The U.S. is in multiple international trade wars. After President Trump ordered higher taxes on some Chinese imports, the Chinese retaliated. The trade dispute now involves as much as US$200 billion worth of Chinese-made goods. Trump has also targeted the European Union, Canada and Mexico with tariffs. Most economists disagree with this approach, and nearly all predict the trade wars will raise prices for American consumers on a wide array of products.

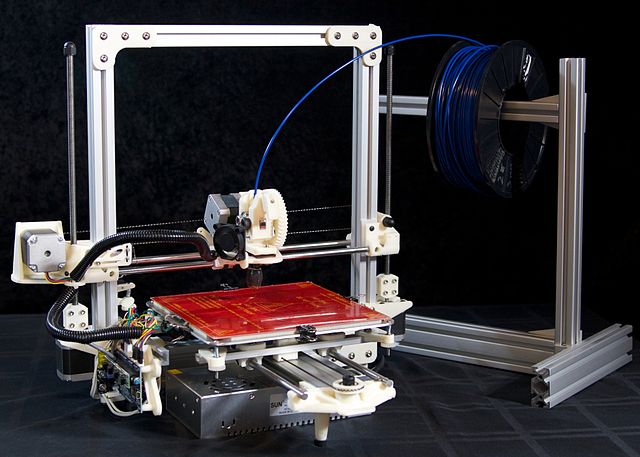

As an expert in distributed digital manufacturing, I see clearly that one industry stands to gain significantly as these economic conflicts escalate: 3D printing, the process of using digital blueprints to make real physical objects by precisely adding material one thin layer a time. High-end manufacturers have adopted 3D printing as the technology has matured, but there are also low-cost systems consumers can use to save money as prices of everyday purchases climb.

Significant savings

Stroll through any aisle at Walmart and you will notice that a lot of what you can purchase comes from China and is made from plastic, because it simply costs significantly less due to China’s expertise in manufacturing.

The shelves of many retail stores are packed with cheap plastic items. Rylie Kostreva, Michigan Tech, CC BY-SA

Even five years ago, using a 3D printer to create products at home could beat the costs of Chinese-manufactured products by 90 percent or more. A recent study I co-authored found that even inexperienced consumers could make their money back from investing in a $1,250 3D printer within six months. By printing just one product a week over the course of five years, a consumer could not only recoup all the costs associated with buying and running the printer: They would save more than $12,000. These savings only increase as trade wars raise prices higher.

A sharing and supportive community

For those new to 3D printing at home, there is a strong culture of sharing, where people with design skills share the digital instructions needed to print their creations on free online databases like MyMiniFactory, Thingiverse and Youmagine. There are millions of free designs already available, including jewelry, artwork, musical instruments, household items and tools.

After purchasing a plug-and-play 3D printer – for between $200 and $1,000 – consumers can use a 3D design search engine like Yeggi to scour dozens of databases for free designs, download the design files, open them and click “Print.” Most consumer items have many variations available. For example, instead of buying a drone at a store, a person could download and print one of the more than 1,900 free quadcopter designs available online. Using a 3D printer in this way is the same as using an office paper printer, although you do need to assemble more complex products like drones and scientific tools.

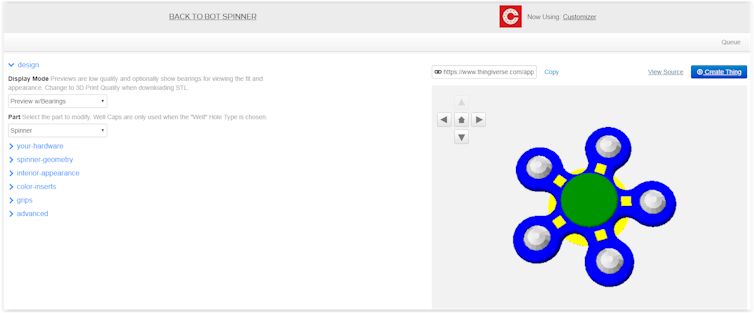

With a 3D printer, people can customize their own devices, including sizes, shapes and colors. B-O-T/Thingiverse, CC BY-SA

It gets better: Many designers let users create new custom variations of basic templates by adjusting a few parameters with free software. Freely customizable products include orthotics and artificial breast prosthetics that normally cost hundreds of dollars and can be printed for pennies, as well as toys like fidget spinners. Even simple mass-manufactured products like flexible o-rings and cheap toys like action figures, 3D puzzles and masks can be printed for far less than purchasing them from China.

