In Simon Weckert’s Google Maps Hacks, a performance art work, a man pulls a little red wagon filled with 99 cell phones through Berlin. Drawing on the nostalgia of the Radio Flyer wagons and globes of my childhood, the piece seeks to disrupt Google Maps and to make a point about aggregated data by causing a virtual traffic jam. I remember conveying stuffed animals and favourite books around the block in my toy wagon, and travelling to my parents’ birthplaces by tracing a finger across the globe to a non-existent Ukraine (then a part of the Soviet Union).

Technology like Google Maps has reshaped our lives, from how we navigate to how we keep informed and work. Librarians like me face challenges in maintaining traditional means of accessing and delivering information to our users while embracing innovative media.

We appreciate the value of both analogue (print books, manuscripts, maps, globes) and digital resources like Google Maps, databases and digital archives. One format captures the history of institutions in general, and of libraries, in particular. The other allows for more equitable and experimental access. Yet, being an advocate for print can be a thankless task.

Students and their professors rely increasingly on libraries’ e-resources. As libraries closed during the pandemic, they were replaced with digital spaces. Yet, what is lost when entire libraries go online?

Technology vs. temporal experience

The value of print has been challenged before by technological innovations. At the turn of the twentieth century graphophone discs were predicted to replace written novels and plays for the spoken word. By mid-century, microcards were to revolutionize publishing and copyright; microfilm would allow for the large-scale reproduction of originals of materials. In the 21st century, low-circulating print books and high-demand ebooks are used as reasons to acquire ever more digital content.

What libraries rarely consider, though, is the extrinsic (artifactual) worth of their circulating holdings rather than their intrinsic (informational) value. Also, lost in the debate is the value of time: the time taken to browse shelves, to select a book and to read it and see traces of its use.

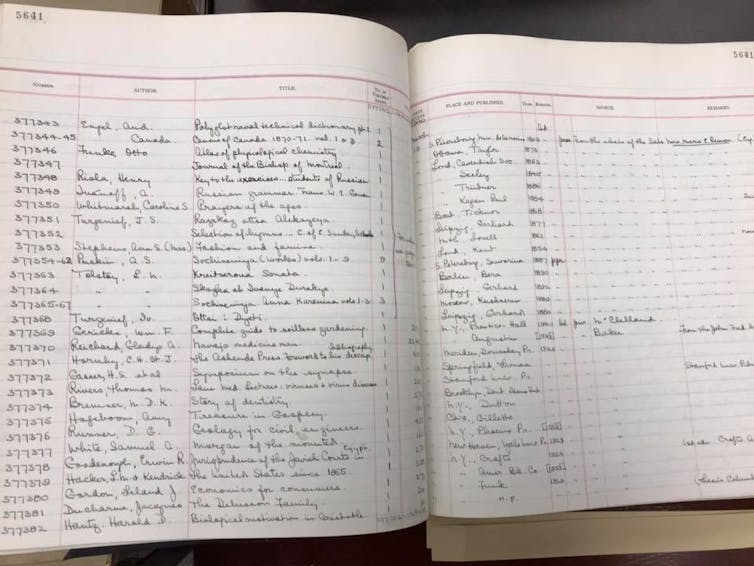

While exploring the history of the university’s library collection in our archives, I consulted dozens of old accession catalogues. These catalogues allow researchers to trace the library’s growth daily and yearly. Important information can be gleaned about titles in the collection, such as their bibliographical elements and provenance history.

A University of Toronto Library accession ledger shows who has had their hands on a hard copy of a book, giving a sense of the book’s history. (Ksenya Kiebuzinski), Author provided

One can discover details about the library’s history such as, books gifted by Queen Victoria, Frederick I (Grand Duke of Baden), the Meteorological Office in London, Trinity College in Cambridge or, more locally, the British historian Goldwin Smith of The Grange (today part of the Art Gallery of Ontario). This information cannot be discovered online. It requires meticulous research of half a million handwritten entries across a span of 50 years.

Social history of books

Where books come from is fascinating to researchers. Personal libraries provide insights into collectors’ lives, as do individual volumes donated to our institutions. These books often include physical traces associated with the original owners, such as signatures, dedications and book plates. We may see marginalia or doodles, newspaper clippings, photographs or flowers pressed inside as bookmarks. These discoveries help us map the social history of a particular volume. Unlike pristine new digital editions, older or donated books show signs of use that go beyond a circulation statistic.

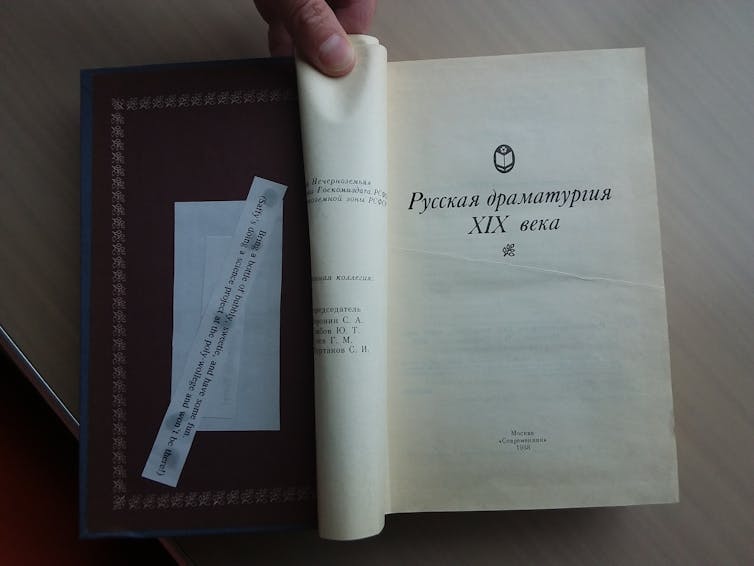

Our university library, for example, holds a book on 19th-century Russian drama with the following note pasted in: “Bring a bottle of bubbly, sweetie, and have some fun. (Saffy’s doing a science project at the poly-wollege and won’t be there!)”

A note inside a book on Russian theatre held at Robarts Library tells a story of not only the book but the life of one of its handlers. (Ksenya Kiebuzinski), Author provided

Other library books reveal ownership. The University of Toronto Library has a memoir of a Russian revolutionary (bound with several pamphlets by Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky) bearing the ink stamps of the Russian Branch of the Socialist Party in Quincy, Mass. These sample traces — a playful note inserted inside a book or an old ownership stamp —lead us to wonder what fun was had while Saffy was away, or curious about the history of Russians in Massachusetts and how the book got from Quincy to Toronto.

Such notes and stamps may be documented as notes in print or online catalogue records for rare books (not always), but rarely do traces of ownership — beyond an occasional autograph — get recorded for circulating material. While many libraries might own the same edition of a title, each copy may reveal something different about its former owners or readers.

Preserving library histories

In 2019, two graduate students of literature at the University of Virginia (UVA) worked frenetically to save their library’s card catalogue, slated to be discarded during a renovation. They discovered index cards that contained notes about physical volumes not reflected in the online catalogue. The catalogue also documents changes in publishing and reading preferences over time. It reveals how UVA’s collection was rebuilt following a fire in 1895 that largely destroyed it, and what volumes were held in the university’s founding years prior to the blaze.

Similarly, the University of Toronto library lost most of its collection following the great fire of 1890. While our card catalogue has been discarded, we have retained an original shelf list (a set of catalogue cards for books ordered by call number) for material acquired from 1890 until 1959. This will allow researchers to study seventy years of our library’s history.

How many stories and discoveries are yet to be related thumbing through these cards and browsing our book shelves? The Semantic Web and linked-data initiatives will surface library collections across the world, but machines cannot discover what is hidden in our card catalogues or lost forever when print copies are discarded or no longer collected.

SoftBank Shares Slide After Arm Earnings Miss Fuels Tech Stock Sell-Off

SoftBank Shares Slide After Arm Earnings Miss Fuels Tech Stock Sell-Off  Global PC Makers Eye Chinese Memory Chip Suppliers Amid Ongoing Supply Crunch

Global PC Makers Eye Chinese Memory Chip Suppliers Amid Ongoing Supply Crunch  Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race

Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race  SpaceX Seeks FCC Approval for Massive Solar-Powered Satellite Network to Support AI Data Centers

SpaceX Seeks FCC Approval for Massive Solar-Powered Satellite Network to Support AI Data Centers  OpenAI Expands Enterprise AI Strategy With Major Hiring Push Ahead of New Business Offering

OpenAI Expands Enterprise AI Strategy With Major Hiring Push Ahead of New Business Offering  AMD Shares Slide Despite Earnings Beat as Cautious Revenue Outlook Weighs on Stock

AMD Shares Slide Despite Earnings Beat as Cautious Revenue Outlook Weighs on Stock  Amazon Stock Rebounds After Earnings as $200B Capex Plan Sparks AI Spending Debate

Amazon Stock Rebounds After Earnings as $200B Capex Plan Sparks AI Spending Debate  Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine

Alphabet’s Massive AI Spending Surge Signals Confidence in Google’s Growth Engine  Palantir Stock Jumps After Strong Q4 Earnings Beat and Upbeat 2026 Revenue Forecast

Palantir Stock Jumps After Strong Q4 Earnings Beat and Upbeat 2026 Revenue Forecast  SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers

SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers  Oracle Plans $45–$50 Billion Funding Push in 2026 to Expand Cloud and AI Infrastructure

Oracle Plans $45–$50 Billion Funding Push in 2026 to Expand Cloud and AI Infrastructure  Nvidia, ByteDance, and the U.S.-China AI Chip Standoff Over H200 Exports

Nvidia, ByteDance, and the U.S.-China AI Chip Standoff Over H200 Exports  Nintendo Shares Slide After Earnings Miss Raises Switch 2 Margin Concerns

Nintendo Shares Slide After Earnings Miss Raises Switch 2 Margin Concerns  Anthropic Eyes $350 Billion Valuation as AI Funding and Share Sale Accelerate

Anthropic Eyes $350 Billion Valuation as AI Funding and Share Sale Accelerate  Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Says AI Investment Boom Is Just Beginning as NVDA Shares Surge

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Says AI Investment Boom Is Just Beginning as NVDA Shares Surge  Tencent Shares Slide After WeChat Restricts YuanBao AI Promotional Links

Tencent Shares Slide After WeChat Restricts YuanBao AI Promotional Links  Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised

Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised