The Bank of England was widely expected to slightly increase its official bank rate on November 4, but it decided to stick to the all-time low of 0.1%. However, the bank has made it clear that a rise will soon be needed, and the recent increases in mortgage rates indicate that lenders agree. So why the decision to hold off?

The Bank of England is well aware of the distress that higher rates cause for borrowers and, in particular, for the biggest borrower in the land: the UK government. At the current level of national debt, roughly £2 trillion, every rise in rates by one percentage point pushes up the interest paid by the government on its bonds by £20 billion per year over the long term.

Higher rates also have a dampening effect on the prices of property and financial assets such as shares. Indeed, this is one way in which monetary policy is believed to work: if people feel less wealthy, they spend less and this relieves the pressure on inflation.

On the other hand, what’s bad for borrowers is good for savers. As rates rise, bank deposits will be better rewarded and even the finances of our beleaguered pension funds should begin to look more healthy.

But regardless of who wins and who loses from higher interest rates, inflation is on the rise. The bank does not want to lose credibility by letting it rise too far before tightening monetary policy.

The inflation dilemma

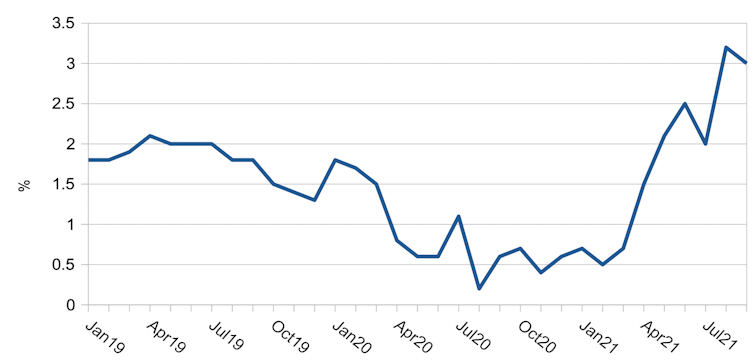

After rising for the past 12 months, UK inflation is currently 3.1%, and the bank expects it could even reach an uncomfortable 5% by early next year – much higher than its 2% target. Yet the bank maintains the view that this higher inflation will turn out to be temporary, arguing that it will fall back as the post-COVID excess demand for goods subsides and supply bottlenecks are worked out. Against that, energy prices are likely to remain higher, driven partly by climate initiatives; and if employers continue to have trouble filling vacancies, higher wages will also tend to push up prices.

The bottom line is that nobody really knows where inflation is heading, so the bank is wrestling with the usual dilemma: does it raise rates now to forestall future inflation, or does it hold rates down to avoid jeopardising the economic recovery while hoping that inflation will subside by itself? It can’t have it both ways.

Annual inflation 2019-21

This same dilemma is echoed in other countries. In the United States, the position is similarly troubling, with inflation already at 5.4% against a 2% target. Yet the Federal Reserve also continues to insist that the current high inflation is temporary, thereby justifying keeping its official interest rate (the Fed funds rate) near zero.

Yet the Fed is not completely sitting on its hands; it has announced that it will start “tapering” its quantitative easing (QE) programme, in which it is creating US$120 billion (£89 billion) a month to buy US government bonds and other financial assets to help prop up the economy. From the middle of November, it will scale this back by US$15 billion each month. This is at least an acknowledgement by the Fed that its excessively stimulatory monetary policy must eventually come to an end.

Back in the UK, the Bank of England has accumulated £800 billion of government debt as a result of its own QE asset purchases, designed to stimulate demand particularly since the outbreak of COVID. At some stage, the bank will need to begin offloading this debt.

Its choices of when and how to do this present the bank with arguably an even bigger dilemma than the bank rate, because unwinding QE will drive up yields on bonds – thus directly raising interest costs for the government and all other long-term borrowers.

Yields on 10-year UK government bonds

Trading Economics

In fact, yields have already started rising after many years of decline (see chart above). This is a sign that investors think that monetary policy needs to become tighter to curb inflation (by raising official rates and reversing QE) – which also explains why mortgage rates have already been rising.

This all confirms that the long era of ever-cheaper finance is finally over. The future will be tougher thanks to higher interest rates, or higher inflation, or both.

John Whittaker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

John Whittaker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  Gold and Silver Prices Rebound After Volatile Week Triggered by Fed Nomination

Gold and Silver Prices Rebound After Volatile Week Triggered by Fed Nomination  Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality

Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality  Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient

Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient  Russian Stocks End Mixed as MOEX Index Closes Flat Amid Commodity Strength

Russian Stocks End Mixed as MOEX Index Closes Flat Amid Commodity Strength  Asian Stocks Slip as Tech Rout Deepens, Japan Steadies Ahead of Election

Asian Stocks Slip as Tech Rout Deepens, Japan Steadies Ahead of Election  U.S. Stock Futures Slide as Tech Rout Deepens on Amazon Capex Shock

U.S. Stock Futures Slide as Tech Rout Deepens on Amazon Capex Shock  Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility

Dow Hits 50,000 as U.S. Stocks Stage Strong Rebound Amid AI Volatility  Bank of Japan Signals Readiness for Near-Term Rate Hike as Inflation Nears Target

Bank of Japan Signals Readiness for Near-Term Rate Hike as Inflation Nears Target  Dollar Steadies Ahead of ECB and BoE Decisions as Markets Turn Risk-Off

Dollar Steadies Ahead of ECB and BoE Decisions as Markets Turn Risk-Off  RBI Holds Repo Rate at 5.25% as India’s Growth Outlook Strengthens After U.S. Trade Deal

RBI Holds Repo Rate at 5.25% as India’s Growth Outlook Strengthens After U.S. Trade Deal  Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions

Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions  South Korea Assures U.S. on Trade Deal Commitments Amid Tariff Concerns

South Korea Assures U.S. on Trade Deal Commitments Amid Tariff Concerns  China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices

China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices  India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out

India–U.S. Interim Trade Pact Cuts Auto Tariffs but Leaves Tesla Out  Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure

Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure  South Korea’s Weak Won Struggles as Retail Investors Pour Money Into U.S. Stocks

South Korea’s Weak Won Struggles as Retail Investors Pour Money Into U.S. Stocks