In February 1995, a small research organisation known as the SETI Institute launched what was then the most comprehensive search for an answer to a centuries-old question: are we alone in the universe?

This Sunday marks the 30th anniversary of the first astronomical observations conducted for the search, named Project Phoenix. These observations were done at the Parkes Observatory on Wiradjuri country in the central west of New South Wales, Australia – home to one of the world’s largest radio telescopes.

But Project Phoenix was lucky to get off the ground.

Three years earlier, NASA had commenced an ambitious decade-long, US$100 million Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI). However, in 1993, the United States Congress cut all funding for the program because of the growing US budget deficit. Plus, SETI sceptics in Congress derided the program as a far-fetched search for “little green men”.

Fortunately, the SETI Institute secured enough private donations to revive the project – and Project Phoenix rose from the ashes.

Listening for radio signals

If there is life elsewhere, it is natural to assume it evolved over many million years on a planet orbiting a long-lived star similar to our Sun. So SETI searches usually target the nearest Sun-like stars, listening for radio signals that are either being deliberately beamed our way, or are techno-signatures radiating from another planet.

Techno-signatures are confined to a narrow range of frequencies and produced by the technologies an advanced civilisation like ours might use.

Astronomers use radio waves as they can penetrate the clouds of gas and dust in our galaxy. They can also travel over large distances without excessive power requirements.

Murriyang, CSIRO’s 64 metre radio telescope at the Parkes Observatory, has been in operation since 1961. It has made a wealth of astronomical discoveries and played a pivotal role in tracking space missions – especially the Apollo 11 moonwalk.

As the largest single-dish radio telescope in the southern hemisphere, it is also the natural facility to use for SETI targets in the southern skies.

While Project Phoenix planned to use several large telescopes around the world, these facilities were undergoing major upgrades. So it was at Parkes that the observing program started.

On February 2 1995, Murriyang pointed towards a carefully chosen star 49 light-years from Earth in the constellation of, naturally, Phoenix. This was the first observation conducted as part of the project.

The focus cabin of Murriyang, the Parkes telescope, with the Flag of Earth, much favoured by SETI researchers. CSIRO Radio Astronomy Image Archive, CC BY-NC

A logistical and technological success

Project Phoenix was led by Jill Tarter, a renowned SETI researcher who spent many long nights at Parkes overseeing observations during the 16 weeks dedicated to the search. (Jodie Foster’s character in the 1998 movie Contact was largely based on Jill.)

The Project Phoenix team brought a trailer full of computers with state-of-the-art touch screen technology to process the data.

Bogong moths caused some early interruptions to the processing. These large, nocturnal moths were attracted to light from computer screens, flying into them with enough force to change settings.

Over 16 weeks, the Project Phoenix team observed 209 stars using Murriyang at frequencies between 1,200 and 3,000 mega-hertz. They searched for both continuous and pulsing signals to maximise the chance of finding genuine signals of alien life.

Jill Tarter in the Parkes telescope control room. CSIRO Radio Astronomy Image Archive, CC BY-NC

Radio telescopes are able to detect the faint radio emissions from distant celestial objects. But they are also sensitive to radio waves produced in modern society (our own techno-signatures) by mobile phones, Bluetooth connections, aircraft radar and GPS satellites.

These kinds of local interference can mimic the kinds of signal SETI searches are looking for. So distinguishing between the two is crucial.

To do this, Project Phoenix decided to use a second radio telescope some distance away for an independent check of any signals detected. CSIRO provided access to its 22 metre Mopra radio telescope, about 200 kilometres north of Parkes, to follow up signal candidates in real time.

Over the 16 weeks, the team detected a total of 148,949 signals at Parkes – roughly 80% of which could be easily dismissed as local signals. The team checked a little over 18,000 signals at both Parkes and Mopra. Only 39 passed all tests and looked like strong SETI candidates. But on closer inspection the team identified them as coming from satellites.

AS Jill Tarter summarised in an article in 1997:

Although no evidence for an [extraterrestrial intelligence] signal was found, no mysterious or unexplained signals were left behind and the Australian deployment was a logistical and technological success.

