Many women took to the streets worldwide on September 28, the global day of action for safe abortion successes and put forth new demands for women’s right to access safe, free and legal abortion.

Right to access safe abortion is under threat in many countries, from the United States to Poland, from Argentina to Ireland where women are still fighting for it. Religion, specifically Catholicism, has often been stated as the main obstacle to birth control and abortions. As such, many Catholic majority countries have strict abortion laws. Most remarkably among those, Andorra, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Malta, Nicaragua and Vatican come to fore with complete abortion bans.

But what about Muslim-dominant countries?

Nearly 80% of women in the Middle East and North Africa live in countries where abortion laws are restricted. Among those, 55% live in countries where abortion is prohibited except to save the mother’s life and 24% live in countries where abortion is permitted only to preserve women’s physical or mental health. Today, only Turkey and Tunisia allow elective abortions (abortion on demand). Although, there are no countries in the region with complete abortion bans, abortion restrictions narrow the grounds for women’s access to safe abortion.

Just like elsewhere, abortion appears to be a highly controversial topic for the Muslim-majority countries, as well as for the Islamic jurisprudence. Even in countries where it is legal, as in Turkey, abortion regime is constantly challenged and attacked by opposing political and religious discourses. Similarly, in Tunisia, despite the legal framework, women still report being judged by the medical personnel and society for obtaining abortion.

What does Islam say about abortion?

In general, Muslim authorities consider abortion as an act of interfering the role of Allah (God), the only author of life and death. However, different Islamic schools have different views on abortion. According to the Hanafi School, which is predominant in the Middle East, Turkey and central Asia, and that constituted the main body of law during the Ottoman Empire, abortion was conceptualized as ıskât-ı cenîn, which can be translated as the expulsion of the fetus.

At the outset, this terminology was obscure as it made no distinction between miscarriage and abortion. Moreover, within the Hanafi school, it was argued that ıskât-ı cenîn is mekrouh, meaning unwanted rather than haram (prohibited), before the fetus is 120 days old, given that the fetus would not be ensouled until then. Yet, even if it is mekrouh, termination of pregnancy was entrenched to husband’s approval and it did not constitute a right or decision on women’s part.

At the same time, other Islamic schools have diverging opinions on abortion. Shafi school, which is dominant in Southeast Asia and parts of Africa, majorly permits termination of pregnancies up to 40 days and opinions diverge within the school as per the foetal development advances.

Some Shafi imams even tolerated abortion up to 120 days. Although the Hanbali school that is dominant in Saudi Arabia and United Arabic Emirates does not have a unified stance on abortion, some opinions permit abortion until the 120 days. Finally, the Mailiki school, dominant in North Africa, affirms intermediate status of fetus as the potential of life and prohibits abortion entirely. As a matter of fact, all Islamic schools consider fetus to be ensouled by 120 days of conception and none of them permit abortion after this stage.

New socio-political concerns

In many Muslim-majority countries, Islamic jurisprudence influenced abortion legislations. However, as new socio-political concerns emerged across time, abortion legislations have been reformed. In the case of the Ottoman Empire, the relative “free medium” offered by the Hanafi school was challenged by a new pro-natalist and modernist agenda emerged toward the late eighteenth-century. As the empire was moving toward decline, modernization and population growth was seen as a remedy to ensure military, economic, and political stability. Inspired by Europe, Ottomans aimed to achieve a breakthrough via a vast reformation and codification process.

Childbirth as portrayed in Zenanname (Book of Women) by Enderunlu Fazıl, published in 1253-1286 [1837-1869].

In 1858, the Imperial Ottoman Penal Code – modelled after the French Penal Code of 1810 (Code Pénal 1810)– was adopted. The new Penal Code officially prohibited and criminalized abortion through a unique harmonization of the French Penal Code with the Islamic jurisprudence. Henceforth, abortion was declared haram (prohibited) legally across all Ottoman territories. Nonetheless, in the Ottoman jurisprudence, abortion was conceptualized exclusively as a social phenomenon. The recorded prosecutions which followed the implementation of the Penal Code illustrate this point, as they criminalize abortion practitioners, as in doctors, nurses, pharmacists, etc., rather than women themselves.

Following the Ottoman jurisprudence, many ex-Ottoman territories kept up with abortion restrictions. However, when we look at Muslim-majority countries, we also witness a diversity in abortion laws as they allow and prohibit abortion on different grounds. Today in many of those countries, abortion is often only allowed when women’s life is under danger, when the fetus is malformed or when the pregnancy is a result of a criminal act, such as a rape. Though these grounds allow some women to obtain abortion, they still reinforce medical supervision and legal proceeding, leaving no room for elective abortions.

Restricting abortion drives it underground

It is widely and scientifically known that restricting abortion does not efface the practice. On the contrary, it drives abortions underground and gives birth to clandestine and unsafe abortions, as well as maternal mortality. As women use dangerous methods to terminate their unwanted pregnancies, they risk their health, fertility and even lives. Every year, 47,000 women die from complications related to unsafe abortion. Middle East and North Africa, following Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, looms large as the third region with severe maternal mortality rates.

Moreover, abortion restrictions hit women from lower economic background the most. Often women who can afford might find the possibility to travel to access safe abortion elsewhere. Some women also manage to negotiate with local medical staff to receive service. For some others, the black market is the only resort. Many women become victims of scammers who sell fake abortion pills at high costs. Even in cases where women manage to access to reliable services or medicines, they seldomly access to reliable information and relevant care. This leads to isolation in their abortion experience, as well as increased pain.

Wind of change on apps

Nevertheless, with the advent of medical abortion and telemedicine abortion, safe abortion alternatives flourish despite legal restrictions. Many women living in the Muslim-majority countries, or elsewhere with restrictive abortion laws, consult to online telemedicine services to receive help and information on the self-administration of medical abortion pills.

Studies have proven that self-administration of medical abortion pills obtained through telemedicine services is safe and effective in early pregnancies.

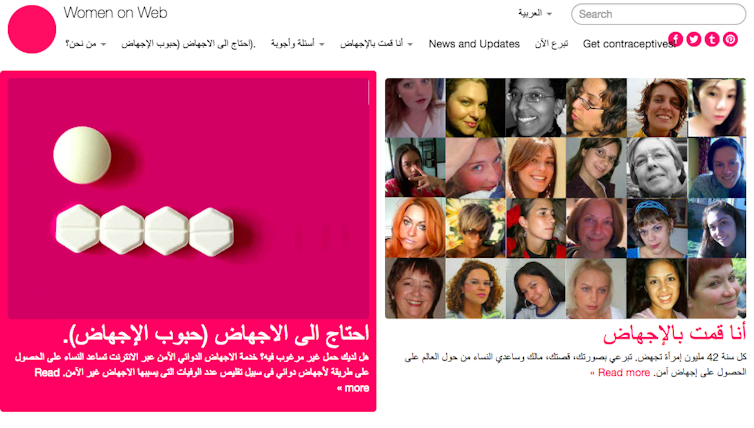

Being one of such telemedicine services providing safe abortion in restrictive settings, Women on Web (WoW), helps around 60,000 women every year. Their website is available in 16 languages, including Arabic, Persian and Turkish.

Interface of Women on Web website in Arabic. Women on Web is a telemedicine abortion service providing help and information to women living in restrictive settings.

However, in some countries like Saudi Arabia and Turkey, Women on Web website is banned. In this case, to circumvent the censure, women use an app on their smart phones to ask for help.

Today abortion appears to be haram, illegal and clandestine in large parts of the Muslim world. Despite this, women continue to challenge the status quo and archaic laws through their daily practices and activism.

In 2012, in response to a planned legislation to restrict abortion in Turkey, thousands of women organized a pro-choice rally in Istanbul. Taking streets to claim their right to safe abortion, women claimed for their bodily autonomy: “Abortion is a right, decision belongs to women” (Kürtaj haktır, karar kadınların).

Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links

Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links  Court Allows Expert Testimony Linking Johnson & Johnson Talc Products to Ovarian Cancer

Court Allows Expert Testimony Linking Johnson & Johnson Talc Products to Ovarian Cancer  Panama Supreme Court Voids CK Hutchison Port Concessions, Raising Geopolitical and Trade Concerns

Panama Supreme Court Voids CK Hutchison Port Concessions, Raising Geopolitical and Trade Concerns  Supreme Court Signals Skepticism Toward Hawaii Handgun Carry Law

Supreme Court Signals Skepticism Toward Hawaii Handgun Carry Law  U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday

U.S. Lawmakers to Review Unredacted Jeffrey Epstein DOJ Files Starting Monday  CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences

CK Hutchison Launches Arbitration After Panama Court Revokes Canal Port Licences  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  Minnesota Judge Rejects Bid to Halt Trump Immigration Enforcement in Minneapolis

Minnesota Judge Rejects Bid to Halt Trump Immigration Enforcement in Minneapolis  US Judge Rejects $2.36B Penalty Bid Against Google in Privacy Data Case

US Judge Rejects $2.36B Penalty Bid Against Google in Privacy Data Case