“One of the reasons we lead the free world today is that we are a nation of immigrants.”

These words were delivered by Harry Truman to the US Congress in 1952 when he addressed the problem of aid for refugees who were fleeing “the oppressed countries of Eastern Europe.” Since then, US presidents have widely defined the United States as “a nation of immigrants,” regardless of their political ideology.

Donald Trump has broken this long-held tradition by running on an anti-immigration platform. He set the tone in his presidential announcement speech when he associated Mexican immigrants with drugs, crime and rape.

His anti-immigrant stance has been reflected in the policy of his administration since he became president. In February 2018, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the federal agency in charge of immigration, eliminated the phrase “America’s promise as a nation of immigrants” from its mission statement.

Recreating the savage “Other”

Even more significantly, President Trump has completely transformed presidential discourse on immigration by making immigrants the new face of a threatening “Other,” a primitive savage that has many of the features of the “Indians” of the American frontier myth.

Scholars such as Robert Ivie, Richard Drinon, Mark West and Christ Carey, Richard Slotkin, or Mary Stuckey have long demonstrated the relevance of the imagery of the savage “Other” in portraying America’s enemies in presidential rhetoric, during the Vietnam war, the Cold War, or the War on Terror, to name just the most recent ones.

It is the first time, however, that a modern US president has characterised immigrants as the enemies of an America ravaged by war on its own soil.

Frontier myth rhetoric

Just like the word Indian in the frontier myth, the term immigrant conflates an immense variety of individuals from different nations, situations, locations and with different motivations into a single undifferentiated mass constantly associated with crime, drugs and violence. Pennsylvania State University professor Mary Stuckey notes how during the Indian Wars, all native people were treated like enemies. It is the same for the immigrants today in Trump’s America.

In one of his first executive orders, just five days after his inauguration, President Trump linked undocumented immigration to “a significant threat to national security and public safety,” a threat of “acts of terror or criminal conduct” and a “clear and present danger to the interests of the United States.”

It does not matter that statistics did support his claims. For Trump and many Republicans, there is no distinction between killing and breaking the law. Committing “the federal crime of illegal entry” makes undocumented immigrants potential dangerous criminals.

This view reflects a conservative ideology that tightly intertwines law and morality: “Weak laws” mean weak morality. This threat is not limited to undocumented immigration: even asylum seekers at legal ports of entry have been treated like criminals, PBS recently reported. This ambiguity and confusion is also part of the president’s rhetoric.

A racialised enemy

Like the “Indian” in the Old West, the immigrant today is all the more feared by white America that he is cast as a racialised Other. President Trump has been called the “first white president”, and has a long history of racist comments.

The racist subtext of his immigration policy is clearly understood by his base, especially since it often comes to the surface. In January of 2018, for instance, Trump asked at a meeting with lawmakers why the United States should be accepting immigrants from Haiti and other “shithole countries” in Africa and elsewhere, and not more from nations such as Norway. This view is a return to the 19th-century American immigration system, which viewed immigration through the lens of a racial hierarchy.

Responses to Trump comments about ‘shithole countries’, Time magazine.

Domestic war and the lone hero

Like the frontier-era Indians, or the communists or the terrorists in more recent times, the immigrants represent the double threat of being both inside and outside the country, a country that is, according to Trump, ravaged by war.

From the mention of the “American carnage” in his inaugural address to his numerous references to towns, cities, communities “under siege” by a “ruthless gang [MS-13] that has violated our borders”, his favourite example of a criminal organisation supposedly made of foreigners, the president offers a gruesome view of a war being waged on the American soil. As with most metaphors employed by Trump, the war one is not subtle.

On June 31 he claimed on Twitter that he watched members of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency “liberating towns”:

“I have watched ICE liberate towns from the grasp of MS-13 & clean out the toughest of situations.”

Trump’s war narrative includes classic elements of “captivity” and “rescue” from the frontier myth. In his retelling, the heroic cavalry liberating the captives is the Immigration and Customs Enforcement service, and the solitary, heroic figure is Donald Trump himself.

Both the frontier narrative and Trump’s depiction of America are characterised by the absence of “safe zones” because the enemy is perceived as fluid, a perception illustrated by the president’s use of liquid metaphors: illegal immigrants are “pouring into our country”, refugees have “flooded in” and their “flow” must be stopped. This warrants the construction of a flood wall and the implementation of restrictive immigration policy.

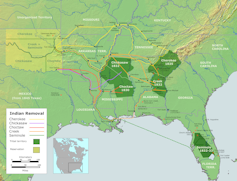

Map of the route of the ‘Trails of Tears’, depicting the route taken to relocate Native Americans from the South-eastern United States between 1836 and 1839. Background map from the Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 4. Nikater/Wikimedia

Tricksters

The immigrants resemble the frontier Indians in another important respect, both are considered inferior in technology; it is not their weaponry that constitutes a threat, but their sheer number. Without strong borders, warns the president, “millions and millions of people [would be] pouring through our country with all the problems that would cause with crime and schools.”

