If you’ve ever observed a river rushing down a mountain or played in the waves at the beach, you’ve felt that moving water contains a lot of energy. A river can push you and your kayak downstream, sometimes very quickly, and waves crashing into you at the beach can knock you back, or even knock you over.

There is a long history of harnessing the energy in the flowing waters of rivers to do useful work. For centuries, people used water power to grind grain to make flour and meal. In modern times, people use water power to generate clean electricity to help power buildings, factories and even cars.

Energy in flowing waters

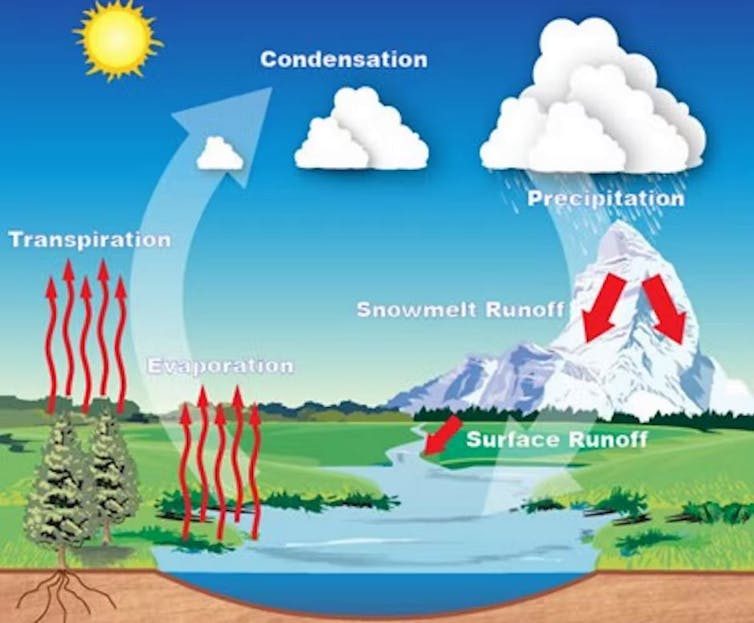

The energy in these moving waters comes from gravity. As part of the Earth’s water cycle, water evaporates from the Earth’s surface or is released from plants. When the released water vapor is carried to cooler, higher altitudes like mountainous regions, it condenses into cloud droplets. When these cloud droplets become big enough, they fall from the sky as precipitation, either as a liquid (rain) or, if it is cold enough, as a solid (snow). Over land, precipitation tends to fall on high altitude areas at first.

The water cycle. National Weather Service

The pull of gravity causes the water to flow. If the water falls as rain, some of it flows downhill into natural channels and becomes rivers. If the water falls as snow, it will slowly melt into water as temperatures warm and follow the same paths. The rivers that form consist of water from precipitation starting at high altitudes and flowing down the steep slopes of mountains.

Converting flowing water to electricity

Hydropower facilities capture the energy in flowing water by using a device called a turbine. As water runs over the blades of a turbine – kind of like a giant pinwheel – they spin. This spinning turbine is connected to a shaft that spins inside a device called a generator, which uses an effect called induction to convert energy in the spinning shaft to electricity.

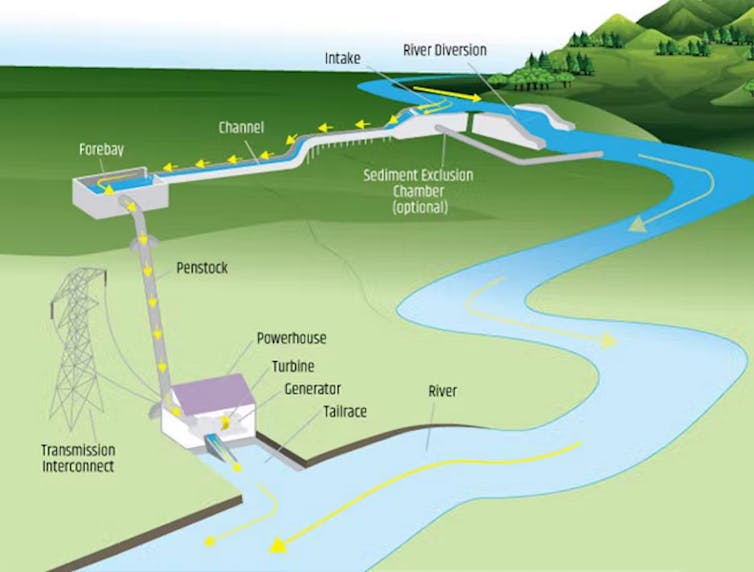

There are two main kinds of hydropower facilities. The first kind is called a “run-of-the-river” hydropower facility. These facilities consist of a channel to divert water flow from a river to a turbine. The electricity production from the turbine follows the timing of the river flow. When a river is running full with lots of spring meltwater, it means the turbine can produce more electricity. Later in the summer, when the river flow decreases, so does the turbine’s electricity production. These facilities are typically small and simple to construct, but there is limited ability to control their output.

