400 km) to the southeast of Japan and generate big waves that will hit the coast of Japan after traveling across the ocean for one to three days.

Based on the current weather and surf forecasts, it looks like just such a situation will happen. As of July 22, 2021, weather models are predicting that a tropical cyclone or typhoon will almost certainly develop to the southeast of Japan over the next few days, and the winds from this storm will send a powerful swell to the Olympics. Currently, models are predicting that the waves could be 7 feet (2.1 m) at Tsurigasaki Beach, just in time for the surfing event to start.

Once the swell from the trade winds or a far-off typhoon reaches Tsurigasaki Beach, it is the seafloor that will determine where the waves break. Tsurigasaki Beach is a “beach break,” which means that the seafloor is sand, rather than rocks or coral reef. There are a series of human-made rock walls, called groins, sticking out perpendicularly from the beach. These have been engineered to prevent sand from moving along the beach and are meant to slow erosion. These groins create shallow sandbars a few hundred yards from shore that incoming waves will break on. This is where the athletes will surf.

When you tune in to watch the surfing competition at the Olympics, marvel at the amazing skills of elite surfers, but remember too the far-off storms and the underwater sandbars that come together to create the beautiful waves.

Portions of this article originally appeared in an article published on Dec. 3, 2020.

Sally Warner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Sally Warner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Native American Groups Slam Trump’s Call to Restore Redskins Name

Native American Groups Slam Trump’s Call to Restore Redskins Name  Los Angeles Mayor Says White House Must Reassure Fans Ahead of FIFA World Cup

Los Angeles Mayor Says White House Must Reassure Fans Ahead of FIFA World Cup  Trump’s U.S. Open Visit Delays Final, Fans Face Long Security Lines

Trump’s U.S. Open Visit Delays Final, Fans Face Long Security Lines  Trump Set to Announce Washington D.C. as Host of 2027 NFL Draft

Trump Set to Announce Washington D.C. as Host of 2027 NFL Draft  Champions League final 2025: a battle for glory against a backdrop of money and fashion

Champions League final 2025: a battle for glory against a backdrop of money and fashion  Why Manchester City offered Erling Haaland the longest contract in Premier League history

Why Manchester City offered Erling Haaland the longest contract in Premier League history  Trump to Host UFC Event at White House on His 80th Birthday

Trump to Host UFC Event at White House on His 80th Birthday  Trump Booed at Club World Cup Final, Praises Pele as Soccer’s GOAT

Trump Booed at Club World Cup Final, Praises Pele as Soccer’s GOAT  From Messi to Mika Häkkinen: how top athletes can slow down time

From Messi to Mika Häkkinen: how top athletes can slow down time  Trump Draws Cheers at Ryder Cup as U.S. Trails Europe After Opening Day

Trump Draws Cheers at Ryder Cup as U.S. Trails Europe After Opening Day  US Reviewing Visa Denial for Venezuelan Little League Team Barred from World Series

US Reviewing Visa Denial for Venezuelan Little League Team Barred from World Series  Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push

Apple Eyes U.S. Formula 1 Broadcast Rights in Major Sports Streaming Push  ‘The geezer game’ – a nearly 50-year-old pickup basketball game – reveals its secrets to longevity

‘The geezer game’ – a nearly 50-year-old pickup basketball game – reveals its secrets to longevity  Trump Signs Executive Order Targeting Big-Money College Athlete Payouts

Trump Signs Executive Order Targeting Big-Money College Athlete Payouts  Trump Plans New Executive Order to Address Rising NIL Costs in College Sports

Trump Plans New Executive Order to Address Rising NIL Costs in College Sports