More than a month has passed since Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, the leader of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) militant group, became the de facto leader of Syria. Since then, he has dropped his nom de guerre in favour of his real name, Ahmed al-Shara, and has swapped his military attire for a suit and tie.

The change in government has led to cautious optimism among Syrians who have been celebrating the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. However, the rise of political Islam through a leader and armed groups with jihadist ideological roots has concerned many in Syria’s Druze, Alawite, Christian and Kurdish communities.

Such concerns are not unfounded. The new government has announced changes to Syria’s school curriculum that some critics have described as giving an “Islamic slant to teaching”. And more recently, videos from Idlib province in 2015 have been shared on social media that show Syria’s new minister of justice, Shari al-Waisi, present at the execution of women accused of “corruption and prostitution”.

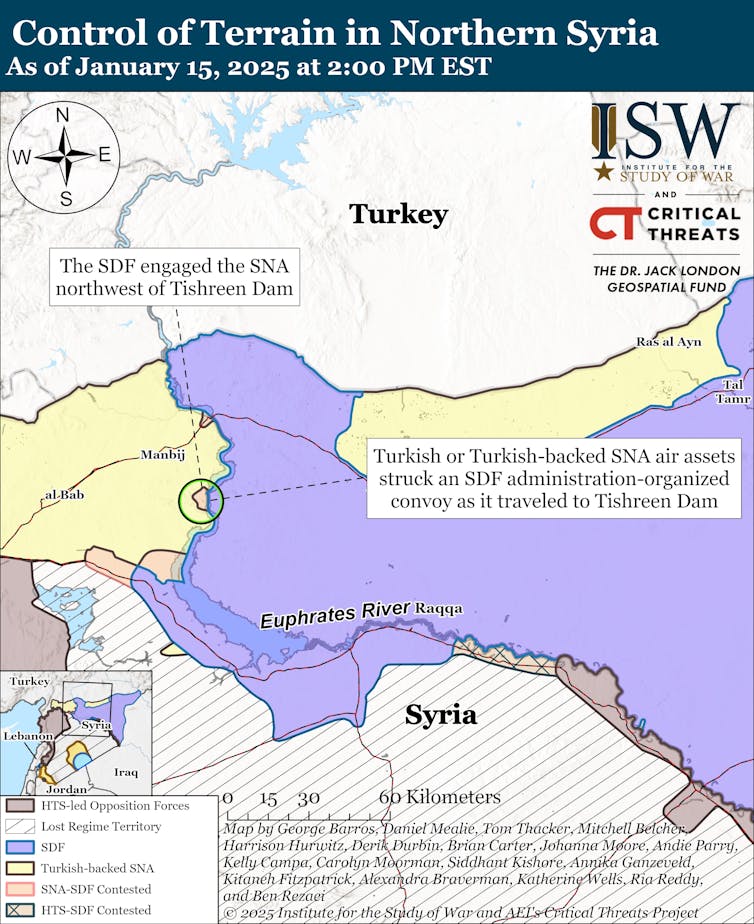

While al-Shara consolidates his authority in Damascus, armed conflict is escalating in northern Syria, particularly in Manbij and the outskirts of Kobane. The fighting is between the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) and several Kurdish militant groups, including the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

The SDF and SNA are clashing in northern Syria, particularly around the Tishreen Dam. Institute for the Study of War

One month ago, on December 17, the SDF general commander, Mazloum Abdi, took to social media to declare the group’s “steadfast commitment to achieving a comprehensive ceasefire throughout Syria”. He also wrote that the SDF was ready “to propose the establishment of a demilitarised zone in Kobane” to address Turkey’s security concerns over Kurdish militant groups operating near its borders.

Turkey, which sees these groups as extensions of the banned Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK), quickly rebuffed Abdi’s call and continued its military activities and build-up in the region. The Turkish defence ministry wrote on social media that they will “continue to take preventive and destructive” measures against what they call “terrorist organisations”.

Then, on December 30, the SDF held its first official talks with HTS. Before these talks, Abdi had claimed in an interview that the SDF did not seek to divide Syria and was “ready to play our part in building and participating in the government”.

However, he stressed that the group believes Syria “must be a decentralised, pluralistic and democratic state, where the country’s diverse identity is constitutionally protected”. Such a political model was established in 2013 in Rojava, an autonomous region in Syria’s north-east.