A run-of-the-river hydropower facility. U.S. Department of Energy

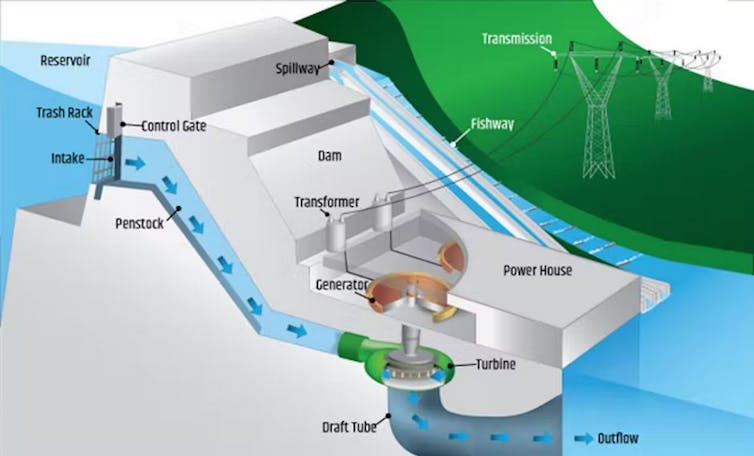

The second kind is called a “reservoir” or “dam” hydropower facility. These facilities use a dam to hold back the flow of a river and create an artificial lake behind the dam. Hydropower dams have intakes that control how much water flows through passages inside the dam. Turbines at the bottom of these passages convert the flowing water into electricity.

To produce electricity, the dam operator releases water from the artificial lake. This water speeds up as it falls down from the intakes near the top of the dam to the turbines near the bottom. The water that exits the turbines is released back into the river downstream. These reservoir hydropower facilities are usually large and can affect river habitats, but they can also produce a lot of electricity in a controllable manner.

A dam-based hydropower facility. U.S. Department of Energy

The future of hydropower

Hydropower depends on the availability of water in flowing rivers. As climate change affects the water cycle, some regions may have less precipitation and consequently less hydropower generation.

Also, making electricity isn’t the only thing dam operators have to think about when they decide how much water to let through. They have to make sure to keep some water behind the dam for people to use and let enough water through to preserve the river habitat below the dam.

Hydropower can also play a role in limiting climate change because it is a form of renewable electricity. Hydropower facilities can increase and decrease their electricity production to fill in gaps in wind and solar generation.

Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies

Missouri Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Challenging Starbucks’ Diversity and Inclusion Policies  Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users

Instagram Outage Disrupts Thousands of U.S. Users  Hims & Hers Halts Compounded Semaglutide Pill After FDA Warning

Hims & Hers Halts Compounded Semaglutide Pill After FDA Warning  Washington Post Publisher Will Lewis Steps Down After Layoffs

Washington Post Publisher Will Lewis Steps Down After Layoffs  TrumpRx Website Launches to Offer Discounted Prescription Drugs for Cash-Paying Americans

TrumpRx Website Launches to Offer Discounted Prescription Drugs for Cash-Paying Americans  Baidu Approves $5 Billion Share Buyback and Plans First-Ever Dividend in 2026

Baidu Approves $5 Billion Share Buyback and Plans First-Ever Dividend in 2026  SoftBank Shares Slide After Arm Earnings Miss Fuels Tech Stock Sell-Off

SoftBank Shares Slide After Arm Earnings Miss Fuels Tech Stock Sell-Off  Weight-Loss Drug Ads Take Over the Super Bowl as Pharma Embraces Direct-to-Consumer Marketing

Weight-Loss Drug Ads Take Over the Super Bowl as Pharma Embraces Direct-to-Consumer Marketing  Nvidia, ByteDance, and the U.S.-China AI Chip Standoff Over H200 Exports

Nvidia, ByteDance, and the U.S.-China AI Chip Standoff Over H200 Exports  Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised

Sony Q3 Profit Jumps on Gaming and Image Sensors, Full-Year Outlook Raised  TSMC Eyes 3nm Chip Production in Japan with $17 Billion Kumamoto Investment

TSMC Eyes 3nm Chip Production in Japan with $17 Billion Kumamoto Investment  Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit

Uber Ordered to Pay $8.5 Million in Bellwether Sexual Assault Lawsuit  SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates

SpaceX Prioritizes Moon Mission Before Mars as Starship Development Accelerates  American Airlines CEO to Meet Pilots Union Amid Storm Response and Financial Concerns

American Airlines CEO to Meet Pilots Union Amid Storm Response and Financial Concerns  Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape

Trump Backs Nexstar–Tegna Merger Amid Shifting U.S. Media Landscape  Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains

Prudential Financial Reports Higher Q4 Profit on Strong Underwriting and Investment Gains  Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings