Earthquake scientists detected an unusual signal on monitoring stations used to detect seismic activity during September 2023. We saw it on sensors everywhere, from the Arctic to Antarctica.

We were baffled – the signal was unlike any previously recorded. Instead of the frequency-rich rumble typical of earthquakes, this was a monotonous hum, containing only a single vibration frequency. Even more puzzling was that the signal kept going for nine days.

Dickson Fjord is surrounded by steep mountains. Uwe Dedering / wiki, CC BY-SA

Initially classified as a “USO” – an unidentified seismic object – the source of the signal was eventually traced back to a massive landslide in Greenland’s remote Dickson Fjord. A staggering volume of rock and ice, enough to fill 10,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools, plunged into the fjord, triggering a 200-meter-high mega-tsunami and a phenomenon known as a seiche: a wave in the icy fjord that continued to slosh back and forth, some 10,000 times over nine days.

To put the tsunami in context, that 200-metre wave was double the height of the tower that houses Big Ben in London and many times higher than anything recorded after massive undersea earthquakes in Indonesia in 2004 (the Boxing Day tsunami) or Japan in 2011 (the tsunami which hit Fukushima nuclear plant). It was perhaps the tallest wave anywhere on Earth since 1980.

Our discovery, now published in the journal Science, relied on collaboration with 66 other scientists from 40 institutions across 15 countries. Much like an air crash investigation, solving this mystery required putting many diverse pieces of evidence together, from a treasure trove of seismic data, to satellite imagery, in-fjord water level monitors, and detailed simulations of how the tsunami wave evolved.

Before and after the landslide-tsunami. Before: Wieter Boone / Flanders Marine Institute; After: Danish military

This all highlighted a catastrophic, cascading chain of events, from decades to seconds before the collapse. The landslide travelled down a very steep glacier in a narrow gully before plunging into a narrow, confined fjord. Ultimately though it was decades of global heating that had thinned the glacier by several tens of meters, meaning that the mountain towering above it could no longer be held up.

Uncharted waters

But beyond the weirdness of this scientific marvel, this event underscores a deeper and more unsettling truth: climate change is reshaping our planet and our scientific methods in ways we are only beginning to understand.

It is a stark reminder that we are navigating uncharted waters. Just a year ago, the idea that a seiche could persist for nine days would have been dismissed as absurd. Similarly, a century ago, the notion that warming could destabilise slopes in the Arctic, leading to massive landslides and tsunamis happening almost yearly, would have been considered far-fetched. Yet, these once-unthinkable events are now becoming our new reality.

The ‘once unthinkable’ ripples around the world. (Video: Stephen Hicks; Kristian Svennevig; Thomas Lecocq; Alexis Marbeouf)

As we move deeper into this new era, we can expect to witness more phenomena that defy our previous understanding, simply because our experience does not encompass the extreme conditions we are now encountering. We found a nine-day wave that previously no one could imagine could exist.

Traditionally, discussions about climate change have focused on us looking upwards and outwards to the atmosphere and to the oceans with shifting weather patterns, and rising sea levels. But Dickson Fjord forces us to look downward, to the very crust beneath our feet.

For perhaps the first time, climate change has triggered a seismic event with global implications. The landslide in Greenland sent vibrations through the Earth, shaking the planet and generating seismic waves that travelled all around the globe, within an hour of the event. No piece of ground beneath our feet was immune to these vibrations, metaphorically opening up fissures in our understanding of these events.

This will happen again

Although landslide-tsunamis have been recorded before, the one in September 2023 was the first ever seen in east Greenland, an area that had appeared immune to these catastrophic climate change induced events.

