Russian voters have been heading to the polls this week. But it would be misleading to say they were voting to choose a president. That’s already been done for them – it’ll be Vladimir Putin.

If there had ever been any doubt that the president of 24 years would be returned for another six, Russia’s supreme court removed that earlier this month when it upheld a decision of the Central Election Commission to ban anti-war candidate Boris Nadezhdin from running. Not that he was going to win – the director of independent Russian pollster the Levada Center, Lev Gudkov, estimated that Nadezhdin would have won about 4% of the vote had he been on the ballot. Another anti-war candidate, television journalist Yekaterina Duntsova, was banned from running last December.

Anyone else who might be a focus for opposition is either in jail, dead or exiled.

This year votes will reportedly be cast using a new digital system, which many fear will allow voters to be monitored. But Natasha Lindstaedt, a Russian politics specialist at the University of Essex, believes that with Putin forecast to hoover up 75% of the votes cast, the Kremlin will be more concerned at the idea that people will indicate their opposition to the Russian president by failing to vote at all.

Faced with a similar lack of opposition talent to back, Iranian voters recently stayed at home in droves. Turnout for the parliamentary election was a lacklustre 41% – the lowest for a parliamentary election since the inception of the Islamic Republic in 1979. Lindstaedt says the Kremlin has spent a reported €1 billion (£850 million) on propaganda in the lead up to the poll. It’s also important for Putin to reinforce the image of his legitimacy in case he needs to call on more Russians to fight.

If you want to read more about this week’s election, Adam Lenton – a Russia expert at Wake Forest University in North Carolina – offers this analysis which identifies three key issues to look out for.

If you are thinking that Putin will never relinquish his grip on power, you are probably right. Robert Person, a professor of international relations at the United States Military Academy West Point, says Putin’s got every reason to want to die in office – not least because any successor would likely want him out of the way. So, as Person writes here, there’s no succession plan and no public figures who – for the present at least – appear capable of mustering sufficient support to effect a seamless transfer of power.

Were Putin to die tomorrow, he’d be succeeded by the prime minister, Mikhail Mishustin. But Mishustin is a virtual nonentity, a former tax official with no base of his own and a trust rating of just 18%. It’s hard to see him having the momentum to take the reins on a permanent basis.

One opposition group that is making its voice heard is made up of wives of Russian troops fighting in Ukraine. Previously, write Jennifer Mathers and Natasha Danilova, it had been soldiers’ mothers who were very vocal in their opposition to the war in Chechnya in the 1990s. This time round it’s the wives of men who are serving, reflecting perhaps the relatively older age profile of combatants in Ukraine. Many soldiers are in their 30s and 40s, rather than their late teens and early 20s, as in Chechnya.

Mathers and Danilova, experts in international relations at the universities of Aberystwyth and Aberdeen respectively, say the women have gradually increased the public pressure on the Kremlin as the conflict has moved into a third year, moving from largely online opposition to regular protests. Rather than set themselves against the war in itself, they are focusing on securing concessions such as more regular leave for their loved ones.

But, Mathers and Danilova note, there are signs that the Kremlin is beginning to up the pressure on these women, visiting their homes and mounting increasingly strident media attacks on their group.

British boots on the ground?

Red faces among Germany’s political and military leadership recently when it emerged that an unencrypted phone call between senior Luftwaffe officers had revealed that British troops are in Ukraine helping with the deployment and targeting of Storm Shadow cruise missiles. The call had been intercepted and passed to Russian state broadcaster RT.

The Kremlin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, said the call was “proof” that the west was orchestrating the war against Russia. Closer to home, one question being asked was whether this makes the UK a co-combatant.

Christoph Bluth, professor of international relations at the University of Bradford, examines the international law involved and finds that under principles established since the second world war, helping Ukraine in this limited way does not violate the UK’s neutrality. But Moscow will no doubt use it as a political opportunity to escalate its anti-Nato rhetoric, Bluth writes.