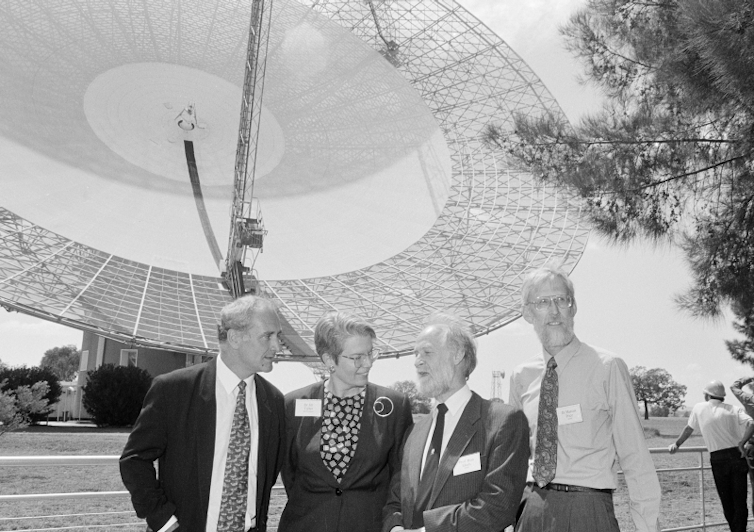

From left to right: journalist Robyn Williams, Jill Tarter, Australia Telescope National Facility Director, Ron Ekers, and Parkes Observatory Officer-in-Charge, Marcus Price, prior to the start of Project Phoenix. CSIRO Radio Astronomy Image Archive, CC BY-NC

The next generation of radio telescopes

When Project Phoenix ended in 2004, project manager Peter Backus concluded “we live in a quiet neighbourhood”.

But efforts are continuing to search for alien life with greater sensitivity, over a wider frequency range, and for more targets.

Breakthough Listen, another privately funded project, commenced in 2015, again making use of the Parkes telescope among others.

Breakthrough Listen aims to examine one million of the closest stars and 100 closest galaxies.

One unexpected signal detected at Parkes in 2019 as part of this project was examined in painstaking detail before it was concluded that it too was a locally generated signal.

The next generation of radio telescopes will provide a leap in sensitivity compared to facilities today – benefitting from greater collecting area, improved resolution and superior processing capabilities.

Examples of these next generation radio telescopes include the SKA-Low telescope, under construction in Western Australia, and the SKA-Mid telescope, being built in South Africa. They will be used to answer a wide variety of astronomical questions – including whether there is life beyond Earth.

As SETI pioneer Frank Drake once noted:

the most fascinating, interesting thing you could find in the universe is not another kind of star or galaxy … but another kind of life.

FDA Adds Fatal Risk Warning to J&J and Legend Biotech’s Carvykti Cancer Therapy

FDA Adds Fatal Risk Warning to J&J and Legend Biotech’s Carvykti Cancer Therapy  NASA Resumes Cygnus XL Cargo Docking with Space Station After Software Fix

NASA Resumes Cygnus XL Cargo Docking with Space Station After Software Fix  Trump Signs Executive Order to Boost AI Research in Childhood Cancer

Trump Signs Executive Order to Boost AI Research in Childhood Cancer  NASA Astronauts Wilmore and Williams Recover After Boeing Starliner Delay

NASA Astronauts Wilmore and Williams Recover After Boeing Starliner Delay  Neuralink Expands Brain Implant Trials with 12 Global Patients

Neuralink Expands Brain Implant Trials with 12 Global Patients  Astronomers have discovered another puzzling interstellar object − this third one is big, bright and fast

Astronomers have discovered another puzzling interstellar object − this third one is big, bright and fast  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  CDC Vaccine Review Sparks Controversy Over Thimerosal Study Citation

CDC Vaccine Review Sparks Controversy Over Thimerosal Study Citation  SpaceX Starship Test Flight Reaches New Heights but Ends in Setback

SpaceX Starship Test Flight Reaches New Heights but Ends in Setback  FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary

FxWirePro- Major Crypto levels and bias summary  SpaceX’s Starship Completes 11th Test Flight, Paving Way for Moon and Mars Missions

SpaceX’s Starship Completes 11th Test Flight, Paving Way for Moon and Mars Missions  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand