We are still settling Australian cities on unceded Aboriginal lands. With the global agreement on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, development has finally come home to the developed world. Yet in Australia we still often proceed as if development goals are about foreign aid, somehow separate from our own development activities and civic responsibilities.

The Senate inquiry into the SDGs, for example, has been referred to the Department of Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. Three of the seven terms of reference relate to Australia’s Official Development Assistance program.

Reports that trade with Europe might be in jeopardy because of Australia’s failure to act responsibly on climate change – a commitment enshrined not just in the Paris Agreement but also in SDG 13: Climate Action – illustrate the naivety of thinking this country can carry on as usual while others tackle sustainable development.

Australia’s SDG indicator framework

The National Sustainable Development Council’s focus on transforming Australia is an important starting point. The NCDC draws on the SDG Progress Report to “highlight key trends and emerging issues for policy and decision-makers and communities across Australia”. But it doesn’t go far enough.

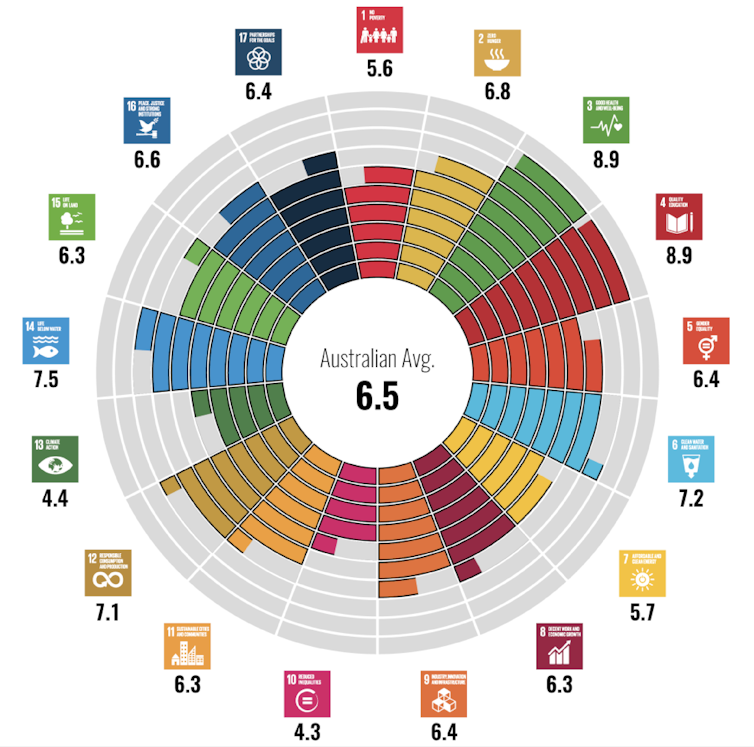

The focus is on targets and indicators that are deemed relevant and important for Australia. This is complemented by a wheel-of-fortune-style dashboard set of aggregated results across four key benchmarks.

The result is a colourful, largely unintelligible – albeit very well-intentioned – national SDG assessment.

Australia’s SDG Indicator Scorecard. NCDC

Looks like we get a C grade. But what does this actually say about Australian settlements?

Sanitised and complacent

The real issues facing Australia are sanitised and out of sight with a 6.5 score. With 90% of Australians living in urban areas, how does this assessment inform and transform the state of sustainable development in our cities?

A core sustainable development challenge for Australia is the spatial unevenness of its development – between cities and non-city regions, between the dominant cities (Sydney and Melbourne) and the rest, or between different suburbs within cities.

Our patchwork economy generates serious social inequities. The answer is not just to stimulate greater economic activity or spread the boom to “lagging” areas.

We need to recognise that the apparent success of the “bright patches” is often based on their exploitation of “dull patches”. Some areas are set up to be sacrifice zones that suffer, for example, the ill effects of resource extraction, heavy industry and waste disposal.

And some regions struggle not simply because they are physically distant, but because uneven provision of infrastructure has made them functionally distant. Prioritisation of certain regions over others and an over-reliance on infrastructure provision as a proxy for development are two issues that the nation needs to tackle to deliver the SDG agenda.

Do you know all 17 Sustainable Development Goals?

Beyond national silos

Australian cities rely on and impact upon these spaces and others far beyond their boundaries. Thus tackling SDG 11 on cities cannot be separated from tackling the other SDGs, including sustainably managing life on land (SDG 15), clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7) and life below water (SDG 14).

This means thinking not just about where and how cities access resources, but where their outputs go. For example, when China halted a major waste flow to its recycling plants this exposed the reliance of Australian cities on often distant facilities.

This demonstrates how cities are inextricably linked to spaces beyond their city limits, and the need for Australian cities to reduce and reuse as well as just recycle waste. It also illustrates the entwining of Australian settlement development with multiple spaces beyond our borders. Australia’s responsibility for sustainable development includes attention to the nation’s own urban heartlands as well as their impact on both neighbouring and distant countries.

Putting the SDGs to work in Australian cities

The SDGs can be mobilised to help achieve sustainable development, but we are not putting them to work in Australia. We stumble our way into the challenges of our climate of change, no more nationally self-aware it seems than before.

A new sustainable development approach is needed in Australia. An SDG ethic and compass must guide our direction so no one is left behind.

The SDGs are an invitation to take seriously the sustainable development challenges we face as a nation, and the implications of our actions for other nations. Rather than look for ways to reinforce our developed country privilege with a C grade report card, we could use the SDGs as a two-fold opportunity to:

1) ask the hard questions about the sustainability of our development

2) collectively explore transformative pathways, particularly within our cities.

Both suggest the importance of connecting more genuinely with Indigenous understandings of sustainability and living ethically on Country. And what do the SDG indicator frameworks and benchmarks tell us about our progress in our sovereign relationship with Indigenous people on whose unceded land we live and work?

We are not arguing for a more parochial agenda, or that international development is not important. Indeed, Australia could usefully follow the UK in positioning national science and research priorities within broader “global challenges”.

Rather, we are pointing to the risks of framing sustainable development issues as problems “over there”. This obscures both Australia’s own acute settlement problems and its role in creating problems “over there”.

What is needed is joined-up policy, planning and research that includes Australia within the frame as a sustainable development site, as well as a funding provider.

It could also include identifying Australia as a country in need: a nation that needs to better contribute to all the SDGs. In the case of SDG 13 on climate action, that need is glaring.

In Australia we need to make sure our identity does not include an implicit assumption that our home base is not in need of SDG attention – or only in certain areas. Many if not all aspects of development in Australia are maldevelopment, which calls for strong critical evaluation and action as much as in any other space. As a nation we can do much better.

Bank of Korea Holds Interest Rate at 2.50% as Growth Outlook Improves Amid AI Chip Boom

Bank of Korea Holds Interest Rate at 2.50% as Growth Outlook Improves Amid AI Chip Boom  Asian Stocks Rise on Nvidia Earnings Boost; Yen Weakens as BOJ Rate Outlook Clouds

Asian Stocks Rise on Nvidia Earnings Boost; Yen Weakens as BOJ Rate Outlook Clouds  Ecuador Raises Tariffs on Colombian Imports to 50% Amid Border Security Dispute

Ecuador Raises Tariffs on Colombian Imports to 50% Amid Border Security Dispute  PBOC Scraps FX Risk Reserves to Curb Rapid Yuan Appreciation

PBOC Scraps FX Risk Reserves to Curb Rapid Yuan Appreciation  Trump Warns Iran as Gulf Conflict Disrupts Oil Markets and Global Trade

Trump Warns Iran as Gulf Conflict Disrupts Oil Markets and Global Trade  BOJ Signals Possible April Rate Hike as Ueda Eyes Inflation and Wage Growth Data

BOJ Signals Possible April Rate Hike as Ueda Eyes Inflation and Wage Growth Data  Stock Market Movers: Dell, Block, Duolingo, Zscaler, CoreWeave, Autodesk, Rocket, MARA

Stock Market Movers: Dell, Block, Duolingo, Zscaler, CoreWeave, Autodesk, Rocket, MARA  Strait of Hormuz Oil and LNG Shipments Disrupted After U.S.-Israel Strikes on Iran

Strait of Hormuz Oil and LNG Shipments Disrupted After U.S.-Israel Strikes on Iran  MOEX Russia Index Hits 3-Month High as Energy Stocks Lead Gains

MOEX Russia Index Hits 3-Month High as Energy Stocks Lead Gains