Memory and culture

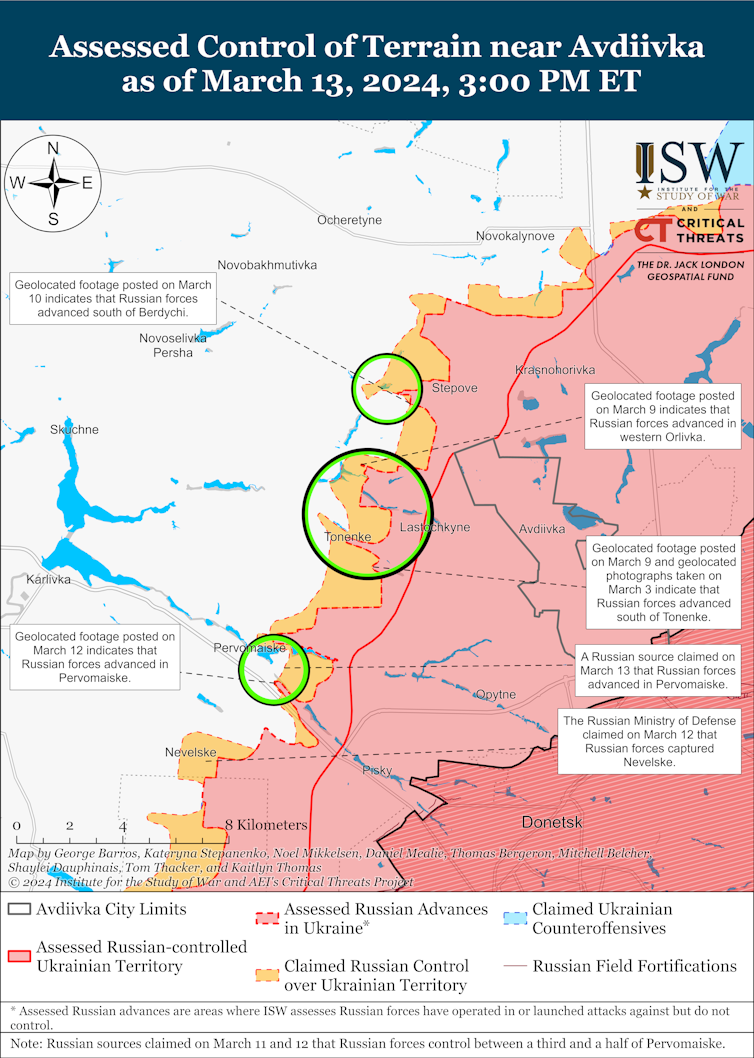

There was some heartening news from Washington this week when it was revealed that Joe Biden had managed to scrape together US$300 million (£235 million) to supply the Ukraine military with at least some ammunition as it struggles to hold the line against better-supplied Russian forces. But the west’s slow response to pleas from the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, for more military aid remains a huge concern. As the map below shows, Russia continues to make gains west of the town of Avdiivka, which they captured in mid-February.

Russia continues to make gains west of the town of Avdiivka, which they captured in mid-February. Institute for the Study of War

Gervase Phillips, a historian at Manchester Metropolitan University, see parallels with the Polish uprising in November 1830. Initially, support for the Polish people against the oppressive rule of the autocratic Tsar Nicolas I was widespread, and early success on the battlefield made this seem a worthy cause in liberal salons across Europe.

But, Phillips writes, this was not to last. The Poles’ European allies failed to back their intentions with military aid, and the uprising developed into a war of attrition in 1831. Eventually Russian troops fought their way to Warsaw and the uprising failed. Will Ukraine suffer the same fate?

Pope Francis I certainly appears to think so. The Holy Father sparked outrage in Kyiv (and elsewhere) last weekend when in an interview with Swiss public broadcaster RSI, he said Ukraine should find the “the courage to raise the white flag”. “When you see that you are defeated … you need to have the courage to negotiate,” he added. This drew an immediate and caustic response from Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba: “Our flag is a yellow and blue one,” he said, adding: “This is the flag by which we live, die, and prevail. We shall never raise any other flags.”