NEW -- *big* shift in optics from #SDF leader Mazloum Abdi, who for the first time, placed a #Syria revolutionary flag behind him during a new interview. pic.twitter.com/2qoPmpiEeV

— Charles Lister (@Charles_Lister) January 10, 2025

The central pillars of Rojava’s governance model are participatory democracy, ecology and gender equality. These principles are safeguarded in the Charter of the Social Contract of Rojava. However, conflict is making their implementation difficult.

Clashes near the Tishreen Dam on the Euphrates River have brought the dam to the verge of collapse. This has caused shortages of electricity and water in some areas of Rojava. The damage is also threatening agricultural production, which is key for food security in the region.

Ali Demir, the manager of the dam, has warned staff may not be able to hold back a rush of water that could result in a bursting of the Tabqa Dam further downstream. This would lead to significant environmental damage, even across the border in Iraq.

Women in Rojava have also expressed concern for the progress they have made towards democratic participation. These concerns are mainly due to HTS’s policies towards women in Idlib, where the group has governed since 2017.

These policies included strict enforcement of conservative dress codes, mobility restrictions, limited access to education and employment, and harsh punishment for dissenting women. No women held leadership positions during the group’s seven years of rule.

Sardar Aziz of the French Research Centre on Iraq, suggests that al-Shara “might prioritise services and development over human rights and democracy” as the political leader of Syria. Similar concerns have been raised by policy analyst Aaron Zelin of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who claims that “Jolani and his forces remain, at heart, an authoritarian armed group”.

Regardless, women in Rojava are determined to have a say in Syria’s future governance. In line with this goal, the Syrian Women’s Council has published a declaration calling on all political forces in Syria to ensure “equal participation of women and all the different religious, cultural and ethnic groups” in the future.

Prospects for peace

At the same time, Turkey maintains its opposition to any Kurdish autonomy in Syria. It did, however, allow a delegation from the pro-Kurdish People’s Party for Equality and Democracy (DEM) to visit Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the PKK, on December 27.

This marks the start of a new dialogue between Turkey and the PKK, following the breakdown of the previous peace process nearly one decade ago. The end of that process was followed by nine months of urban warfare in various Kurdish cities.

The conflict resulted in the deaths of thousands of people, including more than 1,000 civilians, the internal displacement of nearly half a million more, and the widespread destruction of Kurdish cities. The Rojava revolution played a crucial role in undermining the peace process, as it heightened the Turkish government’s perception of the Kurds as a strategic threat both domestically and over its borders.

The nature of this new process remains to be seen. Turkey’s focus seems to be the renunciation of terror and the dissolution of the PKK rather than on democratisation and peace. But the Kurds remain cautiously optimistic. In a written statement on December 30, DEM party delegates Pervin Buldan and Sırrı Süreyya Önder said they were “much more hopeful” about the new peace talks compared to previous processes.

More recently, on January 16, the SDF commander Abdi met Masoud Barzani, the former president of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. At this meeting, they agreed on pursuing a peaceful transition process with Damascus. Given Barzani’s close ties with Turkey, it is reasonable to suggest this meeting is also connected to the new process in Turkey.

It is no secret that the future of the Kurds in Syria is closely linked to the resolution of the Kurdish question in Turkey. What comes next for Syria, Turkey and the Kurds in the region will soon become more clear.

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings

Nasdaq Proposes Fast-Track Rule to Accelerate Index Inclusion for Major New Listings  Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters

Trump Allows Commercial Fishing in Protected New England Waters  Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify

Netanyahu to Meet Trump in Washington as Iran Nuclear Talks Intensify  Trump Signs “America First Arms Transfer Strategy” to Prioritize U.S. Weapons Sales

Trump Signs “America First Arms Transfer Strategy” to Prioritize U.S. Weapons Sales  Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate

Elon Musk’s Empire: SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI Merger Talks Spark Investor Debate  US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks

US Pushes Ukraine-Russia Peace Talks Before Summer Amid Escalating Attacks  Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue

Trump Says “Very Good Talks” Underway on Russia-Ukraine War as Peace Efforts Continue  Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links

Norway Opens Corruption Probe Into Former PM and Nobel Committee Chair Thorbjoern Jagland Over Epstein Links  Pentagon Ends Military Education Programs With Harvard University

Pentagon Ends Military Education Programs With Harvard University  JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand

JPMorgan Lifts Gold Price Forecast to $6,300 by End-2026 on Strong Central Bank and Investor Demand  Iran–U.S. Nuclear Talks in Oman Face Major Hurdles Amid Rising Regional Tensions

Iran–U.S. Nuclear Talks in Oman Face Major Hurdles Amid Rising Regional Tensions