Australia is in for a long and damaging economic slump, unless governments inject substantially more fiscal stimulus.

The July budget update forecast that unemployment would hit 9.25% in coming months.

The Treasury now apparently expects it to remain above 6% for the next half-decade.

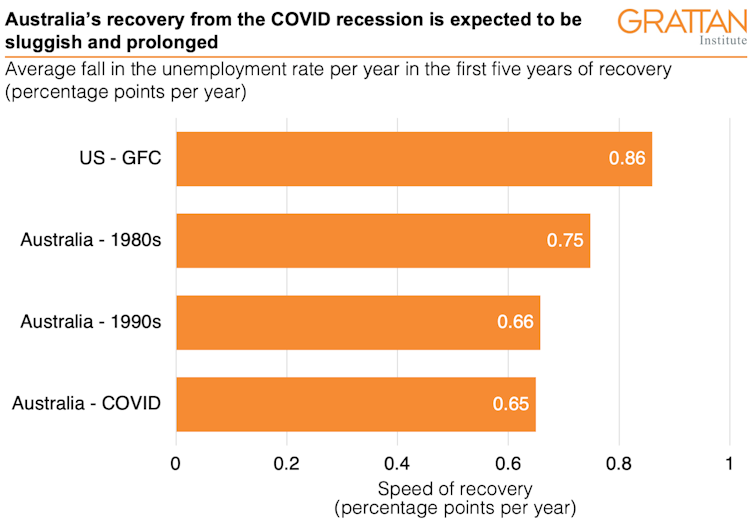

That would be a disastrously sluggish recovery – as slow as the recovery after the 1990s recession, now widely seen as a failure of economic management.

It would be a slower recovery in unemployment than Australia experienced after the 1980s recession, and also substantially slower than the US experienced after the global financial crisis, when unemployment took five years to fall from a peak of 10% to 5.7%.

The performance of the United States after the global financial crisis was no one’s idea of a rapid labour market recovery. Yet that’s what we are drifting towards.

Note: The ‘Australia — COVID’ number is based on a forecast 9.25% unemployment rate in late 2020 and a forecast 6% unemployment rate in 2025. Sources: OECD.Stat and Grattan calculations

A recession this long and deep would leave ugly scars.

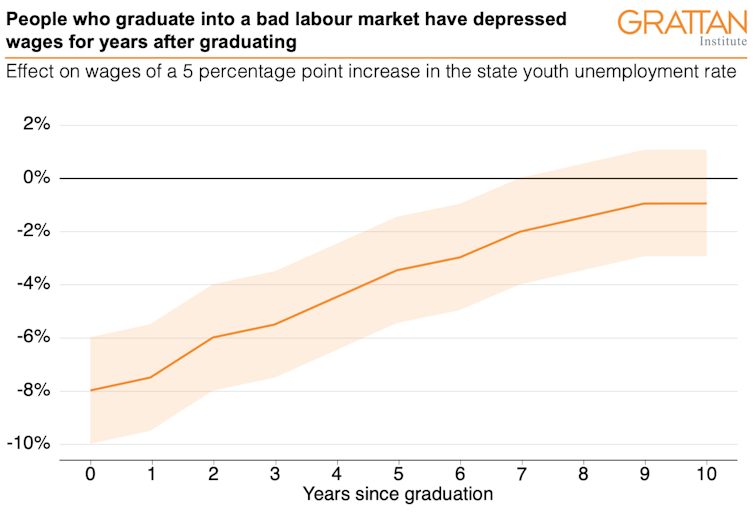

Recent work by officials at the Treasury found that when youth unemployment goes up by 5 percentage points, the wage that new graduates can expect to receive goes down by 8 percentage points, and they’re less likely to get jobs at all.

The effect on graduates’ wages lasts for years.

Over a decade they lose the equivalent of half a year’s salary compared to otherwise similar young people who graduated in more benign conditions.

Note: The shaded error is a two standard error confidence band. Source: Treasury Working Paper 2020-01

A Productivity Commission staff working paper came to a similar conclusion: economic downturns have big and long-lasting effects, particularly on young people unlucky enough to be entering the job market during and after them.

But the Treasury study finds the worst can be avoided if unemployment falls quickly.

For instance, if unemployment returns to pre-recession levels within three years, the hit to young workers’ wages over the following decade almost halves.

Getting unemployment down quickly will cost money

Faced with this scenario – a long and deep recession with sluggish recovery – governments ought to do everything in their power to stimulate the economy.

The Reserve Bank can and should do more, but by itself it can’t do enough. The Commonwealth government has to step up, spending what is needed.

It acted quickly and commendably to support households and businesses through the acute crisis period. Its actions weren’t perfect, but helped turn what was set to be an unprecedented catastrophe into something more like a conventional terrible recession.

But the spending taps look set to be turned off in the coming months, as the emergency support is withdrawn in accordance with a schedule approved by parliament last week.

The fall off the “fiscal cliff” might be cushioned a bit by the boost from households that have saved more during the shutdowns and households that have withdrawn their super savings, but right now the government looks set to be a drag on growth.

More – much more – government support is going to be needed over the months and years ahead.

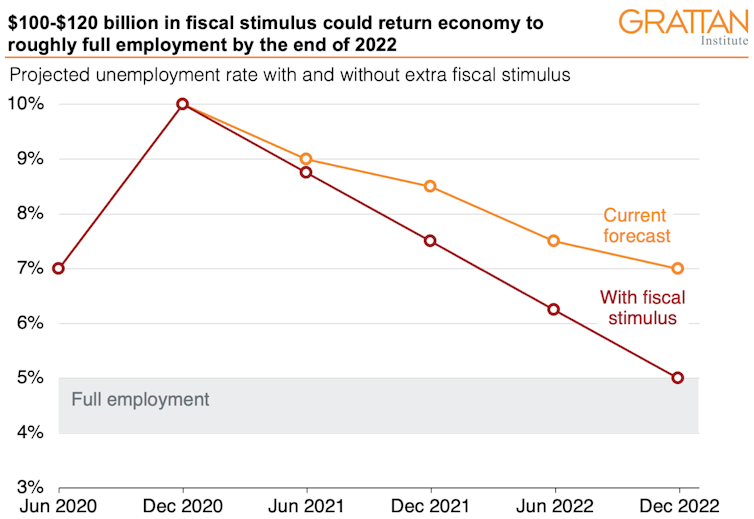

In June, the Grattan Institute called for additional fiscal stimulus of about $70-to-$90 billion over the next two years.

Those numbers now look too small.

Based on the updated Reserve Bank forecasts, we now estimate than an extra stimulus of $100-to-$120 billion will be needed.

RBA forecasts are linearly interpolated between six-month increments. Full employment estimate range represents one standard error band around central estimate of 4.5 per cent. Source: RBA (2020) Statement on Monetary Policy August 2020; Ellis, L. (2019), Watching the Invisibles, 2019 FreebairnLecture.

Our calculations suggest that would be enough to cut the unemployment rate by about two percentage points beyond where it would otherwise fall to by the end of 2022.

It would bring unemployment back down to around 5% rather than 7%.

Five per cent is around the level the Reserve Bank believes is needed to get wages growing again.

Australians should not settle for a prolonged slump, with the scarring and misery it would bring.

Our leaders should prepare a plan now to get unemployment down as quickly as possible.

The budget is due in four weeks, on October 6.

The Reserve Bank’s forecasts point to economic policy failure. It’s not too late to spend, and spend big, to avoid it.

Silver Prices Plunge in Asian Trade as Dollar Strength Triggers Fresh Precious Metals Sell-Off

Silver Prices Plunge in Asian Trade as Dollar Strength Triggers Fresh Precious Metals Sell-Off  Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality

Trump’s Inflation Claims Clash With Voters’ Cost-of-Living Reality  Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient

Singapore Budget 2026 Set for Fiscal Prudence as Growth Remains Resilient  South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom

South Africa Eyes ECB Repo Lines as Inflation Eases and Rate Cuts Loom  Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure

Oil Prices Slide on US-Iran Talks, Dollar Strength and Profit-Taking Pressure  Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal

Trump Lifts 25% Tariff on Indian Goods in Strategic U.S.–India Trade and Energy Deal  U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains

U.S.-India Trade Framework Signals Major Shift in Tariffs, Energy, and Supply Chains  U.S. Stock Futures Slide as Tech Rout Deepens on Amazon Capex Shock

U.S. Stock Futures Slide as Tech Rout Deepens on Amazon Capex Shock  Asian Stocks Slip as Tech Rout Deepens, Japan Steadies Ahead of Election

Asian Stocks Slip as Tech Rout Deepens, Japan Steadies Ahead of Election  China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices

China Extends Gold Buying Streak as Reserves Surge Despite Volatile Prices  South Korea’s Weak Won Struggles as Retail Investors Pour Money Into U.S. Stocks

South Korea’s Weak Won Struggles as Retail Investors Pour Money Into U.S. Stocks  Fed Governor Lisa Cook Warns Inflation Risks Remain as Rates Stay Steady

Fed Governor Lisa Cook Warns Inflation Risks Remain as Rates Stay Steady  Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns

Japanese Pharmaceutical Stocks Slide as TrumpRx.gov Launch Sparks Market Concerns  Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions

Trump Endorses Japan’s Sanae Takaichi Ahead of Crucial Election Amid Market and China Tensions  Gold and Silver Prices Rebound After Volatile Week Triggered by Fed Nomination

Gold and Silver Prices Rebound After Volatile Week Triggered by Fed Nomination  Dollar Steadies Ahead of ECB and BoE Decisions as Markets Turn Risk-Off

Dollar Steadies Ahead of ECB and BoE Decisions as Markets Turn Risk-Off  Vietnam’s Trade Surplus With US Jumps as Exports Surge and China Imports Hit Record

Vietnam’s Trade Surplus With US Jumps as Exports Surge and China Imports Hit Record