Tim Luckhurst, a former BBC journalist now researching second world war newspaper history at the University of Durham, was reminded of the way Pope Pius XII failed to openly criticise Nazi Germany during the worst excesses of the Holocaust, preferring instead to safeguard the rights of German Catholics. Meanwhile round-ups of Italian Jews took place within sight of the Vatican.

Meanwhile, as admirers of the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny gathered in Moscow for his funeral, the biggest festival of documentary film in the former Soviet countries opened in Latvia with a minute’s silence. Artdocfest was first held in Moscow in 2007 and showcased some of the best Russian and foreign-language documentaries. After Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, the Kremlin began to pressure its organisers and withdrew all state support. In March 2022, after Putin launched his invasion, the festival relocated permanently to Riga.

Jeremy Hicks, professor of Russian culture and film at Queen Mary University of London, gives us a taste of the best films being showcased at the festival.

Podcast: Putin’s conspiracy theories

Aptly enough, the subject of our podcast The Conversation Weekly is how Putin has managed to exert such a firm grip on power in Russia. Host Gemma Ware talks with Ilya Yablokov, a specialist in disinformation at the University of Sheffield.

Yabolokov, who has written regularly for us on the Russian media, has been researching the way Russia’s conspiracy culture has become a key tool for Putin’s regime: “Conspiracy theories are one of the few ways of keeping the society together and to prevent the change of the regime,” he says.

Incidentally, one of those theories is that shadowy western agencies orchestrated Navalny’s death to make Putin look bad. True or not, that mission has been well and truly accomplished.

Middle East Conflict Escalates After Khamenei’s Death as U.S., Israel and Iran Exchange Strikes

Middle East Conflict Escalates After Khamenei’s Death as U.S., Israel and Iran Exchange Strikes  BTC Blasts +$3,500 to $66,300 High — ETF Inflows Spark Institutional Comeback, Bulls Target $75K

BTC Blasts +$3,500 to $66,300 High — ETF Inflows Spark Institutional Comeback, Bulls Target $75K  Trump to Attend White House Correspondents’ Dinner 2026, Ending Long Boycott

Trump to Attend White House Correspondents’ Dinner 2026, Ending Long Boycott  The strikes on Iran show why quitting oil is more important than ever

The strikes on Iran show why quitting oil is more important than ever  Argentina Tax Reform 2026: President Javier Milei Pushes Lower Taxes and Structural Changes

Argentina Tax Reform 2026: President Javier Milei Pushes Lower Taxes and Structural Changes  Australia Rules Out Military Involvement in Iran Conflict as Middle East Tensions Escalate

Australia Rules Out Military Involvement in Iran Conflict as Middle East Tensions Escalate  AI is already creeping into election campaigns. NZ’s rules aren’t ready

AI is already creeping into election campaigns. NZ’s rules aren’t ready  Trump Says U.S. Combat Operations in Iran Will Continue Until Objectives Are Met

Trump Says U.S. Combat Operations in Iran Will Continue Until Objectives Are Met  Marco Rubio to Brief Congress After U.S.-Israeli Strikes on Iran

Marco Rubio to Brief Congress After U.S.-Israeli Strikes on Iran  Does international law still matter? The strike on the girls’ school in Iran shows why we need it

Does international law still matter? The strike on the girls’ school in Iran shows why we need it  Zelenskiy Urges Change in Iran After U.S. and Israeli Strikes, Cites Drone Support for Russia

Zelenskiy Urges Change in Iran After U.S. and Israeli Strikes, Cites Drone Support for Russia  Pentagon Downplays ‘Endless War’ Fears After U.S. Strikes on Iran Escalate Conflict

Pentagon Downplays ‘Endless War’ Fears After U.S. Strikes on Iran Escalate Conflict  Trump Launches Operation Epic Fury: U.S. Strikes on Iran Mark High-Risk Shift in Middle East

Trump Launches Operation Epic Fury: U.S. Strikes on Iran Mark High-Risk Shift in Middle East