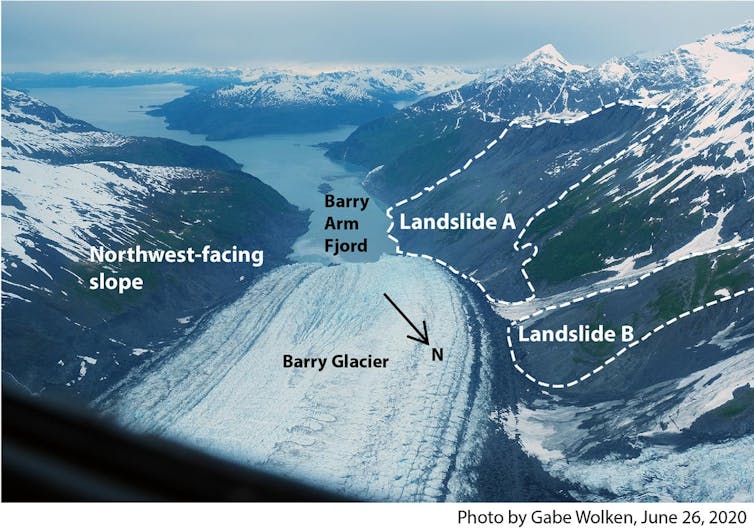

This certainly won’t be the last such landslide-megatsunami. As permafrost on steep slopes continues to warm and glaciers continue to thin we can expect these events to happen more often and on an even bigger scale across the world’s polar and mountainous regions. Recently identified unstable slopes in west Greenland and in Alaska are clear examples of looming disasters.

Landslide-affected slopes around Barry Arm fjord, Alaska. If the slopes suddenly collapse, scientists fear a large tsunami would hit the town of Whittier, 48km away. Gabe Wolken / USGS

As we confront these extreme and unexpected events, it is becoming clear that our existing scientific methods and toolkits may need to be fully equipped to deal with them. We had no standard workflow to analyse 2023 Greenland event. We also must adopt a new mindset because our current understanding is shaped by a now near-extinct, previously stable climate.

As we continue to alter our planet’s climate, we must be prepared for unexpected phenomena that challenge our current understanding and demand new ways of thinking. The ground beneath us is shaking, both literally and figuratively. While the scientific community must adapt and pave the way for informed decisions, it’s up to decision-makers to act.

The authors discuss their findings in more depth.

We combed through old botanical surveys to track how plants on Australia’s islands are changing

We combed through old botanical surveys to track how plants on Australia’s islands are changing  Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate

Thousands of satellites are due to burn up in the atmosphere every year – damaging the ozone layer and changing the climate  Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history

Lake beds are rich environmental records — studying them reveals much about a place’s history  Burkina Faso and Mali’s fabulous flora: new plant life record released

Burkina Faso and Mali’s fabulous flora: new plant life record released  An unexpected anomaly was found in the Pacific Ocean – and it could be a global time marker

An unexpected anomaly was found in the Pacific Ocean – and it could be a global time marker  Fungi are among the planet’s most important organisms — yet they continue to be overlooked in conservation strategies

Fungi are among the planet’s most important organisms — yet they continue to be overlooked in conservation strategies  Parasites are ecological dark matter – and they need protecting

Parasites are ecological dark matter – and they need protecting  Wildfires ignite infection risks, by weakening the body’s immune defences and spreading bugs in smoke

Wildfires ignite infection risks, by weakening the body’s immune defences and spreading bugs in smoke  Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research

Drug pollution in water is making salmon take more risks – new research  The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer

The UK is surprisingly short of water – but more reservoirs aren’t the answer  Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys

Swimming in the sweet spot: how marine animals save energy on long journeys  Ukraine minerals deal: the idea that natural resource extraction can build peace has been around for decades

Ukraine minerals deal: the idea that natural resource extraction can build peace has been around for decades  How ongoing deforestation is rooted in colonialism and its management practices

How ongoing deforestation is rooted in colonialism and its management practices  GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’

GesiaPlatform Launches Carbon-Neutral Lifestyle App ‘Net Zero Heroes’  Fertile land for growing vegetables is at risk — but a scientific discovery could turn the tide

Fertile land for growing vegetables is at risk — but a scientific discovery could turn the tide