With customizer software and free parametric designs, users can control almost everything about what an item looks like. B-O-T/Thingiverse, CC BY-SA

Consumers can 3D-print more valuable products for a lower cost than what is available commercially in part because 3D printing cuts out transportation, packaging and advertising costs along with markups from middlemen along the supply chain.

Changing manufacturing

The availability of 3D printers isn’t just giving consumers new options to make final products. It is already showing hints of changing global commerce as profoundly as the current trade wars might.

In fact, many companies that make 3D printers use them to make their own products. Aleph Objects, the small American manufacturer of the Lulzbot printer we used in our studies, actually uses 140 of its own printers to manufacture the 3D printers it sells. There are dozens of companies selling relatively low-cost open-source 3D printers that can make their own replacement parts. Even the latest generation of printers from HP has 3D printed parts.

The opportunities go well beyond plastics. Harley-Davidson, which is moving production outside of the U.S. to avoid retaliatory EU tariffs, uses 3D printers to prototype its motorcycles. With low-cost metal 3D printers following the footsteps of plastic 3D printers, the range of products – including many motorcycle parts – available for DIY manufacturing is set to explode. “Onshoring production” may actually mean 3D printing the products you want in your living room or garage.

And for home consumers concerned that the original China tariff list – much less its expanded replacement – includes extruders that make the plastic filaments most 3D printers use as raw materials, there’s a new solution. My research group just freely released the design of a recyclebot that makes 3D printing filament from post-consumer plastic waste. The device itself is made of mostly 3D printable parts and drops the cost of filament from commercial prices of around $10 to $20 per pound to only a few pennies per pound to make it at home. China can never compete with that – even without tariffs.

In the end, Trump may be right: The trade war may drive manufacturing back to the United States – just not in the way he predicted.

Professor Joshua M. Pearce receives funding from the Air Force Research Laboratory (ARFL) through America Makes: The National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute, which is managed and operated by the National Center for Defense Manufacturing and Machining (NCDMM). He also receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), and the National Science Foundation (NSF) for 3D printing related projects. In addition, his past and present research is supported by many non-profits and for-profit companies in the open source additive manufacturing industry including re:3D, 3D4Edu, Miller, Aleph Objects, CNC Router Parts, Virtual Foundry, Ultimaker and Youmagine, Cheap 3D Filaments, MyMiniFactory, Zeni Kinetic, Matter Hackers, and Ultimachine. He has no direct conflicts of interests.

Professor Joshua M. Pearce receives funding from the Air Force Research Laboratory (ARFL) through America Makes: The National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute, which is managed and operated by the National Center for Defense Manufacturing and Machining (NCDMM). He also receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), and the National Science Foundation (NSF) for 3D printing related projects. In addition, his past and present research is supported by many non-profits and for-profit companies in the open source additive manufacturing industry including re:3D, 3D4Edu, Miller, Aleph Objects, CNC Router Parts, Virtual Foundry, Ultimaker and Youmagine, Cheap 3D Filaments, MyMiniFactory, Zeni Kinetic, Matter Hackers, and Ultimachine. He has no direct conflicts of interests.

Nintendo Shares Slide After Earnings Miss Raises Switch 2 Margin Concerns

Nintendo Shares Slide After Earnings Miss Raises Switch 2 Margin Concerns  Nvidia Nears $20 Billion OpenAI Investment as AI Funding Race Intensifies

Nvidia Nears $20 Billion OpenAI Investment as AI Funding Race Intensifies  Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race

Nvidia Confirms Major OpenAI Investment Amid AI Funding Race  SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers

SoftBank and Intel Partner to Develop Next-Generation Memory Chips for AI Data Centers  SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates

SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates  Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Says AI Investment Boom Is Just Beginning as NVDA Shares Surge

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang Says AI Investment Boom Is Just Beginning as NVDA Shares Surge  AMD Shares Slide Despite Earnings Beat as Cautious Revenue Outlook Weighs on Stock

AMD Shares Slide Despite Earnings Beat as Cautious Revenue Outlook Weighs on Stock  Elon Musk’s SpaceX Acquires xAI in Historic Deal Uniting Space and Artificial Intelligence

Elon Musk’s SpaceX Acquires xAI in Historic Deal Uniting Space and Artificial Intelligence  Tencent Shares Slide After WeChat Restricts YuanBao AI Promotional Links

Tencent Shares Slide After WeChat Restricts YuanBao AI Promotional Links  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  Google Cloud and Liberty Global Forge Strategic AI Partnership to Transform European Telecom Services

Google Cloud and Liberty Global Forge Strategic AI Partnership to Transform European Telecom Services