These baseless high numbers increase the fear effect by making immigrants an indistinguishable yet threatening mass. And like the First Nations, their potential conquest is possible through deception and trickery.

The American people, the president goes on, must be on guard against immigrants because those who “look so innocent” are “not innocent”. He further warns that “a single immigrant can bring in virtually unlimited numbers of distant relatives” and put “great strain on federal welfare”.

Barbaric practices

But the most important link between the mythical figure of the Native American and today’s American immigrants is their alleged savagery and violence through numerous accounts of massacres, torture, rape and mutilations.

The Vanishing Race, by Joseph Dixon (1914). In Trump’s rhetoric, the presence of today’s migrants on American soil echoes the threats posed by ‘hordes’ of yesterday’s First Nations. Tractatus/Flickr, CC BY-ND

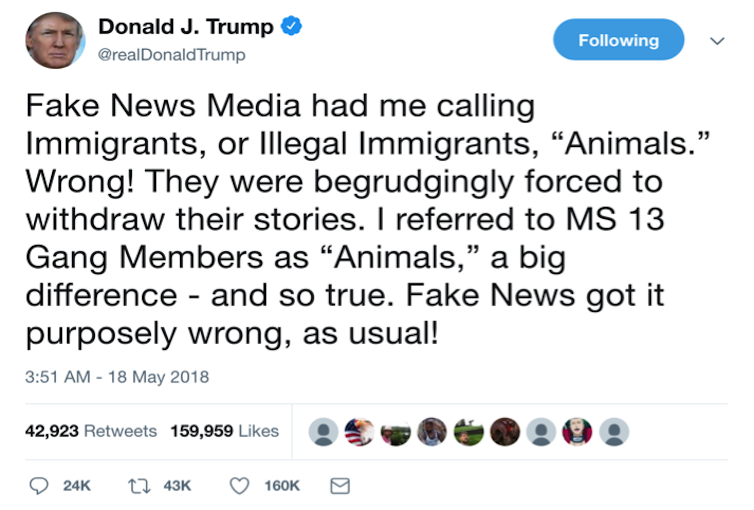

Trump is particularly fond of horrific descriptions of acts committed by the MS-13 gang. By giving graphic details of their killings, exaggerating their numbers, remaining vague about their origins, and conflating them with undocumented immigrants, Donald Trump makes the dehumanisation of all immigrants acceptable by a large segment of the population.

He calls them an “infestation” and “animals” that are “preying on children”.

If the viciousness of MS-13 is a reality, it is also noted, according to a New York Times article, that “MS-13 members make up less than 1% of the gang members in the United States”, “their numbers are stagnant” and more generally “few immigrants commit violent crimes”.

President Trump has also repeatedly used black radical singer Oscar Brown Jr.’s song “The Snake” to illustrate the supposedly evil nature of immigrants. It refers to a snake, freezing in the cold, who persuades a woman to take him into her house and then ends up biting her.

Trump uses this allegory to suggest that immigrants – and not just undocumented ones – will end up hurting their host country because they are like a “reptile with a grin”.

This constant amalgam allows the president to deny any charge of anti-immigrant racism and play the victim of the “fake-news media”:

Victimization

Settlers escaping the Dakota War of 1862, when Dakota tribes systematically attacked German farms in an effort to drive out the settlers. Such events fuelled the ‘white victim’ narrative. Wikimedia

In the promotion and acceptance of immoral policies, dehumanization is an important but insufficient step. It also requires victimization, or “victimage”, to use Kenneth Burke’s term.

In the heroic tale of the frontier, the victimisation of the white settlers served to alleviate any guilt that might have existed regarding the treatment of the natives. This process has been very clearly been at play with Donald Trump.

Just two days after signing an executive order that would hold families of immigrants together instead of separating them, Trump held a meeting for the American families of victims killed by illegal immigrants. Their victimisation was necessarily greater: not only were they permanently separated from their loved ones, Trump insisted, but they also victims of the media, which he asserted did not report on their tragedy:

By pitting the grief of one family against that of another, Trump downplayed the tragedy of the immigrant children and toddlers forcibly separated their parents. At the same time, his victimage rhetoric offers redemption by relieving his supporters of any guilt they might possibly feel for the mistreatment of immigrants, which may explain why his policy remains popular for a majority of Republicans.

This analysis highlights the cruel irony of this racialised vision: the brown skin of these immigrants from Central America is the visible sign that they belong to the same indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Trump’s attitude toward contemporary migrants also reveals his contempt for history when he is seen “honouring” Native American tribes in front of a painting of president Andrew Jackson, who was known as an “Indian killer”, or when Trump’s administration proposes to classify Native Americans as a race.

Their treatment today – and those of immigrants – echoes that of their cousins in the past, including the trauma of family separation. They too were denied the right to move freely in a continent their ancestors had settled long before the white man, and certainly long before Donald Trump’s grandparents emigrated to America.

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate