It’s been more than a year since the UK economy was thrown into crisis after then-prime minister Liz Truss suggested making a wealth of unfunded tax cuts in her September 2022 mini-budget. But a recent bond market sell-off has now sent borrowing costs rocketing again, pushing the bond market even higher than after Truss’s announcement.

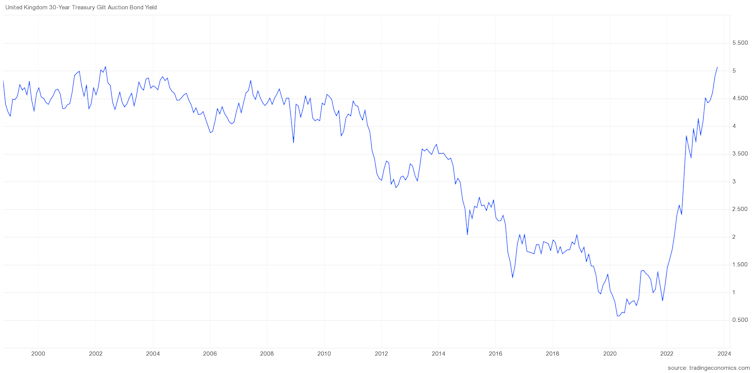

Yields on UK treasury bonds – the rate the UK government must pay to borrow money – have risen to approximately 4.6% for ten-year bonds. Yields on 30-year bonds hit 5.1%, the highest since 1998.

Banks also use this rate as a key benchmark to set commercial loan rates, so this means borrowing costs are rising for businesses, as well as for the government. Two-year and five-year treasury yields (which are used to set mortgage rates) are also above the budget-fuelled high of last year, and at levels not seen in over ten years.

UK bond yields (30 year), 1998-2023:

The government issues treasury bonds at a particular interest rate that corresponds to a fixed value. Investors buy the bonds and the government uses the money to finance its spending. Since it’s a loan, the government repays the investors but also pays interest on the bond until repayment – this is the yield.

For example, a 5% bond issued for a £100 earns the investor £5 interest. If the government issues a later bond at 6% for £100 (£6 interest), the 5% (£5) bond’s value drops. This is why when bond prices fall, the yield rises and vice versa.

Right now, UK treasury yields are rising because investors are trying to sell UK government bonds – falling demand makes the price drop.

And this isn’t just happening in the UK. The same is true around the world. US bonds, for example, recently hit a 16-year high.

Why is this happening right now?

This is a tale of two central banks navigating difficult economic conditions. In September, both the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve chose not to increase their main interest rates (which are at 5.25% and 5.5% respectively). The reasons for these decisions and the position of each economy are driving the bond market changes.

In terms of the economy, headline inflation is currently 6.7% (6.2% for core, which strips out more volatile items like energy) in the UK, and 3.7% (4.3% core) in the US. GDP growth is at 0.6% for the UK and 2.4% for US. So, the two economies are on different tracks.

These figures influence financial market expectations about what central banks might do next with interest rates. The divergence in growth rates and inflation between the two economies had signalled that the banks would take different routes at their September meetings.

Prior to the latest decision by the Bank of England, there was a general view that UK rates would rise to 5.5%, but a lower-than-expected inflation rate was announced days before the bank met to decide on rates and this led them to hold rates instead. After the meeting, the Bank of England also indicated that, while it expected its rate to remain at 5.25% for some time, it did not foresee a further rise.

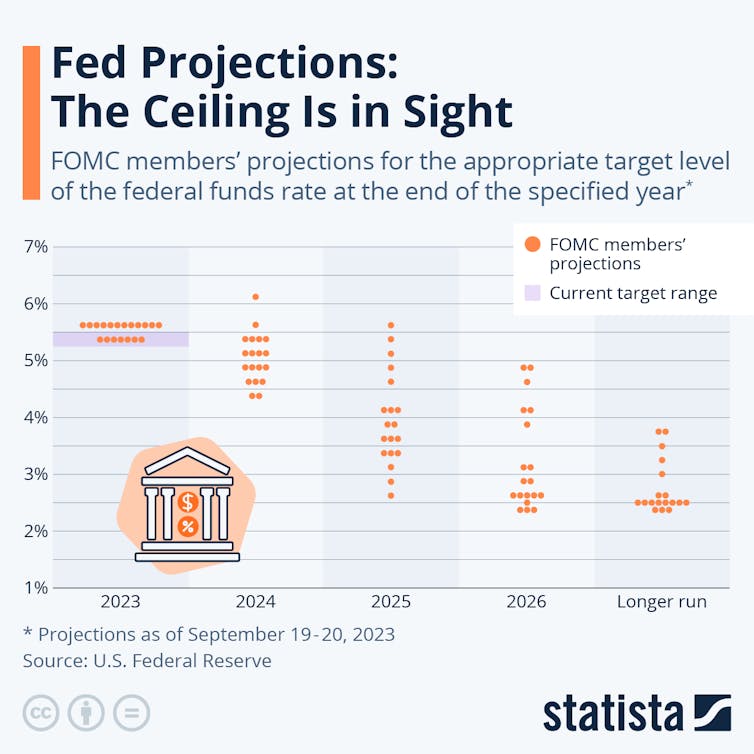

In contract, while the Federal Reserve also held rates in September, this was seen as a pause and not a stop. US rates are widely expected to rise again this year.

Twelve members of the Fed’s 19-person rate-setting committee expect one more 0.25% interest rate hike this year, while 7 FOMC members expect no change before the end of the year. Statista, CC BY-ND

What has this got to do with bond yields?

The expected rise in US rates means investors do not want to hold US bonds whose value will fall as a result. As explained before, when newer bonds are issued at higher yields (to reflect the bank’s most recent interest rate decison), existing bonds (those previously issued with lower yields) will be valued less by investors because they will get less in interest payments for holding them.

This is why investors are selling US bonds. For a related, but slightly different reason, investors also don’t want to hold UK bonds. As US bonds will soon earn a higher yield, investors are selling UK bonds to reposition their portfolios towards the US, where they will be able to earn a higher yield.

This also has implications for the value of the pound. Since the Bank of England’s decision not to raise the interest rate in September, the value of the pound has fallen versus the US dollar. This is because the same investors that are selling UK Treasuries and driving up yields, are also selling pounds to buy US dollars.

The UK is not alone in feeling this effect, the euro is also weakening and against the US dollar, while the Japanese yen is close to the same low that prompted an intervention by the Bank of Japan around this time last year.

Global currency markets. Dilok Klaisataporn/Shutterstock

In each case, the reason is the same: the strength of the US economy relative to other economies (0.5% GDP growth for the Eurozone and 1.6% for Japan) is attracting more investors. As with the UK, the policy rates for the Eurozone and Japan are below those of the US, with each central bank indicating an intention not to make further increases.

But both of these effects – higher treasury yields and a depreciating pound – spell bad news for the UK economy.

The higher yields imply higher borrowing costs, including interest payments for the government, as well as both mortgages and business loans. The fall in the value of the pound means that imports are more expensive. Together with the fact that many commodities (such as oil) are priced in US dollars, this can contribute to higher inflation.

Since the economy is also barely growing, both issues will continue to have a dampening effect on the UK.

David McMillan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Australian Household Spending Dips in December as RBA Tightens Policy

Australian Household Spending Dips in December as RBA Tightens Policy  U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains

U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains  Asian Markets Surge as Japan Election, Fed Rate Cut Bets, and Tech Rally Lift Global Sentiment

Asian Markets Surge as Japan Election, Fed Rate Cut Bets, and Tech Rally Lift Global Sentiment  Asian Stocks Slip as Tech Rout Deepens, Japan Steadies Ahead of Election

Asian Stocks Slip as Tech Rout Deepens, Japan Steadies Ahead of Election  Vietnam’s Trade Surplus With US Jumps as Exports Surge and China Imports Hit Record

Vietnam’s Trade Surplus With US Jumps as Exports Surge and China Imports Hit Record  U.S. Stock Futures Rise as Markets Brace for Jobs and Inflation Data

U.S. Stock Futures Rise as Markets Brace for Jobs and Inflation Data  Yen Slides as Japan Election Boosts Fiscal Stimulus Expectations

Yen Slides as Japan Election Boosts Fiscal Stimulus Expectations  UK Starting Salaries See Strongest Growth in 18 Months as Hiring Sentiment Improves

UK Starting Salaries See Strongest Growth in 18 Months as Hiring Sentiment Improves  South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom

South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom  Oil Prices Slip as U.S.-Iran Talks Ease Middle East Tensions

Oil Prices Slip as U.S.-Iran Talks Ease Middle East Tensions  Nikkei 225 Hits Record High Above 56,000 After Japan Election Boosts Market Confidence

Nikkei 225 Hits Record High Above 56,000 After Japan Election Boosts Market Confidence  China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices

China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices  Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns

Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns  Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran

Trump Signs Executive Order Threatening 25% Tariffs on Countries Trading With Iran  Australian Pension Funds Boost Currency Hedging as Aussie Dollar Strengthens

Australian Pension Funds Boost Currency Hedging as Aussie Dollar Strengthens  Japan Economy Poised for Q4 2025 Growth as Investment and Consumption Hold Firm

Japan Economy Poised for Q4 2025 Growth as Investment and Consumption Hold Firm